- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 41

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 41

“Nothing is outside it,” the learned man says.

“Oh, come now, George,” Spurgeon says. “Surely, something is outside it?” Charles proceeds to tell the story of when he was a boy of ten, and a priest spoke to him of a vision he’d had of Charles preaching to a great multitude of people. Charles was stunned by this, as he had been a child severely hampered by shyness. “But the power of this positive suggestion transformed me,” Spurgeon says. “It was an anomaly in every sense of the word. Who knows if what the priest had seen was true. But the mere suggestion that this was even possible made the thing itself come true.”

“On the equinox,” Julian says, “a portal opens in the balance between earth and heaven. A portal that allows mystery to flow out.”

“Julian is right,” Spurgeon says. “The sun flare is merely an observable reflection of some real but invisible mystery. George, don’t tell me nothing like that has happened to you.”

“Only when I met my wife,” George Airy replies, exchanging a look with Julian.

“I hope someday to meet a woman who makes me feel like that,” Charles says.

“Speaking of which,” Filippa says, “do you know who’s coming to our ball, pastor? Susannah Thompson, the daughter of Abner Thompson, the local ribbon-maker. You remember her, don’t you? She and Mirabelle used to be close.”

“We still are,” Mirabelle says. “She’s a wonderful girl, Charles. And she is quite taken with you.”

“Ah, yes.” Spurgeon looks down into his port, suddenly uncomfortable. “Well, I look forward to seeing her there.”

“You’re coming to our soiree, too, Mr. Cruz, aren’t you?” Filippa asks Julian from across the table, her eyes darting from Mirabelle to him as they sit next to each other, palming their drinks. “It’s a week from tonight. It’s for an excellent cause. It’s to raise money for the hospital in Scutari.”

“Scutari?” Julian repeats absentmindedly.

“Yes, the Scutari Hospital in Constantinople,” Filippa says. “For Florence and Mirabelle and their team of nurses. Charles, what are you going to do in a few weeks when Mirabelle is gone? Mummy and I don’t know how you’ll manage without her.”

A hush falls over the table. Julian stops tapping his glass, stops being absentminded. He looks up, glances at the anxious, weary faces, turns to his left and peers at Mirabelle. He feels as if he’s misheard, skipped a word or two in the discussion and is now struggling to catch up. “Where is Mirabelle going?”

Aubrey jumps up, knocking over her wine glass, and asks if anyone would like more sardines and artichokes.

“To Constantinople, of course,” Filippa replies. “To tend to British soldiers in the Crimean War. Miri, you didn’t tell him? How could you not tell him? You haven’t stopped talking about it for months. I’m sorry to be the first with the news, Mr. Cruz,” Filippa adds. “You and Mirabelle are so friendly and I hear you’ve been spending so much time together. I was sure she would’ve told you.”

George Airy shakes his head. Charles Spurgeon folds his hands. John Taylor stiffens his spine, but it’s Aubrey’s face that affects Julian most of all. She looks so angry. “Hush, Pippa! Why are you always sticking your nose where it doesn’t belong!”

“And where’s that, Mrs. Taylor?” Filippa says. “I was just making conversation.”

At the eye of the storm sits Mirabelle, her hands in her lap, her shoulders squared. She doesn’t smile, she doesn’t frown. She says nothing. Certainly, she doesn’t look at Julian.

“Yes,” Charles says, in a resigned voice. “I’m afraid it’s true. Mirabelle and Florence are traveling to Paris and from there, they and their twenty nursing companions are taking the train across Europe to Turkey.”

“Your friend is Florence Nightingale?” Julian says to Mirabelle. “The lady with the lamp?”

“I’ve never heard her called that, but yes,” she replies.

“When do you leave? Wait, don’t tell me”—Julian knows the answer even before she speaks—“is it September 20?”

“Yes—how—how did you know?”

“Lucky guess.” He cannot look at her.

“I kept telling you, Julian,” George Airy says, “in our material world, time is of the utmost essence.”

Julian keels like a bottomed-out boat, lists as if he’s been shot in his side.

