- Home

- Paullina Simons

Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty Read online

PAULLINA SIMONS

Children of Liberty

To my good friend Nick,

without whom this book, and many things,

might never have been

The world was all before them, where to choose

Their place of rest

John Milton

Each of us Inevitable;

Each of us Limitless—

Walt Whitman

Table of Contents

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Part One: The Barber’s Daughter

Chapter One: Daughter of the Revolution

Chapter Two: Sons of Liberty

Chapter Three: North End

Chapter Four: Great Expectations

Chapter Five: Summer Street

Chapter Six: A Sunday in a Small Town

Chapter Seven: Immigrants, Debutantes, Students

Chapter Eight: The Rewards of Mission Work

Part Two: The Objection Maker

Chapter Nine: The Natives and the Pilgrims

Chapter Ten: In the Boston Winter

Chapter Eleven: The Quarry

Chapter Twelve: Tulips

Part Three: Earth's Holocaust

Chapter Thirteen: Minstrel Songs

Chapter Fourteen: The High Priestess of Anarchy

Chapter Fifteen: On their Knees by the Sea

Chapter Sixteen: Violet Catastrophe

Chapter Seventeen: The Marble Faun

Chapter Eighteen: Earth’s Holocaust

About the Author

By the same author

Copyright

About the Publisher

Part One

THE BARBER’S DAUGHTER

Love—what is love? A great and aching heart;

Wrung hands; and silence; and a long despair

Robert Louis Stevenson

Chapter One

DAUGHTER OF THE REVOLUTION

THERE had been a fire at Ellis Island the year before Gina came to America with her mother and brother in 1899, and so instead of arriving at the Port of New York, they had set sail into the Port of Boston.

Salvo had been in a bad mood since the day they left Napoli. He had left his sweetheart behind—the girl wouldn’t part with her family. This, among other things, soured him on his. He refused to stay with the girl he loved, but resented his family for his own choice. “As if Mimoo and Gina could go to America by themselves,” he scoffed.

“We don’t have to go, Salvo,” his mother said, and meant it.

“Mimoo!” cried Gina. “What would Papa say?”

“Papa, Papa. Well, where is he, if he is so clever?”

It was summer and Gina wished for a cloudless day. She stood at port on tiptoe and gaped at the sky, wishing for a view of what they had been sailing to for weeks: a city line across the wide open bay to show them the glimpse of a life that was just around the corner. Stretching up she squinted straight into the July fog, her palm in salute to focus her sights on what she had imagined was urban beauty: sprawling metropolis bustling, smokestacks billowing, ships to and fro, civilization. But she could see nothing beyond the thick slate mist and oppressive melancholy. “Ahoy, Salvo!” she called, despite the lack of sight. “Come see!”

Salvo did not come see. Like a sack he sat behind her on the main deck and smoked, his arm around his black-clad mother. They had just lost their father. Five of them had been planning to go to America for seven years, but Gina’s oldest brother had been killed in a knife fight six months ago. A drunken mob had run amok, Antonio had got caught in the middle, there was a struggle with the police, people trampled by horses. It wasn’t a military knife that had taken him, but a hunting knife. Like it mattered—Antonio was still dead.

And less than three months later Papa’s heart stopped.

Papa had wanted to go when the children were still small, but Mimoo refused. She wouldn’t go without money. Imagine! Going to America, starting a new life with nothing. Assurdo! She wasn’t going to come to America a village pauper. But we are village paupers, Mimoo, the great Alessandro had said. He didn’t argue further, there was no point. Gina’s mother declared that when she came to America, she would walk in on her own two feet, not crawl in with her hand outstretched. Papa agreed with that, but then he died.

Some of the money the Attavianos had saved went for Alessandro’s funeral. But Mimoo had promised her husband she would go to America no matter what, and so, a month after he was buried, they borrowed just enough for three steerage beds. When Gina said borrowed, she meant stole: her mother’s older sister took the money from the kitchen lock box of their blind father, putting a note inside which he couldn’t read, saying that the “debt” would be repaid when Mimoo and her children got on their feet in the new land.

