- Home

- Paullina Simons

Bellagrand

Bellagrand Read online

Dedication

For my mother,

An engineer

A teacher

An immigrant

A romantic

A dreamer

A giver of life

Who looked for Paradise

Every place she lived.

Epigraph

But heard are the Voices

Heard are the Sages,

The Worlds and the Ages:

Choose well; your choice is

Brief, and yet endless.

—Johann von Goethe

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Part One

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part Two

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Part Three

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Chapter 19

Chapter 20

Chapter 21

Epilogue

About the Author

By the same author

Back Ad

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Prologue

1936

ON A TRAIN A once beautiful woman sits shivering in an old coat. Next to her is a young man nearly at full bloom. He doesn’t shiver. He stares straight ahead, stone cold, his face inscrutable. So is the woman’s. Except for her shivering, neither of them moves. She wants to speak but has nothing to say. She glances at him. He has nothing to say either.

Their ride is long. Eight hundred kilometers. Five hundred miles through bleakest terrain. The rivers hardly move, the melting ice crushing down the flow, the waters heavy. The flattened fields are black, old speckled snow clinging to the trees gray and bare. It’s grim, desolate, barren, and it’s all flying by. O World! O Life! O Time! On whose last steps I climb.

The young man stares out the window purposefully, single-mindedly. A boy yet not a boy. His hair is black upon his head, his eyes the color of coffee. He wants nothing less than to discuss the unspeakable. The train car is almost empty. They deliberately took the train, the one no one takes, because it gets in late at night. They don’t want to be noticed.

The woman tries to take his hand. It’s cold. He gives it, yet doesn’t give it. He wants to be left alone. He wants to shout things he knows he can’t, say things he knows he can’t. He stops himself only because of her, because of his reverence for her—still and despite everything. The things he wants to whisper, she is not strong enough to hear and doesn’t deserve to. How could you bring me here, he wants to ask her in his most frightened voice. Knowing my life was at stake, how could you come here with me? It’s too late now for if onlys. Why didn’t you know enough back then?

Listen to me, she whispers intensely after the train screeches to a stop and the few remaining passengers shuffle out. There’s nothing to be done. You can’t think about what’s past.

What else is there to think about? The future?

I want you to not look back. Forget where you came from. Forget everything, do you hear?

That’s the opposite of what you’ve been telling me my whole life.

The train speeds on.

It’s a long way between two metropolitan cities. They have ample time to sit, to stare speechlessly at the countryside.

He wants to know about only one thing. He wants to ask about the place he can’t remember. She refuses to entertain his questions, hence her new commandment: stop looking back. His entire life, he has heard only: never forget where you came from. Suddenly she wants him to forget.

He asks her about the place he forgot. To help him remember what he can’t remember.

Stop asking me about what’s meaningless, she says.

The past is now meaningless? Why can’t you answer me?

Why do you keep wanting to know? What does it matter? God, you’ve been on and on about it lately. Why?

Why can’t you answer me?

She turns to him. Promise to remember about the money?

You just told me to forget everything. So that’s what I’m going to do.

Remember only the money. Make sure you hide it again. Keep it secure. But don’t forget where it is. Don’t keep it in the house in case they come, but hide it somewhere close to you, somewhere safe, where you can easily get to it. Do you have such a place? If you don’t, you’ll need to find one.

The money! The money is what makes him want to rail at her more, not less. The money is the thing that brings cold to his heart, and cold toward her. The money is what screams to him the brutal truth: You did know what you were doing when you brought me here. That’s why you saved the money, took it with you, hid it, kept it hidden all these years. Because you knew. You can’t claim ignorance, which is what I want to believe in most of all, your ignorance of the way things might turn out for us. Turn out for me. But you keep reminding me about the money. Which reminds me that this act on your part—bringing me here—was for my destruction.

He says nothing.

Do you hear me?

I’m trying desperately not to.

Promise me you’ll remember.

I thought you just told me to forget? Make up your mind.

It’s not about the money.

You want me to remember it’s not about the money?

Stop joking.

Who’s joking? After what happened today, how do you think your money will help me?

Here not much, you’re right. But elsewhere it might buy you another life. It might free you. It’s not magic. You must participate in your own salvation. Strength. Resoluteness. Courage. Will they be the hallmarks of your character? I don’t know. She shrugs her crumpled narrowing shoulders. I hope so.

He shrugs his widening ones. Perhaps instead I can misspend it. Drink it away, maybe? He stares—glares—at her. Buy myself fancy shoes and red wool overcoats?

Where are you going to get those here? she asks.

Anything is possible with money. You just said.

Please don’t jest. This isn’t the time.

They whisper under the relentless hum of the wheels, under the hiss of the steam engine.

Tell me about that place, he says. Tell me or I’ll promise you nothing.

I know nothing about it.

The warm white place with the boats and the frogs. The carnival wheel across the blue water. What am I remembering?

