- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 42

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 42

“Was that your only choice?” he asks. “Marriage or war?”

“No. First I studied to become a novitiate. But I stopped short of taking my vows when I began working at the Arts Council and for my uncle at the Observatory and transcribing the sermons at New Park Street Chapel for the previous pastor. Then I met Coventry Patmore and helped him with his printing publications for the Museum, and so on and so forth. And through the Patmores, I began work at the Hospital for Sick Children, and through the hospital I met John Snow and helped him with some of his projects, and through him, I met Florence Nightingale. Thus began my nursing work with her at the Institute. You see, it all flowed from one to the other, the way life does outside the theatre.”

“From this you got Crimea?”

“Florence needs help. You have no idea how few women are willing to train as nurses to go with her abroad.”

“I have some idea, because most women aren’t mad.”

“I’m not mad, Mr. Cruz. Our soldiers need care, and I had nothing to keep me here. Have nothing,” she corrected herself. “Why would I not answer the call? I know Mummy is upset with me.”

“Everyone’s upset with you,” Julian says. Mirabelle is careless with everyone’s love because she couldn’t live how she wanted. “Are you going to the front to punish your mother?”

“Of course not, why would I want to punish my mother?”

“Okay,” he says in a clipped voice, his mouth twisting. “Is there anything else?”

She watches him. “You know, after I stopped performing,” she says softly, “I used to pray on rainy days for some other frisson to dust me with its magic. But it never happened.” She breaks off.

“Wounded and sick men are your idea of a frisson?” says Julian. Instead of healthy, hearty men?

“I’ll come back, Mr. Cruz,” she says. “I’m not going to the Crimea for the rest of my life.”

“You make it sound as if the rest of your life is infinite time.” Julian winces. “Do you remember the question you asked me in your dream?” Leaning on the oars, he droops like a sack of weeds. “Do you remember my answer?”

You have less than one silver moon.

“It was just a dream. I don’t put much stock in that.”

“But what if it wasn’t?” he says. “The war is going to last a few years. There will be a siege. There will be blood. What do you think happens to nurses when they treat infected patients year in and year out?”

Mirabelle tilts her head to gaze at Julian with sympathy. Is it sympathy? He’s not looking at her closely enough to divine.

“People can get sick anywhere,” she says. “You don’t think people get sick in London?”

And just like that, she has cut to the crux of Julian’s struggle. People can die anywhere. Los Angeles. London. Crimea.

“I’m either fated to live or fated not to,” Mirabelle says. “It’s in God’s hands, not mine. I have nothing to do with it.”

“But why deliberately put yourself in harm’s way?” Julian clenches his hands over the oars. He’d like to clench his hands over his ears. The lake shimmers around her. He can’t make her understand what he doesn’t understand himself—which way, which road, which path, which word, which act. Is there a right way? But if there isn’t, what is the fucking meaning of all life.

“Your family has been using me,” he says. “That’s why they’ve allowed me to be alone with you, to ride your horses and row your boats. They’re so desperate to have you stay, they’ve thrown their baby out with the bathwater. They’ve tried Charles, they’ve tried John Snow, others maybe. I’m their last resort. They would rather have you be publicly seduced by a Welsh pilgrim than get on that bloody train on September 20. Doesn’t that mean something to you, their desperation?” Dejectedly he lifts the oars and begins to row.

She raises her eyes. “Is it only their desperation?”

He stares back at her, full of love and woe. His arms are shaking even while he exerts force on the paddles.

“What about the other part of my dream?” she asks. “You have nothing to say about it? That you implored me to jump in a river?”

“Don’t be a skeptic, Miss Taylor,” Julian says. “There is a passageway under the Thames. The zero meridian transects the Royal Observatory, and it transects the river, too, to the Isle of Dogs and beyond. The meridian circles the globe and rises into the stars.”

“So what? And I’m not a skeptic.”

“Maybe instead of going to the Crimea on September 20, you should come to the river with me.”