Salvo, the middle child, had told Gina, the baby, that Massachusetts Bay, emptying into Boston Harbor, was almost as wide as the ocean that fed it. A vast expanse of water flowed in from three corners of the globe, peppered with flat, green, rocky islands. Lighthouses stretched up from the rocks. Gina was eager to see these lighthouses, these islands. “That’s the problem, Gina,” Salvo said. “You can’t. Lighthouses are supposed to be beacons to guide your way? You can’t see them either in this fog. That’s how it always is. Can’t see nothing until the rocks you’re about to crash into are already upon you. Much like life.”

Frowning, Gina stepped away from her brother and he looked self-satisfied, as if that was exactly what he wanted. She watched the water, wondering what instruments you needed to navigate waters you couldn’t see ten feet in front of, if instruments like that even existed. Please don’t let us crash against the rocks when we are so close. Was that likely?

“If you can’t see where you’re going? I’d say more than likely.” Salvo smirked. He was a maestro smirker. He had an elastic face, ideal for grimaces and sneers. His condescension was so irksome.

She walked from the stern to the bridge to talk to the second in command who was standing like a monument at the bow, peering through a telescope. What impressive concentration. She told him what her brother had said, and asked him to deny it.

“He is right.”

“So how does the ship not crash?”

The adjutant showed her. On the map in the blue, black oval marks were circled in red. “We try to avoid those.”

“How?”

“By navigating away from danger. We have a map.” He tapped on it impatiently.

She left. “What if you don’t know where the danger is?” she called to him. “What if you don’t have a map?”

“Well, you wouldn’t set out on a voyage without knowing where you’re going, would you?” he called back to her, young and smart-alecky.

The ship seemed to stay on course due straight, though it was hard to tell. The bay below looked the same as the sky above, like granite. There was a whipping wind, and the waters were choppy.

Gina’s mother started throwing up again. The journey had been relatively uneventful except for the vomiting. Mimoo’s stomach couldn’t endure what Salvo and Gina bore with no problem. It’s hard to be old, Gina thought, bringing her mother a fresh towel, a new paper bag. Yet Mimoo was so brave, at nearly forty-five heading west into the possibilities no one could see.

“It’s unseemly for you to be this excited,” Salvo said to Gina, watching her skip across the gun deck, inhaling the ocean air.

“It’s unseemly for you not to be excited,” she replied. “The sails are set and filled with wind, Salvo! Why did we even set off with your attitude?”

“Why indeed,” Salvo muttered.

“It’s what Papa wanted. You want to go against the will of your father?”

“It isn�

��t what we planned,” her brother said.

Gina didn’t want to admit to grumpy Salvo that her own excitement waned when she couldn’t see where she was going. She had imagined it differently—there was going to be abundant sun, twinkling lights, perhaps a sunset over the skyline, tall buildings to welcome her, a dramatic invitation into the new life, an arduous voyage that ended with a landscape full of color. She hadn’t expected gray fog.

She remained on deck at the railing, looking for a sign, hoping for a sign.

Just like Papa had dreamed, his remaining children would build a different life in the awe-inspiring vast land. While Mimoo pinched pennies, Papa taught his children to read so they wouldn’t be illiterates. And then he taught his children English. If only Papa hadn’t gone and died. Never mind. Gina could read, and she could speak a little English. Her wavy hair was getting tangled standing on the windward side of the open waters. Mimoo had ordered her to tie it back up, but there was something undeniably appealing in the image of herself in a light blue dress, standing like a reed with her long, tanned arms like stalks on the rails, her espresso hair flying in the drizzle and mist, all against the backdrop of steel gray. If only someone could paint a picture of her searching for America while the wind was wild in her hair. It pleased her to draw this picture in her mind. Sure, we might crash against the rocks like Salvo predicted, but this is how I’m going to stand in my last minutes, proud and unafraid.

Gina didn’t really believe they would crash. She believed she was immortal, like all the young.