I don’t know, she says, letting go of his hand, falling back against the seat. A nightmare perhaps.

He shakes his head.

She closes her eyes.

Promise me you’ll find a way to keep the money safe, she repeats in a breath. Everything else, including the marble palace with the white curtains, will one day be revealed.

Not today?

Nothing is clear today and won’t be for a long time.

They sit so close. He is slumped down, deep in the crook of her arm. He turns his face to her, away from the icy window. Tell me honestly, do you think we’ll be okay? His tremulous voice is too small for his body. Or do you think because of what we did we might be in danger?

She meets his eyes, a beat, another, a blink, and then she smiles. No, she says. We’ll be fine. She kisses his forehead, his hair, his face. Don’t worry. Everything is going to be all right. They sit with their heads pressed together.

Ti voglio bene, she says. You are what I love most in life.

N

ow maybe. Once you loved someone else too.

Yes, my son, and still do, she says, her voice trailing off, the marsh grasses outside, the taupe and gray towns flying by. Klin, Kalashnikovo, Okulovka, Luka. Once another Calais lay on my heart. Once I loved more than just one someone.

Sic transit gloria mundi, she whispers. Thus passes the glory of the world.

Part One

BREAD AND ROSES

1911–1918

If you press me to say why I loved him,

I can say no more than because he was he,

and I was I.

—Michel de Montaigne

Love is not blind;

that is the last thing that it is.

Love is bound;

And the more it is bound

The less it is blind.

—G. K. Chesterton

Chapter 1

WINE INTO STONES

One

ALL LOVE STORIES END. Who said that? Gina heard it once years ago. But she didn’t believe it. That hers never would is what she believed.

Gina set her internal clock by two things. One was the train schedule to Boston, a shining city on a hill if ever there was one. And the other was her monthly cycle. She’d been marking the calendar for the last three years. She’d been making the trip to Boston for twelve, and she was making it still, setting store by it, anticipating it. She would put her long-fingered hands in black silk gloves on the train window to touch the towns she passed and would dream about other cities and cradles, parks and prams, annual fairs and lullabies.

Her gauzy reflection in the glass returned curls and dark auburn hair, hastily piled up because she was always late, always running out of time. Returned translucent skin, full lips, bottomless coffee pools for eyes. Her rust-colored wool skirt and taupe blouse were not new but were clean and pressed and perfectly tailored, a custom fit for her tall, slender, slightly curvy figure. She always made sure, no matter how broke they were, that whenever she went out she was dressed as if she could run into her high-society father-in-law and not look like an immigrant, could run into her husband’s ditched and furious former fiancée and not look like steerage, could run into the King of England himself and curtsy like a lady.

Where else besides Boston might the train take her? If she stayed on past North Station, where might she ride to? Where would she want to ride to in her velvet hat and leather shoes? If the train could take her anywhere, where would it be? She spent Monday mornings imagining where she might ride to.

Every Monday but today.

Everything was different today, and was going to be different from now on. Everything had changed.

Gina was running down Salem Street past the lunchtime peddlers, breathing through her mouth to avoid the pervasive odor of the North End—fish and molasses—that today was making her subtly queasy. The train had been delayed and she knew her brother would be upset because until she arrived to look after his little girl, he couldn’t go to work.

By the time she got to his cold-water flat, all the way in the upper-north corner of Charter and Snow Hill, he was fit to be tied, pacing about the tiny living room like a caged lion, carrying Mary, who was cooing merrily. She clearly thought it was all in good fun, daddy carrying her back and forth, back and forth, rocking her in his arms as if he were a swing.

“I’m sorry,” Gina said, extending her arms to the child. Salvo had dressed her, but like a dad would. Not only did nothing match, but he had dressed the child in shorts—in December.

He didn’t want to hear it. “You’re always sorry.” He swung the baby upside down. She squealed more more and then cried when he handed her over. Not to be outdone, Gina held the girl upside down by her ankles. Mary chortled, and this allowed Gina to speak.

“I have to talk to you, Salvo.”

“You’ve made that impossible. Should’ve thought of that before you sauntered in two hours late.”

“It’s not my fault.”

“Nothing is ever your fault.”

“The train was late.”

“Should’ve taken an earlier train.”

“Salvo, basta.”

There was no more talking after that. He left, after kissing Mary’s feet.

“Let’s re-dress you, angel, shall we? What was your daddy thinking?” Gina dressed the girl warmly and wrapped her snug, then took her out in the carriage so they wouldn’t be cooped up all afternoon playing patty-cake and staring out onto Copp’s Old Burying Ground. “At least in the graveyard there are trees she can look at,” Salvo would say. “Anywhere else, poor thing would just be looking at a tenement.”

Trees and graves.

