- Home

- Paullina Simons

The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Read online

Dedication

For Tania, my last child, the joy of my life

Epigraph

A safe fairytale is not true to either world.

J.R.R. Tolkien

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue: The Transit Circle

Part One: The Ghost of God and Dreams

1. The Invention of Love

2. Book Soup

3. Lonely Hearts

4. Gift of the Magi

5. Normandie Avenue

6. Gwen

7. Ashton and Riley

8. The Red Beret, Take One

9. Phantasmagoria in Two

10. Griddle Cafe

11. Duende

12. The Four of Them

13. Pandora’s Box

14. Shame Toast

15. Charlie’s Dead

16. Fields of Asphodel

17. A Rose by Any Other Name

18. Lilikoi

19. Mystique

Part Two: The Tiger Catcher

20. Klonopin

21. The Apothecary

22. Waterloo

23. White Crow

24. The Question

25. The Widow’s Daughter

26. Great Eastern Road

27. Red Beret, Take Two

28. When We Were Kings

29. Zero Meridian

30. Notting Hill

31. Time Over Matter

32. A Boy Called Wart

33. Dumbshow

Part Three: Medea

34. Moongate

35. White Lava

36. Black River

37. Dead Queen, Take One

38. Chandlery

39. Medea

40. Lady Mary

41. The Italian Merchant

42. Fynnesbyrie Fields Forever

43. The Boy and the Boatman

44. Josephine and the Flying Machine

45. Sebastian

46. Consequences of Happiness

47. The Coat

48. Side Effects of Electrocution

49. The Lady, or the Tiger

Author’s Note

An Excerpt from A Beggar’s Kingdom

Real Artifacts from Imaginary Places

About the Author

Also by Paullina Simons

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

The Transit Circle

I SHOULD HAVE KISSED YOU. JULIAN LAY NAKED ON HIS BED, clutching the red beret, staring at the ceiling. I should have kissed you the last time I saw you.

After half a night passed like this, he gave up on sleep, jumped up and began to get ready. He had a lot to do to be in Greenwich by noon. Don’t dawdle, the cook told him. You have very little time. You have a picosecond inside of a minute. And don’t get stuck. Where you’re going, the opening is wide enough for one man, but not for all men.

And what was Julian’s wise response to this?

“How long is a picosecond?”

“One-trillionth of a second,” the exasperated cook replied.

Julian dressed in black layers. He shaved. He slicked back his unruly brown hair and tied it up so it didn’t look like what it was—a bushy mane on a man who long ago stopped giving a damn. Julian was square-faced, square-jawed, straight-browed, granite-chinned, once. His hazel eyes looked gray today, huge, sunken into his gaunt cheeks, the dark bags under his eyes like somebody clocked him, the full mouth pale. He had lost so much weight, he had to punch a new notch in his belt; his jacket could’ve fit two Julians inside.

It took him a while to get out; he kept forgetting this, that. At the last minute, he remembered to text his mother and Ashton. Nothing too alarming—like I’m sorry—but still, he wanted to leave them with something. Jokes to make them think the old Julian wasn’t too far away. To his mom: “I used to feel like a guy trapped in a woman’s body. Then I was born.” To Ashton: “You can’t lose a homing pigeon, Ash. If your homing pigeon doesn’t come back, what you’ve lost is a pigeon.” But he did leave a separate note for Ashton on his dresser.

As instructed, Julian left his cell phone at the flat, his wallet, his pens, his notebooks. He left his life behind, including the words he had written just yesterday called “Tiger Claws.”

What do you ask of life

At night the world you can’t change

desire drunkenness rage

Flies by

While you lie flat on your back

Under claws and lizards

In the purple fields.

He brought four things: a fifty-pound note, an Oyster fare card for the tube, the crystal on a rope around his neck, and the red beret in his pocket.

