- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 17

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 17

“What’s that yer wearing?” Monk pulls the stretchy Thermoprene of the wetsuit.

It’s not quite the nubile beauty queens pawing at his suit at the Silver Cross. Already what a disappointment this new world is. “I told you, it’s a time-travel suit,” Julian replies, pulling away. “Don’t rip it. Or I won’t be able to go back.”

“He’s right, Monk, best not touch him,” Miryam says, gesturing to Monk to step away.

Instantly obeying her, Mortimer, who wasn’t even near Julian, steps away, but Monk just laughs. “Jasper, get over here!” he shouts to a bull-necked, curly-haired teenager peddling some home brew from a large glass bottle. “Did you hear? Jack here’s wearing a traveling suit!”

“Oh!” Jasper says, affably rushing toward them. “Traveling suit from where?”

“He says from the future.”

“Brilliant!” Jasper is remarkably sanguine about time travel. “Let’s introduce him to my Flora, Monk. Flora is a fortune-teller most accomplished. You got any money, Jack, for a quick fortune? Flora will lap you up like milk, won’t she, Miri?”

“Don’t know, don’t care.” Miri lowers the dress hem that rode up above her mother’s scabbed knees. Agatha’s meaty legs are covered with unhealed sores. It could be syphilis. It could be impetigo. It could be anything.

Jasper and Mortimer are brothers. “Mort, smile,” Jasper says. “I made three farthings selling brew this morning.”

“Why should I smile because you made three farthings?” says Mortimer. “I’ll smile when they’re still in yer pocket come sundown.”

Jasper ignores his brother. “Jack, have you met Monk the dwarf?”

“I’m not a friggin’ dwarf!” Monk yells. Jasper and Monk tussle; Julian can’t tell if it’s play.

He pulls his hands behind his back. Julian is a boxer, and his hands are weapons. He’s a fighter who keeps his guns hidden and his fists unclenched. He hides his menace with fake solemnity. But he won’t shake their hands. He’s afraid they’ll know who he is by the strength of his grip.

While the hullaballoo continues, Julian reaches for Miri’s hand. He doesn’t mind that she should know who he is. Gasping in surprise at being touched, she tries to yank her arm away. “Miri,” he whispers. “It’s me.” He peers into her face.

She’s baffled. In this version of herself she barely comes up to his clavicles. Mallory’s mother in Clerkenwell’s brothels had obviously fed her baby better than Agatha has fed Miri, who looks permanently hungry, her face angular, the cheekbones gaunt, the jaw set sharply against her paper-thin skin.

He holds on to her another moment.

“You got the wrong girl, mister, I promise,” she mutters in confusion and turns to her complaining mother.

“I’m hot,” Agatha says. “I’m sweating. My legs itch like demons. And I’m hungry. Did you bring me something to eat, child?”

“Don’t scratch, Mum, you’ll open yer sores again,” the girl says, unbuttoning her mother’s cardigan. “I got to get the papers out. When I’m done and paid, I’ll bring you something. And I fed you this morning.”

“That was hours ago, luv. All you give me was bacon rashers.”

“And bread, Mum. And jam. And a tomato.”

“Hungry I am, is all,” Agatha says, patting Miri’s small hip. Julian watches the mother touch the daughter, noting Agatha’s scabrous arm.

“Miri, be a dear and brush me hair,” Agatha says, winking at Julian in response to his stare. “I want to look me best for our newcomer.”

Dear God. Julian backs away. He’s got to go. He needs to see if his money is still in the wall. Will he find it in 1775? Here’s his problem: to try, he needs masonry supplies. And to get masonry supplies, he needs money. Yet no one is offering him a job in St. Giles, probably because there are no jobs to be had.

And even if he does get the sovereigns out of the wall, he can’t step inside Goldsmiths on Cheapside to meet a coin trader in a body-hugging, nothing left to the imagination wetsuit. Eyeing Miri’s chums, Julian sees other complications ahead, large and small, dwarfish and tall, but right now he’s got to borrow some clothes from them. You must be dressed the part, or no one will buy what you’re selling.

Julian addresses the tall man. “Mortimer, I have a proposition for you. Do you have a suit, hat, and shoes I can borrow? Maybe a cloak, too?”

“I don’t hear proposition,” Mortimer says. “I hear begging.”

“I’ll return them tonight.”

“And I have a bridge I can sell yer. No.”