They walked slowly to Prince Park, with Mary suddenly deciding she wanted to push her own carriage, which added nine to thirteen years to their already lengthy excursion. They got a sandwich they split in half, caught the end of a late afternoon Mass at St. Leonard’s and then bought a few gifts for Christmas. Money was tighter than ever. Gina didn’t know how they would manage. Even the holiday ham was too much. She bought new knitting needles for her mother and a scarf for her cousin Angela, a beautiful red silk she spied in a tailor’s window. It was damaged on one side and imperfectly loomed, but the craftsmanship on the rest of it was superb. It was a real find.

She returned with Mary after six, fed her some cheese on a piece of bread, stacked blocks on the floor, waited. Salvo wasn’t back. Was this revenge for her own inadvertent lateness? He often did this. Stayed out knowing she absolutely had to catch the train home. She would be late returning to Lawrence, and then Harry would be upset with her.

Did her brother do this so her husband would be upset with her?

Mary’s mother finally strolled in around seven. She was a piece of work, that one. God knows what she got up to, out all hours day and night.

“What, he’s not back yet? Typical.” Phyllis yanked Mary out of Gina’s arms.

“He’s working.”

“Sure he is.”

“Mama, we got you Christmas things!” the little girl said, clutching her mother’s leg.

“You shouldn’t have bothered,” the blowsy, bedraggled young woman said rudely to Gina. “It’s tough this year. Where’s her coat? I have to go.”

“Maybe you can speak to Salvo when he comes back . . .” Gina said.

“I’m not waiting. You can wait until a cold day in hell for him to grace this apartment. No, we’re leaving. Come on, Marybeth, where’s your coat?”

“Goodbye, Aunt Ginny,” Mary said, hugging Gina around the neck. “Come tomorrow?”

“Not tomorrow, baby. Wednesday.”

Phyllis pulled her daughter away from Gina and rushed out without a goodbye. Gina stared after mother and daughter with a sick longing. What must it be like to have the right to pull your own babies out of other people’s arms. She stuck around for a few more minutes, hoping Salvo would return, and when he didn’t, she put on her coat and went out to look for him.

She hated walking past the brick wall separating the burying grounds from the street. It made her heart cold knowing that though she couldn’t see the gravestones, they were lurking there, behind a deliberately erected wall, as if they were so terrible that she shouldn’t lay eyes on them.

She found her brother in a tavern down Hanover, shivering in a huddle with drunk men spilling their brew onto the sidewalk and blowing into their hands to keep warm.

“Salvo,” she said, coming up behind him, prodding him with her hand. She pulled him away from the others, but saw he was in no condition to talk, or even listen. Gina didn’t have the answer to the eternal question: Did he drink so he could become unhappy? Or was he just an unhappy drunk?

Gina didn’t have answers to many eternal questions.

“Where’s the baby?”

That she knew. “With her mother.”

Salvo spat.

“You were supposed to come back by five so we could talk.”

“I got busy.”

She saw that. She was cold.

“I have to run now. I’ll miss my train. I’ll come back Wednesday.”

“Come earlier. Please. I’ll lose my job if I can’t work lunch. How is Mimoo?”

Gina shrugged. “She lost another domestic job. She keeps dropping things. But Salvo . . .” She struggled with herself. This wasn’t the time. But it was Christmas soon. “Will you come with Mary, spend Christmas with us? Please?”

Salvo shook his head. “You know I can’t. Also her damn mother takes her.”

“Don’t talk like that about the mother of your baby.”

“Have you met the beastly creature?”

“All the same. Just . . . swallow your pride, Salvo. For our mother. Bring Mary. Bring Phyllis too. One day a year, on Christmas, let’s bury the hatchet.”

“You know where I’d like to bury the hatchet,” her brother said, lucid enough.

“Oh, Salvo . . . what are you going to do, be angry forever?”

“Per sempre.”

“Please. Mimoo cries every night. She wants to see her grandchild for Christmas.”

“Her mother has her, I told you. Her mother, who, by the way, has found herself another fool to pay her rent.” Salvo swore. “Instead of talking to me, why don’t you tell that common-law husband of yours to go visit his family for Christmas? Tell him to go spend some time with them. Or tell him to go get a fucking job. Then I’ll come.”

“He is not my common-law husband.”

“Did you get married in a church?”

“Salvo.”

“Exactly.”

“You know he can’t,” she finally said.

“Can’t get a job? What a great country this is.” Salvo laughed. “Where one can live without doing any fucking work whatsoever. Can the immigrants do this? How many generations must we toil before we’re able to do nothing but sit around the table and pretend we’re smart?”

“Stop it, Salvo, you know he’s been working. He’s trying hard. It’s not easy for him. I mean, he can’t visit his family.”

“Oh, he can’t, can he? Well, I can’t either.”

“He can’t visit them because they don’t want him. That’s the difference. They want nothing to do with him. His father made that very clear. You know that.”

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

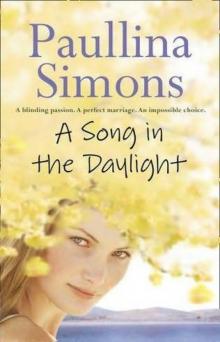

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)