“Are you all right, Mr. Cruz?” Filippa asks cheerily. “You’ve gone all pale.”

Trying to steady himself, Julian pushes away his chair and rises from the table. “Will you excuse me, please,” he says. “I’m feeling a bit under the weather.”

Upstairs he keeps his balcony doors closed so he doesn’t hear their voices down below.

He barely sleeps that night.

Crimea. September 20. Leaving. Halfway across the world.

Crimea is a bloodbath. And worse, the wounded soldiers are housed in deplorable infested conditions.

Leaving.

Does he let her go or does he try to stop her? As if he even can. Her parents couldn’t. Charles Spurgeon couldn’t. Her work couldn’t. John Snow’s proposal of marriage couldn’t. Julian wonders how Snow is progressing in his cholera research. The British soldiers in the Crimea could use his help. They’re about to fall from the disease. Not some of them. All of them.

Does he go with her? As if he even can. He has no papers, no documents, no identity, no correct sex. He is not a nurse or a woman.

Does he disappear as he first wanted to, vanish until September 20, leave her to her fate? To show how much he cares, does he turn his back on her? To show his love, does he abandon her? Not forever, like Ashton’s father abandoned Ashton’s mother, just for a little while.

Does he talk to her, persuade her?

And persuade her to do what exactly, leave or stay? Is London Mirabelle’s destiny, or is it Scutari? Is she safe if she doesn’t meet him at Coffee Plus Food, if she finds a ship to Italy, if she doesn’t walk into the Great Fire, if she sails to the Americas? Which way doom, which way salvation?

Superficially London seems safer. But only on the surface. London is a cauldron of death, Julian knows that. London has never been safe.

Does he confess, tell her everything? Can a woman live knowing the date of her own death? Julian knows it, and he can barely live. What does he do as a sentient being to keep her from her fate? London or Scutari? Which way is human, which way is moral, which way is good? And is his choice different because the heart of his heart beats for her? Does love make the choice possible—or impossible?

War?

Or peace?

To ask for her hand, or to wait until after September 20?

And what if, just like before, there is no after September 20?

Oh God! Help me. Help me.

To save her does he do nothing—or everything?

Julian finally understands. This is why the soothsayers are in the eighth circle of hell, only one ring above the traitors. As punishment for the dark arts, the divinators must walk forever backwards, their heads twisting around to see where they’re going, their tears falling down their backs as they cry. They use forbidden means to reveal what man is not supposed to know.

Julian finally understands. Foreknowledge—even paltry, impoverished, feeble—takes away his free will. It takes away his power to act, to do, to seek, to feel.

Foreknowledge takes away the life man desperately craves.

As it has taken away Julian’s.

Even with his gift of partial sight, even having lived through what he has lived through, Julian cannot act. He can’t reach for her hand, can’t touch her face, can’t kiss her. Nor can he stay away, can’t turn his back on her, can’t wait it out. He can’t let her go, and he can’t come near her. Which way does she bend to be safe, away from the wind or with it?

And the worst thing of all, the most dreadful, most unbearable thing of all: Does it even matter?

Will anything matter in the fate of her mortal life?

What if there is n

o fate beyond the fates? What if there never was, and never will be, what if that’s the truth Julian refuses to learn?

He wishes for terrible ignorance.

Terrible knowledge is worse.

Julian spends a shivering night walking backwards, his head twisting around to see which way he is headed, tears falling down his back as he cries.

∞

Sunday morning, polite but silent with one another, he and Mirabelle head to church to hear Charles Spurgeon. In the back they stand, listening to his roar. “No sooner is Love born than she finds herself at war,” the pastor cries. “Everything is against her! The world is full of envy, hate, and ill-will. The seed of the serpent is at war with all that is kind and tender and self-sacrificing, for these three are all marks of a woman’s seed. The dark prince of the power of nothing leads the way, and the fallen spirits eagerly follow him, like bloodhounds behind their leader. These evil spirits create dissension and malice and oppression among women and men. What a battle is yours, you, the soldier of Love! What a crusade against hate and evil! Do not shrink from the fray. As a lily among thorns, so is Love among the sons of men. Cannon to the right of you. Cannon to the left. Yes, horse and hero fall. But you arise from the jaws of death and the mouth of hell. So, forward the light brigades, forward. When does your glory fade? Never.” Julian and Mirabelle don’t look at each other.