“Your clothes and two shillings.”

Mortimer shakes his head.

“Two shillings?” Monk squeals. “Take it, Mort, take it!” Mortimer and Monk turn to Miri for her approval.

“Forget Mortimer,” she says gruffly to Julian. “For two shillings, I’ll get you something. But no boots.”

“I need something for my feet.”

“Let’s take him to Cleon, Miri,” Monk says. “He’ll have boots.”

“Maybe Cleon has work for him, too,” Mortimer says with a sly gleam.

“Stop it, Mort,” Miri says. “He can’t work with Cleon, you can see he’s not a tosher. You’ll kill him, and I’ll never get my promised shillings. No.”

“What’s a tosher?” Julian whispers to Monk, but before he can answer, Miri shouts, perhaps even at Julian.

“What are you standing around for? Step on it! I don’t got all day. Some of us have work to do.”

The men spring to attention and follow her slavishly across the square to Lyon Street. Julian catches up with her. She’s out front like a sergeant. “Your mother needs medicine for her legs,” Julian says. His Thermoprene boots are torn and his bare feet touch the stones. His bare feet are touching these cobblestones. He won’t think about it.

“Oh, you’re a doctor, too, are you?” Miri snaps.

“A doctor?” Jasper perks up. Though Julian denies his medical pedigree, no one listens. “Mort, did you hear? Jack’s a doctor. Let’s take him to Aunt Hazel’s.”

“He said he’s not a doctor,” Miri says. So she is listening.

“It’s our aunt,” Jasper explains. “She can’t get out of bed.”

“If I had me a bed to sleep in,” Miri says, “I wouldn’t get out of no bed neither.”

Astrologers and alchemists abound as Julian and his new companions turn the corner on Monmouth Street, which centuries later will become Shaftesbury Avenue. Also everywhere: pickpockets, prostitutes, street sweepers, and street sellers. The children, like Julian, are barefoot. The women wear rags, and the fronts of many of their dresses are open, exposing their hanging breasts. Their faces are covered with sores. Empty bottles of gin lie on the street. Up above, Julian spots a man hanging by a rope on one of the balconies. “That’s Owen the Barber,” Monk says.

“That was Owen the Barber,” Miri corrects. “No one wants a cut or a shave, how’s he to make money, he’s in the wrong trade.” Below swinging Owen, two men and a child are stuffing a half-naked woman into a coffin. Julian assumes she is dead, though nothing is a given. “That’s old June,” Miri says unsentimentally. “She’s finally had enuf.”

June doesn’t look old to Julian. She looks thirty.

A man chases a young boy with a mallet. Apparently the boy stole his bottle of gin.

“Kilman Distillery is on the next street over,” Monk explains to Julian, without any ironic emphasis on the word Kilman. “In the afternoons everybody goes a little crazy on Gin Lane.”

“Could it be because the gin’s mixed with turpentine?” Mortimer says with distaste.

Miri marches ahead, skipping over a dog and his owner, who are lying on the ground, faces to the stones, gnawing on the same denuded meat bone. She weaves past carts of rotting apples and buckets of slop, past men wolf-calling in her direction.

Between King Street and Drury Lane, they duck into an unnamed alley and Julian follows through a passage so tight he must walk it sideways. These inner

tenements are hidden from the street. A sign with an arrow pointing down into the decrepit darkness reads: DRUNK FOR A PENNY. DEAD DRUNK FOR TWO. CLEAN STRAW FOR NOTHING.

They cross an interior square called Neal’s Yard and approach a canal that smells worse than anything Julian has ever smelled. A rope bridge hangs over it, and one at a time, they walk across. Julian is the only one who holds on to the ropes for fear of losing his balance and falling in. Miri and the three men sprint down the swaying bridge like cats. In the next tenement they descend a long flight of stairs into the gin cellar.

There is an open sewer in the middle of a large windowless room, maybe twenty feet wide. People sit around the pit on benches and on the ground, chatting and drinking. Their clothes hang drying on lines. Julian wishes he could hold on to something.

“I can see by his deathly pallor our traveler has never been to the cellars of St. Giles,” Monk says, with great amusement. “But clearly you’ve heard of them, Jack.”

“Oh, yes,” says Julian.