“So you are asking me to jump in the river!” She laughs.

“Yes, because I’m a romantic,” Julian says. “I can’t help but wish, I can’t help but hope.” He takes a breath. “The tunnel comes to a dead end at a floodgate, a gate that controls the flow of water.” That is what Cleon told him. “I heard that the gate can open on September 20, perhaps during the sun flare at the Transit Circle.”

“Like a parting of the seas?”

“Like a path to the deepest channel of the Thames. We have about a minute before the floodgate closes. Maybe on the other side is…” Julian broke off. On the other side was what? A place where the waters didn’t turn to blood, where the fish weren’t slain, where there was no more darkness, or hailstones, or flames. What was on the other side if they crossed hand in hand and stayed steadfast?

“What’s on the other side?” she asks.

“Your life.”

“Under a river?” She is not persuaded. “In a raging current?”

“In the headwaters of your new self.”

She shakes her head. “That sounds romantic to you?”

“Better than war.” Julian stops rowing, reaches into his shirt, slips the rawhide rope over his head and places the entire necklace with the crystal, the rolled-up beret, and the two gold rings into her hands. “On the equinox, the crystal creates a flare when the sun hits it,” he says. “Come with me on September 20, and the mystery will be revealed to you, too.”

“You mean, it’s already been revealed to you?”

“Yes.”

“Just once?”

Julian doesn’t know how to answer her. “I keep being given a second chance,” is what he says at last.

And not just me, Mirabelle.

But our time is running out.

She glides the tips of her fingers over the crystal. “It’s giving me a slight shock,” she says, drawing her hand away. “I don’t like it. What are these gold bands?”

“Many years ago, I had them made,” he says. Eighty years ago. “I carry them with me.” He shields his eyes so she can’t look inside him. “There’s a beret, too. Would you like to see it? Here.” Carefully he unspools the soft hat from the rawhide wrapping, smooths it out, and hands it to her. He has taken good care of the beret over the years. It’s wrinkled, but not torn. She touches it uncertainly, examining the faded black stains on the leather. The intuition worries her forehead.

“It looks like blood,” she says. “It feels like blood.”

Julian doesn’t argue.

“Whose blood is it?”

When he says nothing, she drops the beret as if she’s burned by it.

His faith is like open water.

“I will repeat what I said in my dream,” Mirabelle says. “I’m not diving into the Thames with you, Julian. On September 20, I’m taking a train to Dover and a boat to Calais. I’m going to France. And then to the Crimea.” She pauses. “Unless…there is something you’d like to ask me. That doesn’t include jumping into sewers.” She waits. “Is there something you’d like to ask me?”

Julian is going to bite his lip to blood. “No,” he replies through his distorted mouth. He picks up the beret and rolls it back up into its thin red line, twining it with the rawhide rope.

“So, what are we talking about, then?” She is visibly disheartened.

“I want you to make the choice—to go or not to go—without my influence.” He slips

the necklace over his head and inside his shirt.

“But why?” Mirabelle exclaims. “We are influenced every day by a million things. Why would an informed choice be against my best interest? If your intentions are honorable, I must know that. And if they are dishonorable, shouldn’t I know that also?”

“Do you mean to suggest I have a choice in the quality of my intentions?” Julian says, striving for flippancy, but doesn’t answer the underlying question because he is made mute by the Gordian knot that constricts his windpipe.

And she doesn’t respond to his teasing, as she normally might. “Answer me, Mr. Cruz.”

What can Julian say but, “At the moment, I have no intentions, Miss Taylor.”

She exhales. He picks up the oars, and they stop speaking.

When they reach shore, she barely accepts his hand to help her out of the boat, nearly falling before she rights herself and storms to the horses.

“You don’t want to take a walk around the lake?” Julian asks.

“I most certainly do not.”

He has upset her. “Come on. It’s a beautiful day. Let’s…”

“Let’s ready the horses and head back, shall we?” She swirls to him. “But just so you understand—this is the last time you and I will be alone together.”