After the sermon, they approach Spurgeon in the vestry. He studies them with sad, sober eyes. Even his considerable oratorical gifts fail him. “We all told you it was time to make a decision,” he whispers to Julian after Mirabelle has boarded the carriage. “You refused to listen.”

“I didn’t refuse,” Julian says. “But what if you knew things that made that decision impossible? What then?”

“What could you possibly know?”

“Things I wish to God I didn’t.”

Back at Vine Cottage, they saddle their horses and ride out quietly to the lake, Mirabelle sitting side-saddle, still in her voluminous Sunday dress, falling in tulle and chiffon layers around the mare. She asks Julian to go on a boat ride. It’s warm and sunny and the air is still. She sits in front of him, her light blue skirts billowing, a wide-brim hat covering her loosely bound coffee-colored hair. He tries not to look at her as he rows.

“Are you upset with me, Mr. Cruz?”

“No.”

“But you’re not speaking to me.”

“I’m contemplating the universe.” He forces out a grimace. “I’m concentrating on rowing.”

She chews her lip. “I apologize for not saying anything to you about Paris.”

“Do you mean the Crimean War, Miss Taylor? Because that’s really the important part, I feel.”

“Yes. That’s what I meant.”

“The less said about it, the better.”

“I want to explain why I didn’t tell you.”

“I know why,” Julian says. “You didn’t want me to talk you out of it. Filippa was quite clear. Everyone’s been trying to talk you out of it for months. And you’re sick of it.” His gaze is fixed on a line of weeping willows to the left of her head. “I know I would be. Once I set my mind to do something, the last thing I want is a stream of naysayers. You didn’t want me to be one of them. You preferred not to sully our friendship. That’s fine. You don’t owe me an explanation.” Will you just listen to him. He’s become a stoic, an ascetic fatalist.

Mirabelle sits watching him row. The muscles in his face are constricted. He pants slightly from the exertion in his arms and chest.

“We were friends,” she says. “We are friends. I should have told you.”

Now it’s his turn to twist his lip. He fights with himself to stay quiet.

A silent moment goes by. Julian’s life goes by.

“One thing though…” How quickly he loses that battle. It’s a knockout in the first. “Were you ever planning to tell me? Or were you just going to hop on a train on September 20 and be off? Perhaps you were planning to leave me a note? Or have your mother speak to me on your behalf? She’s been talking to me on your behalf for weeks.”

“Not on my behalf, most certainly.” Mirabelle leans back. “But that’s more like it, Mr. Cruz. For a minute there, I thought you weren’t human.”

“Whatever I am,” Julian says, “I’d still like an answer to my question. The more beautiful the woman, the more honest she should be, don’t you think?”

Briefly Mirabelle loses her composure. “I apologize. I was going to tell you—of course I was. I was waiting for—for the right time.”

“Ah. Before or after September 20?”

“Mr. Cruz, pardon me for asking, but do you have an interest in my comings and goings besides an academic one?” She falters. “Despite several entreaties, you have not made your intentions clear to my pastor or to my parents, or frankly even to me.”

“Really,” Julian says. “You feel as if I haven’t made my intentions clear—even to you?”

For a weighty moment, their eyes catch. She looks away in shame. “What I mean is, you have been very proper,” she says quietly.

“You would’ve liked me to be less proper?”

“Perhaps…slightly less proper, yes.”

“To what end?”

“I don’t know what you mean.”

“My impropriety, would it have a point? Would it be to keep you in London? Or…” Julian levels his locked and loaded gaze on her. “Are you interested in impropriety strictly for its own sake?”

The blunt question agitates Mirabelle. She twitches, folds and refolds her body, fiddles with her skirts, her lace, her nails. Either she doesn’t have an answer, or she doesn’t want to say. Which means that Julian’s question hit the point too directly on the head. Is that why she’s been presenting her open lips to him? Because she wanted a fleeting improper interlude before her real life began? “Mr. Cruz…look, there’s nothing to be done about it now. I promised Florence.”