“The pit’s here on purpose. It’s not ’cause we dirty. It’s to keep the barnyard constables away from our treasures. It’s like a castle moat.” Monk laughs and jumps over the pit. Miri, Mortimer, and Jasper are already on the other side. Only Julian is left. Julian—who flew over a black chasm in a sightless cave, much wider than this puddle of raw sewage—can’t get his legs to obey him. If he falls into the pit, he’s dead. He won’t recover.

Somehow he leaps across. They laugh at him, even Miri.

Especially Miri.

I just leaped over a cesspool for you, Josephine, Julian thinks. Impressed yet?

In one of the open rooms a level below the drains, a woman lies moaning on a fleabag mattress on the floor. It’s Aunt Hazel. The woman seems fine, if a little frail, and if you discount the part where she lives below a sewer in a room with no windows. Jasper hitches up his aunt’s skirt to expose her blue veiny calves. “Can you help her, Jack? She’s our only living relative.”

The woman speaks. “Well, no, Jasper. There’s also yer no-good uncle on Jacob’s Island. He’s got all yer new cousins by them scags he fiddles.” She looks up at Julian expectantly. “What’s wrong with me legs?”

Julian knows that claiming ignorance is not an option. Miri is watching. He must fake wisdom. He needs Miri to trust him enough to help her mother. He strokes his chin, eyeing the bulging veins. “Madam, you have a leg swelling, but tell me, has it been accompanied by a ringing in your ears?”

“Oh yes!”

“Any unusual thirst?”

“Very much so. Have you got some gin to quench it?”

“All in good time. Joint pain?”

“Every minute! Only gin will cure it.”

“What about occasional mania? Bursts of activity followed by energy depletion?”

“Not recently, but otherwise yes, me whole life.”

Julian continues to stroke his chin and finally makes his prognosis. “You, madam, have a wraith deficiency!”

Mortimer, Jasper, and the aunt nod vigorously. Miri eyes him with half-amusement, half-skepticism. “Yes,” the woman cries, “that’s what it must be! What’s the cure? Gin?”

“Chickweed,” Julian replies. “And sunlight. Thirty minutes a day.”

“Sunlight? No, thank you. And I ain’t got no chickweed.”

“You’ll need to get some. Apply the chickweed directly to your legs. If you can heat up the plant, even better. You can get it at any apothecary. I can pick some up for you, if you like.” Julian fakes a stern voice. “But I can’t pick up sunlight for you, madam. That you must get for yourself. Agreed?”

Aunt Hazel nods gratefully.

“Don’t thank me yet,” Julian says to the two softened brothers. “Let’s see if your aunt gets better.” He glances at Miri, hoping she’s impressed.

Turns out not only is she not impressed, but she’s vanished.

∞

Two corridors, four rooms and another cesspit later, Julian is lost, but the boys have finally arrived at Cleon’s door. If the men decide to turn on him, Julian’s a goner. If they thought there was anything on him to rob, they could kill him and dump him into the black hole of sewage, and no one would be any the wiser.

While Mortimer steps inside the room to wake up Cleon, Monk, and Jasper advance on Julian in the hall to interrogate him some more. Julian forces his hands to stay behind his back.

“So who is you, really?”

“Where’s you really from?”

“I told you, gentlemen.”

“They ain’t got normal clothes in the future?”

“They do. The suit is for swimming.”

“Where could you possibly be swimming—the Thames?”

“Maybe that’s where Fulko should go to hide, Monk,” Jasper says. “The future.”

Julian is about to ask who Fulko is, but Miri returns with a fine dark suit for him, a billycock hat, and a long black silk cloak. Where would she get attire as high-quality as this? “Two shillings, you promised,” Miri says. She has changed her clothes. She’s put on a long gray skirt with no petticoat and an embroidered, patched-up, cropped blue jacket. It could be the nicest thing she owns. Her man’s cap has been replaced by a white bonnet. She has brushed her short straight hair, she has washed her face. Julian can’t tell which is the disguise: the cleaned-up young woman in front of him or the one before, in rags.

“What d’you think of me fine idea, Miri?” Jasper asks. “After we spring Fulko from Newgate, your husband-to-be should go and hide in the future with Jack.”

“Only if I get to go with him,” Miri casually replies. She’s hard to excite with all this talk of a future she hasn’t seen and doesn’t believe in.