Eventually she got cold and went back to sit with her family. Like three sacks they sat huddled, their hands folded on their knees, her mother holding the rosary beads, worrying them between her fingers, her mouth mutely moving over the words of “Ave Maria” and the invocations of God. Mary, pierced with the sword of sorrow … Maria, trafitto dalla spada del dolore. Her mother said that loudly enough for Gina to hear, so she could respond with pregate per noi. But Gina was not in a praying mood. So she tutted under her breath, saying nothing, and her mother tutted, not under her breath, and moved closer to Salvo who took his mother’s hand and echoed, pray for us.

“Do you think she is grieving, Salvo?” Mimoo asked about Gina, though Gina was sitting right there and could hear.

“Of course, Mimoo. She just hides it. She grieves where we can’t see.”

“Impossible!” exclaimed Mimoo. “When you mourn, everyone knows. You can’t keep such secrets.”

After a short glare across their mother at Gina, Salvo kept pointedly quiet. Gina knew that Salvo knew his sister could indeed keep secrets. She hid her first crush (no easy feat in a town where everyone knew everyone else). Hid her tasting too much wine at the Feast of the Holy Theotokos. Hid not going to confession every week. Made a big show of pretending to go, then didn’t. Was that in itself a sin? Hid her terrible grades. Even hid not knowing English as well as her father believed she did. Pretended she knew it better!

All the things Gina had to keep to herself, she kept to herself. Like her anxiety now. She was worried about the stark contrast between the anticipation of their sun-filled arrival and the ocean of blindness the ship was actually navigating through. She went to find the co-captain again.

“How far do you think we are?” she asked.

He pointed. It was like pointing at the wheel he was holding. “The docks are less than a kilometer away. What, you can’t see?”

When she ran to tell her brother and mother they were almost at land, they didn’t believe her. They were right not to, for the ship took another two hours to reach the shore. She could have swum faster! She was going out of her mind with impatience and boredom.

“Where’s the fire?” Salvo demanded. “Where are you planning to rush off to? What do you think will happen when you walk ashore? What, you think your whole life is going to change the minute you step off this boat?”

Gina had thought so a week earlier, somewhere near Iceland. But into his imperious expression, she said, “Don’t be so negative, Salvo. No nice American girl is going to want you when you get like this.”

“Who said I want an American girl?” He swore, then quickly apologized to Mimoo. He was usually such a good sport about things. Nothing could get Salvo down for long. His good looks and cheerful disposition assured him of finding comfort when he needed it. This late afternoon, they stood shoulder to shoulder at the masthead, watching the dockhands tie up the boat. Though she was four years younger and a girl, they were nearly the same height, Gina and Salvo. Gina was actually taller. No one could figure out where she got the height; her parents and brothers were not tall. Look, the villagers would say. Two piccolo brothers and a di altezza sister. Oh, that’s because we have different fathers, Gina would reply dryly. Salvo would smack her upside the head when he heard her say this. Think what you’re saying about our mother, he would scold, crossing himself and her at her impudence.

Chapter Two

SONS OF LIBERTY

MIMOO disembarked on Gina’s arm. Salvo pushed their three trunks on a dolly, bobbing down the plank. Gina was wobbly herself from being so long at sea.

They passed through the health control tent before they were allowed to step foot onto solid ground. No leaky eyes, no unexplained rashes, no single women traveling alone, all papers in order. Slowly they dragged their steamer trunks behind them.

“I don’t feel so good,” Mimoo said. “Where are we?”

Gina looked around for a sign. “Some place called the Long Wharf. Or Freedom Docks,” she said pointing. Her hair was hidden in a respectable bun as Mimoo had ordered.

“You’re just excited, Mimoo,” Salvo said. “Sit. Get your bearings.”

“You are a fool, Salvatore,” his mother said.

“I am not!”

Mimoo was a stout, solid woman dressed from her gray head to flat toe in widow’s black. “I haven’t kept anything down for six weeks. I am not remotely excited.”