At Boots at Liverpool Street, he bought a flashlight. The cook said he would need one. And then the trains were slow like he was slow. Julian waited forever for a change at Bank. At Island Gardens, he looked down into his hands. They had been clenched since Shadwell. Lately he’d been staggering, foundering, drowning. Without time, his wandering life had filled up with nothing but watery impressions, his days were without architecture, without frame or matter, a muddle, a madness, a dream.

But not anymore. Now he had purpose. Lunatic, foolish purpose, but hey, he was grateful something was being offered to him instead of nothing.

In Greenwich, the flat landscaped park below the Royal Observatory is lined with crisscrossing paths called Lovers’ Walks. Deep inside the park, on top of a steep hill with a wild garden, for centuries the British astronomers have studied the skies. Today, on a blustery day in March the garden was nothing but bare branches whipping about, blocking the view of what Julian was climbing to the top of the mountain to find.

He felt idiotic. Did he buy a ticket? Did he loiter until the appointed hour? The cook told him to find a telescope called the Transit Circle, but the Observatory was home to so many. Where was this enchanted spot where all impossible things became possible? Julian caught himself scoffing and felt ashamed. His mother taught him better than that, told him never to mock the thing you were about to fall on your knees in front of.

“Which way to the Transit Circle?” Julian asked the cashier behind the table.

The pretty girl smoothed out her hair. “George Airy’s Transit Circle? Right through there. I can take you, if you like. Will it be just one ticket for you?” She smiled.

“Yes,” he said. “And no, that’s fine, I’ll find it. Do you sell pocket watches?”

“Yes, in our gift shop. Do you need a compass, too? Maybe a tour guide?” She tilted her head.

“No, thank you.” He wouldn’t look up, wouldn’t meet her gaze.

With the girl hovering nearby, Julian bought a watch in an unopened box. She wanted to test it to make sure it worked, but he said no. He didn’t want her touching it, imprinting his brand-new timekeeper with her own spirit.

“You won’t be able to return it if something’s wrong with it,” she said.

“That’s all right,” he said. “I’m not coming back this way.” Whatever happened, he wouldn’t be coming back.

“That’s a shame.” She smiled. “Where are you going?” When he didn’t answer, she shrugged, a friendly girl marking time. “Look around,” she said. “Take your time.”

Julian had almost nothing left from his fifty. He hid the remaining pound coins in a souvenir vase along with his Oyster card. Was that wrong, to hedge his bets? No, he decided. Even people who sought out miracles were allowed to be cautious. That was him—a cautious man seeking out a miracle. He had some time to kill so he wandered around killing it. It was only eleven o’clock. He tried to remember all the things the cook told him, but there had be

en so many. “At noon, the sun will pass through a pinhole in the glass crosshairs overhead,” the cook said. “A beam of light will strike the quartz in your hands. The blue chasm will open. You must hurry. The rest of your life awaits.”

It sounds difficult and complicated, Julian said. The cook stepped back from the grill and judged him up and down, a cleaver in his hands. “You think this part is complicated? Do you have any idea what you’re about to do?”

No. Julian had no idea. He knew what he had been doing. Lately, nothing. But way back when, he did things, like mark time with his baby down the road from his Hollywood dreams. Sun beating down on palm trees and lovers, Volvos parked in secluded corners. Windows open. Joy flying in, like wind. Julian wasn’t a skeptic then. Well, like he always said, there was a time for everything.

“Where’s the Prime Meridian?” Julian asked a gruff older guard inside one of the rooms in the pavilion.

“You’re on it, mate,” the guard replied. His name tag said Sweeney. He pointed to an enormous black telescope. “You’re in the Transit Room. And that’s the Transit Circle, right on the meridian line.” Over nine feet long, Airy’s telescope looked like a field gun aimed at the stars. It was flanked by a set of glossy black stairs, their base set into a square well slightly below the main floor.

Through the open door, pale sunlight. The brass line marking 0.0 longitude was riveted into the cobblestones in the courtyard. Julian watched the tourists hamming it up on the line, one foot in the east, one foot in the west, standing on each other’s shoulders, taking pictures, posing, laughing. He checked his new watch.