“Who’s him in that sentence?” Julian says. “Me? Or your husband-to-be?” He grimaces at his own words and leans against the wall for support. She has a fiancé? Not again. Can’t she ever, just once, come to him not in a brothel or encumbered by Lord Falks and Fario Rimas? One single time. “What’s he in for?”

Monk gets vague, refuses to answer. “Robbin’, mostly.”

“Lift that, draw that,” Jasper concurs. “But now he’s facing the chats.” Chats are gallows.

“Could he be facing the chats, Jasper,” Miri says, “because a man died while Fulko was fleecing him?”

“The mark had a bad heart,” Monk cries. “That’s not Fulko’s fault!”

“Tell that to the judge, Monk,” Jasper says. “Unless you and Miri do something, your brother is gon be hanged at Tyburn a fortnight past the summer solstice.”

The Fulko character is Monk’s brother? Oh, the tangle of these men and the girl.

“He won’t hang,” Monk says fiercely. “By all the stars in the heavens, he won’t hang.”

“There’s a bloody code in the Old Bailey.” Miri stares into her shoes. “You know that, Monk. A hanging for a death.”

Better than before, Julian thinks, when it was being boiled in oil for a death.

“He did it for you, Miri!” an aggrieved Monk cries. The mood in the corridor shifts. A minute ago they were joking. Now it’s a good thing no one’s carrying knives. Julian drops the clothes she has given him on the ground to free his hands. He can’t tell where this is going.

“I didn’t tell him to kill no man,” Miri says. “Robbin’ is one thing. But killing is wrong.”

So in this incarnation, she is against wanton murder. Good to know.

“You told him you wanted to get hitched. He was saving for your nuptials!”

“By saving you mean robbin’?”

“You said you was gonner get him out, Miri,” Monk says in a threatening voice. “You said.”

“Okay, Monk.” That’s Julian. “Why don’t we calm down.” One more exchange like the last one, and Julian is going to have to come between Monk and Miri. Nice way to make new friends.

“You know what Pastor Wyatt told us to do,” Miri says. She is not intimidated by this Monk fellow. She doesn’t s

eem to be intimidated by much. “We need to cobble together four pound to pay off the magistrate. We both have to do it, not just me. You two pound, me two pound.”

“I know that’s what he said, I ain’t stupid,” says Monk.

“How close are you to your two pound?”

“Within a couple of farthings,” Monk says. Four farthings make a penny. “You?”

Miri shakes her head. “Real money, Monk, not your counterfeit bullshit.”

“That’s right, real money, Miri. You?”

“Yeah.” The girl doesn’t look at him. “Me too, Monk. Within a couple of farthings.”

False coining is a betrayal of the realm. In 1666, Constable Parker had five people hanged in Westminster for counterfeiting. Julian wonders what the punishment is these days.

“Miri works as a pure finder, Jack,” Monk suddenly says, with a cruel gleam.

“Monk!” She shakes her head.

“What? I’m just telling Jack how you make your money to get your fiancé out. Miri picks up dog mess off the streets and sells it to tanners who use it to cure leather. Don’t pay very much, does it, Miri?”

Julian’s mouth twists with pity. He can’t look at her.

“Cleon!” Miri yells, banging at the closed door. “Let’s go! I can’t wait all day.”

“Jack, you need money?” Monk asks. “Go work for Cleon. He’s been looking for a new helper since Basil died in a sluice.” The suddenly pious urchins cross themselves.

“Sluice?”

“Yeah, poor fucker got caught in a sewer sluice when the water level rose too fast. The tidal wave of sludge shattered him to smithereens. We couldn’t find most of him.”

“We looked,” Jasper says.

“Oh, we looked so thorough. We found a foot.”

“And a hand. Don’t forget the hand.”

“Not a whole hand,” Monk says.

“Almost. It was only missing those two small fingers.”

When Julian refrains from the reaction that Monk was clearly looking for, Monk elaborates. “Cleon is a sewer hunter, a scavenger. Been down there seventy years, looking for this or that. What do you say, you wanna go work for him?”

Julian says nothing. What an actor he is! Josephine’s got nothing on him. He waters the shantytown version of Josephine with his fertile gaze. The flower reacts poorly. She shrivels.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

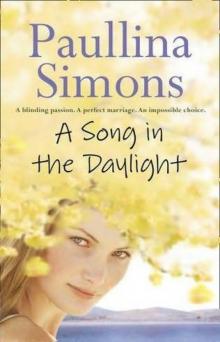

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)