They all sat down for a rest on a low wall near the water. So many people had left the boat before them that all the benches by the waterside had been taken by other families. The mother prayed, the brother and sister wiped their brows, glanced at each other. Where to now? Where to get some water? It was loud and chaotic; a swarm of seagulls flapped overhead, anticipating food.

“Señora! Señor! Señorita!” A sturdy male voice sounded to the right of them. Turning toward the tenor they were confronted with two young men, beaming and American, the taller one carrying a jug of water and bread, the other one a wicker basket with shiny red apples and half-moon oddities with thick yellow skin.

“Señora!” the shorter, friendlier of the two exclaimed again. He took off his skimmer hat and bowed to them, turning to face Gina. When he straightened out, he smiled widely at her, his brown eyes locked in. He seemed like the most genial of young men. He was open of face, effusive, extroverted. “You look tired and thirsty, please, let us help you, we have water.” Putting down his basket, he deftly grabbed the jug from his mate and poured water into a small metal cup, handing it to the sitting Mimoo. “Here, drink, señora. We have a little bread. Harry, offer them some. Would you like to try a banana?” He lifted his basket to show Gina. “They’re an extraordinary delicacy from the southern Americas, soon to be available all over the world.” Gina wanted the apple, but it would have been messy to eat. She didn’t want juice running down her chin as she was trying to look lady-like. Salvo, not caring about his chin juices, grabbed the apple. No one eyed the bananas with anything but rank distrust.

“I’m Ben Shaw,” the amiable man said to her. “Absolutely delighted to make your acquaintance.” He smiled.

The quiet taller boy stepped forward. “Would you like some bread? Or just the water?” He was rumple-haired and wiry, but wore a smart suit with a vest and tie, though the starched white shirt was coming loose from the trousers and the silk tie was askew. One of his gold cufflinks was about to fall off. Gina’s father would’ve liked him—he wasn’t boi

sterous. He had clever, serious eyes. Gina decided he was shy, which she found instantly appealing. He watched her calmly, not friendly, but not unfriendly either. She smiled at him—nothing timid about her—showing him her white Italian teeth, her gleaming unsubdued eyes, her flushed face. “I’ll take some bread, please,” she said in English. “Hello.” She stuck out her hand. “I’m Gina.”

“I’m Harold,” he said, leaning forward, extending his. “Harry. Pleased to meet—”

But before he could finish, or touch her, Salvo stepped between them, his back to his sister. “I’m Salvatore Attaviano,” he said, shaking Harry’s hand. “Gina’s older brother.” She had no choice but to retreat, tutting with frustration, and pinching her ridicolo brother hard between his shoulder blades.

“I’d like some bread, Salvo,” she said with irritation. “Would that be all right?”

Salvo broke off a piece from Harry’s loaf and handed it to her. She grabbed it from him. “This is our mother, Maria,” he told the two men. “But everyone calls her Mimoo.”

“Even her children?” Ben smiled.

“Especially her children,” Gina said, moving this way and that.

Ben brought some bread to Mimoo. “Where are you headed?” he asked. “Can Harry and I help you, take you somewhere? We have a carriage waiting.”

Mimoo nodded vigorously from her sitting position on the wall. “I can’t walk, my ankles are swollen. Salvo, tell him a ride would be most welcome.”

“We need to get to a train station,” Salvo said. “We are going to Lawrence.”

“Lawrence!” Ben exclaimed. “Whatever for?”

Gina began to speak, to explain the significance of Lawrence, but Salvo cut her off. “That is where we are going. What is it to you?”

Ben shrugged, unprovoked. “It’s nothing to me,” he said. “E niente. Just trying to, um, aiutare.” They bickered in two broken languages.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

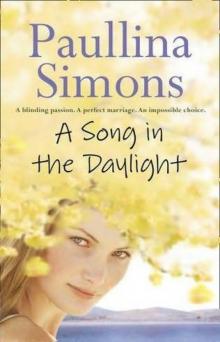

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)