11:45.

His hands trembled. To steady himself, he grabbed the low iron railing that separated him from the telescope, the retractable roof open, the patchy sky above him.

He was so utterly alone.

A strange, vast, rainy, foreign city. London like another country unto itself. Julian glanced back at the guard. The portly man sat on a stool, an elbow on the wood table, indifferent to Julian, as was the whole universe. There was a window behind Sweeney, a glimpse of taupe leafless trees blowing about in the sharp wind. It had been so gusty in London the last few days, like an eyewall of a hurricane passing through.

11:56.

Reaching into his shirt, Julian pulled out the stone that hung on a leather rope around his neck. Leaving it in its silver webbing, he laid it into his shaking hand. In the gray light, the crystal didn’t sparkle or shimmer. Silent and cool, it lay in his open palm. Once the stone had been in her hands. There was sun then, a sparkling mist of dreamlike bliss, the beginning, not the end—or so he thought.

Was this the end?

Or was it the beginning?

“The crystal oscillates a million times a second,” the cook told him—a cook, a magician, a warlock, a wizard. “And you oscillate with it. You are the oscillator. You are the chain reaction, the chemical ignition, the voltage soaring through your own life. Go, Julian. The time has come for you to act.”

There is no other time.

Until the end of time.

Running out of time.

11:59.

Julian gripped the crystal. His vision blurred. The memory of pain is what causes the fear of death. The heart grows numb. There’s a sense of suffocation. As the lungs become paralyzed, the heart cannot breathe.

So it is with the memory of love.

O my soul and all that’s within me, the beggar cried, raising his palm to the sky.

Ladies and gentlemen, it’s showtime!

In the picosecond before the clock struck noon, in the blink he still had between what was and what was yet to be, Julian asked himself what he was most afraid of.

That the inexpressible thing being offered to him was possible?

Or that it wasn’t?

There’ll be another time for you and me.

There’ll never be another time for you and me.

As the sun moved into the crosshairs at noon, he knew. He would do anything, sacrifice everything to see her again.

Help me.

Please.

I should’ve kissed you.

Part One

The Ghost of God and Dreams

“Like a ghost she glimmers on to me. And all thy heart lies open unto me.”

Alfred, Lord Tennyson

“I love acting. It is so much more real than life.”

Oscar Wilde

1

The Invention of Love

“I’M DEAD, THEN. GOOD.” THOSE WERE THE FIRST WORDS SHE said to him.

Julian and Ashton flew to New York from L.A. with their girlfriends Gwen and Riley to see the star-studded adaptation of Tom Stoppard’s The Invention of Love off Broadway. The play—with Nicole Kidman in the starring role!—about the life and death of British poet A.E. Housman, originally written for men, had been reimagined and restaged with all women, except for the part of Moses Jackson, Housman’s objet d’amour, which was played by some male newcomer, who was “ominous like a powder keg,” the New York Times had reverentially written.

At first, when Gwen had suggested going, Julian balked. He knew something about The Invention of Love. His unfinished masters, a papercut inside him, included Stoppard’s play as part of the assignment.

“Oh, you think you know something about everything, Jules,” Gwen said. She was always dragging him to cultural things. “But you don’t know about this. Trust me. It’s going to be fantastic.”

“Gwen, if we’re going all the way to New York, why don’t we see La Traviata at Lincoln Center instead?” Julian said. He wasn’t particularly a friend of the opera, but Placido Domingo was Armand. That was worth a cross-country trip.

“Did you not hear when I said Nicole Kidman is A.E. Housman? And Kyra Sedgwick is her sidekick!”

“I heard, I heard,” Julian said. “Is Ashton going to agree to this?”

“He will if you will. And what, you think Ashton would rather see Placido? Ha. We have to expand his horizons. And clearly not just his. Come on, Jules, don’t sulk, it’ll be fun. I promise.” Gwen smiled toothily as if her promises were stone-carved.