“It’s a very good thing, then, that I haven’t been improper with you, Miss Taylor,” Julian says, furiously rowing, “because I might have erroneously construed your allowing me to be improper with you as a promise to me, a promise you obviously never intended to keep.”

“Couldn’t keep, not didn’t intend to.”

“Same difference.”

“No, it isn’t.”

“It is, Mirabelle!”

She sucks in her breath—either from his raised voice or from her name on his lips, both a first.

“Why are we talking about this pointless thing?” Julian says, forcing himself to lower his voice. “What’s there to say about it? You gave your word to Florence, and in a few weeks, you’re leaving for the front. You didn’t tell me, but now I know, and you said you were sorry, and I accepted your apology. It’s done. Let’s change the subject.”

Her arms stretch out to him in supplication. “Please listen to me,” she says. “Can you stop rowing?”

“No, I want to get back.”

“Please. I want to tell you something.”

Reluctantly Julian raises the dripping oars out of the water. The gliding boat slows to a stop. He and Mirabelle bob in the middle of the summer lake. Looking into the bottom of the boat at her feet, he sits in the middle seat, leaning slightly forward, still clenching the oars, his elbows on his knees. She sits across from him, her hands clenched in her lap.

“When I was younger I wanted to be on the stage,” Mirabelle says. “That’s all I ever wanted.” She watches his face for a reaction. “That doesn’t surprise you?”

“Not in the slightest. You are theatrical down to your fingertips.”

“I am not!” she exclaims and then sighs. “Well, fine. But my parents, my friends, our pastor all told me it was madness. No young lady with a hope of marrying well could ever be in such a profession.”

“Perhaps you should’ve settled for marrying badly.”

“That’s what I told them! They wouldn’t listen. My father was an esteemed solicitor

and clock-maker. My mother was a respected music teacher. You know what it took for them to have me. In the end, no matter what I wanted, I couldn’t dishonor them.” Disappointment distorts Mirabelle’s comely face. “The last time I took the stage, seven years ago, I was the Lady of the Camellias. Oh, I was excellent. You should’ve seen me. Now they’ve set it to music, made an opera out of it.”

“Yes. Verdi composed it. La Traviata.” That was the opera that once upon a time Julian wanted to see in New York with Gwen instead of The Invention of Love. Placido Domingo was Armand. On the lake with Mirabelle, in Sydenham, Kent, in 1854, Julian remembers it.

“But even before Verdi,” she says, “Dumas’s story was grand! So tragic, full of shattering love. I received three curtain calls.” She smiles at the memory, then becomes bleak again. “I wasn’t allowed to be what I wanted to be. Prunella told my mother my performances were overtly sexual. She said that continuing to be on stage would infect me with a bothersome carnal appetite.”

Julian peers at her through his half-hooded eyes.

Mirabelle blushes at his gaze. “The theatre wasn’t serious enough. It wasn’t worthy. Well, fine. They wanted serious, I would give them serious. I said I would attend university. They had nearly the same reaction to that as they had to my desire for the stage. My mother told me I would be disparaged as a bluestocking. My father told me women could not attend university. It made women unmanageable. He said I was already plenty unmanageable. And Prunella told me that too much study could have a harmful effect on my ovaries. If I went to university, even if later I did manage to snare a foolhardy sop, I might never be able to give him children. They suggested music instead, singing, drawing. Needlepoint. Perhaps some light gardening. They wanted me married, birthing babies, and sewing. I wasn’t having that nonsense. We all know how that’s turning out for Emily Patmore.”

So now Julian knows: Mirabelle lives but not to her satisfaction. That expression on her face when he first met her was of a woman trapped, afraid that life was passing her by, and affecting an air of indifference to her own imprisonment.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

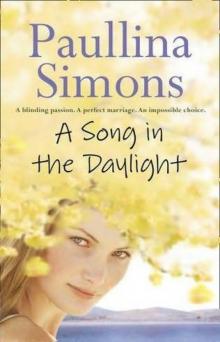

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)