He bows his head. Hasn’t he been punished enough?

“This is the last time you will speak to me without someone else present.”

“Why are you being cruel?”

“Oh, listen to you, black pot!” she says. “This isn’t my doing. But now that you know I’m scheduled to depart the country in a few weeks, and now that you know why my family has been performing cartwheels in front of you—up to and including allowing you to be alone with me to motivate you—how do you think they’ll react when they realize you’re fully aware of what’s at stake and still choose to do nothing? You will be fortunate if the Metropolitan Police are not called to guard me from you.”

“One word from you…”

“Why would I give that word?” she cries. “To what purpose?” She pauses to compose herself. “Anyway, that’s one reason. And the second reason, even if I did deign to give a word as you glibly suggest, now that Prunella and Filippa know you’re staying with us at Vine Cottage, they will perpetrate a full-scale assault to prevent you from spending a minute alone with me. I guarantee they’re already at the house waiting for us to return. Prunella’s imperative is to find Pippa a husband. Nothing can or must or will stand in her way. The women will not tolerate our friendship or our professional relationship. They will accompany us on each of our daily labors, from the Observatory to the Institute. They will ride in our carriage. They will sit with us in the Museum stacks. We will never be alone again. I know that Pippa is counting the days until September 20 when I am gone, and she can have you to herself.” She watches Julian watching her. “So help me untie the horses, Mr. Cruz, and square your shoulders from the onslaught that awaits us.”

∞

The horses remain tied up. They continue to graze near the abundant willow under which the picnic blanket and basket have been spread out. Julian asks Mirabelle if she is hungry, and she says no. She collects daisies in the wet bog near the shore, makes a bouquet of them with some laurel and lilies. He paces the shoreline, thinking but not thinking, feeling but not feeling.

They are in a secluded cove of bush and tree, the lake lapping at their feet, the gently sloping hills around them, the birds chirping, not another soul in sight.

Holding her flowers, she steps in front of his pacing path.

“I don’t understand,” Mirabelle says. “On the one hand, sometimes you seem to be quite taken with me. And other times, you’re as distant as the moon. And sometimes, like now, it’s both at the same time.”

He can hear her breath rising and falling in her chest.

“Mr. Cruz…do you plan to answer me?”

But Julian is all about studying the pebbled sand.

“Will you please look at me.”

Julian shakes his head.

“Are you really not prepared to do anything to have me stay?”

“You mean there is something I can do to have you stay?” But he won’t raise his eyes to her! “You just told me there was nothing I could do. That you gave your word. You were going no matter what.”

“I suppose I wouldn’t mind having a true choice to make,” she says shyly.

The lake smells of backwater, overripe green, overripe red. It’s a warm August day. September is nearly here.

“All I’m asking is that you wait to make any decisions about the Crimea until after September 20,” Julian says. “That’s all. Just wait one more day.”

“And then?”

And then I will ask you everything. What you want of me, anything you want from me, I will do for you and give you. Yes will be my only answer. “I’m asking you to wait.” Wait one more day.

“Why?”

“I can’t tell you. And you don’t want to know. But you need to trust me.”

“Do you want me to go to Scutari?”

Julian cannot say.

“Do you want me to stay in London?”

Julian cannot say.

“Is there anything you want from me now?”

Julian won’t move his head, won’t look up, won’t even breathe, for the breath will give him away.

“Why is it so hard to ask for my hand!” she exclaims.

“Not before September 21.” How absurd he is! How foolish, how idiotic, how spellbound.

He descends onto the trunk of a tree that has fallen in the water. She perches near him. Taking the bouquet out of her hands and setting it between them, Julian presses his mouth into the center of her soft white palms, kissing one and then the other. “Mirabelle…” he whispers, lowering his forehead into her hands.

“Julian…can you please look at me?”

He shakes his head, but she has electrified him with those three little syllables and her magnetizing proximity, sitting too close in her flowing dress, her curled hair falling down, her riding boots against his dusty own.