They made a weekend out of it. Ashton hung up his favorite sign on the door of his store: GONE FISHING (though he didn’t fish). The four of them like the musketeers often traveled together, spent weekends down in Cabo or up in Napa. They flew into JFK on Friday, had dinner at La Bernardin, where Ashton knew the owner (of course he did), and they got to eat for free. Afterward, they met up with a few friends from UCLA, went drinking in Soho and dancing in Harlem.

Hungover and slow, they spent Saturday afternoon at MOMA, did some window shopping on Fifth Avenue. When Saturday night rolled around, Julian was almost too tired to go out again. He had bought a fascinating little book at the MOMA gift store, The Oracle Book: Answers to Life’s Questions, and would have liked to order room service and leaf through it—looking for answers as the book suggested. He had opened it randomly to two provocative replies, answers to questions he wasn’t asking.

One: You’ve drawn the seven of cups. Is this what you really want?

What was this referring to in that sentence?

And two: A solar eclipse hints of an unexpected ending.

What ending was he expecting?

Dressed for a Saturday night on the town—the men in dark jeans, fitted shirts, and structured blazers; the girls made up and blown out, in high heels and open necklines—they had pre-theatre sushi at Nobu in TriBeCa, all but Riley because it was B day and Riley didn’t eat on B days, and cabbed it to the Cherry Lane Theatre in Greenwich Village.

And wouldn’t you know it, Nicole Kidman had an understudy!

The sign on the board read: “Tonight, the part of A.E. Housman will be played by Ms. Kidman’s understudy, Josephine Collins.”

A loud unhappy hullaballoo rippled through the ticketholders. It was a Saturday night! Why would the star of the show be out without a word? “Did she fall down the stairs? Did she catch a contagious disease?” Gwen asked

. No one knew. The box office was mum. The social media was quiet. Since the only name above the title of the play on the marquee was Tom Stoppard’s, refunds were out of the question.

Julian thought his girlfriend was going to have a polar icecap meltdown right on the pavement. Gwen was upset at the poor woman at the ticket window, as if Nicole’s absence was the woman’s fault. “But why is she out?” Gwen kept repeating. “Can’t you tell me? Why?”

Julian tried to make it better. Giving Gwen a small commiserating pat as they took their seats, he said, “Josephine Collins is a good stage name, don’t you think?”

Gwen glared at him. “You never say anything to actually make me feel better when I’m upset,” she said. “Like you don’t even care.”

Julian glanced at Ashton on his right. His friend was chatting with Riley, chuckling over some private joke, their blond heads together.

He tried again. “You did amazing, Gwen, really. These seats are incredible.” And they were. Third row center.

“Oh yes, they’re excellent,” Gwen said. “All the better to see the understudy from.”

Ashton elbowed him. “I keep telling you, Jules, in some situations, it’s best to shut the hell up. This most definitely is one of them.”

Julian stared straight ahead. After an interminable minute, the red curtain rose.

The understudy stood center stage in the footlights.

“I’m dead, then. Good,” she said to him, and swiveled her hips.

A slouching, heavy-lidded Julian sat up in his seat.

The play may have been fine. It may have been terrible. Gwen spent the moments during applause and the intermission in a ceaseless harangue against the understudy, so it was hard for Julian to form a coherent opinion about the play.

But he formed an opinion about the understudy.

The accidental girl was in front of Julian for over two unsuppressed hours.

She was remarkable. Though she was young and played an old man looking back on his life and finding it wanting, she brought melancholy and elegance to the stage, she brought wit and pain and outrage. She brought it all. Everything she had was left on the stage in front of Julian.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

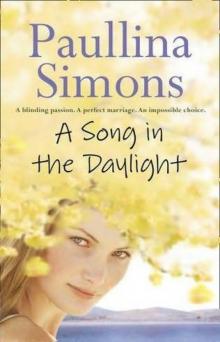

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)