“Come on. Look at me.”

With difficulty he raises his eyes to her.

“Don’t you want to kiss me?” she whispers.

He nearly groans. “There’s nothing I want more.” How can one heart hold so much love next to so much fear? “But I’m afraid if I kiss you, you will die.”

She cocks her head. “Are you speaking metaphorically?”

“No.”

“Will your kiss be so overpowering that it will cause me to cease breathing?” She mines his fallen face for clues, for humor.

“No.”

“Well, what say you, O Julian Cruz of Bangor?” says Mirabelle. “Is your kiss worth it?”

Beat. Blink. One shallow breath. “No.”

They stare at each other. He doesn’t look away. And neither does she.

She remains pensive. “Color me intrigued,” she says, her hands in his.

“Don’t get on that train. Just wait.”

“How can a girl live out her life without at least half-endeavoring to uncover the truth about this magic kiss of yours?”

“You’re not listening to me. Do not endeavor, by half or any other way.”

“It’s just a kiss, Mr. Cruz, just a kiss…” she whispers, tugging on his hands, inclining her body to him, her head tilting, her mouth parting.

Julian leans forward and kisses her. Passion and heartbreak are in his open kiss.

A flushed breathless Mirabelle wrenches herself away from him and stands up.

“Where are you going?” Julian says, also standing up, raising his pleading hands.

“I’d like to go swimming,” she announces. “The water might cool me off.”

Julian doesn’t think it will. “Did you bring a swimming suit?”

“I don’t know about Wales, Mr. Cruz, but here in London, the swimming suit is a dress. It comes down to my knees and buttons to

my chin. It has long sleeves. And a belt. It comes with a cap. And I must wear pantaloons under it. I might as well jump into the water in the dress I’m wearing.” She takes a step toward him.

And he a step back. He can’t kill her with his love again. No matter how desperately he wants to. “Miss Taylor,” he says, not trusting his voice. It’s thick like it’s gained weight. “Please—let’s untie the horses and leave.”

“Oh, the horses are untied, Mr. Cruz. The horses are galloping.”

“No, let’s ride back home. Would you like me to help you into the saddle?”

“What I’d like,” says Mirabelle, “is for you to help me out of my dress.”

“No. I beg you.”

“No?”

“No…” Julian whispers. There isn’t a man in London, past, present, and future, who means it less. She stands in front of him stunning, ephemeral. Inside her perfect body is her heart, is her soul, is paradise. But Julian can’t touch her until she is loosed from hell, until she’s been freed to flee to another dimension, a dimension in which she will live, and only then will earth be divine. Because she will be on it.

She takes off her bonnet and pulls the pins and ribbons from her wavy hair. The dark tresses fall down below her shoulders.

“Don’t do that,” he says hoarsely.

“Do what?” She starts to unbutton her sleeves.

“That,” he says. “Please.” His hands are up in surrender.

“I don’t know what you mean,” she says, untying her bodice. “Summer is going to be over soon. I would like to take a dip in my lake before spending the winter in the Crimea. Is that wrong?” She kicks off her boots. “Would you like to come in with me, cool off? You seem quite warm yourself.”

All of him is on fire.

She half-turns her back to him. “Could you help me unlace my dress?”

He doesn’t move.

“You won’t help me? Fine,” she says. “I’ll do it myself.” Little by little she loosens the strands that hold the crinoline to her body. Finally, she steps out of the whalebone rings, leaving the dress and petticoat like a tent by the tree, and stands in a long ivory silk chemise, draping down to her ankles. Underneath the silk, she is naked. A distraught Julian backs away. There she is. Open your eyes and behold. And cast your lot into her pot.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

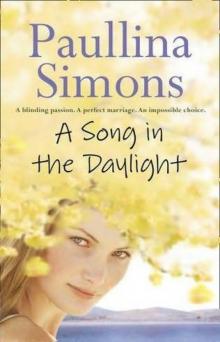

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)