- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 16

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 16

He was doing it for her.

Julian, go and come back for me.

12:00.

Part Two

In the Fields of St. Giles

“O, you shall be exposed, my lord, to dangers, As infinite as imminent! But I’ll be true…Will you be true?”

Cressida to Troilus, William Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida Act IV, Scene 4

13

Rappel

FIRST WAS THE LABYRINTH, A NARROW MAZE OF FISSURES and dead ends, nowhere, nowhere, nowhere, walking and aching for miles in his dive boots on the uneven cave floor. The boots ripped. Thermoprene wasn’t meant for serrated-edge ground.

Julian moved through crevices—treacherous, utterly infuriating. The height of the walls was ten feet, but the width was between three feet and eighteen inches! It was so narrow in places that Julian had to creep sideways as if on a window ledge, his back against the wall. The hard-shell pack on his chest made him too bulky. He had to take it off and carry it in his hands. Often these crevices ended abruptly in a hill of stones, and he had to double back and head into a different fissure, climbing over boulders, searching for a one-man slot that might lead the way out. The claustrophobia of the maze was matched by his stifling frustration.

And because nothing is so bad that it can’t be made worse, he tripped over his shredded boots and dropped the backpack. Julian tried desperately to catch it. It careened off a stone, teetered for a moment on a ledge, and then slipped through a crevice and disappeared before Julian could grab the strap. He cursed wildly for five minutes before he resigned himself to the backpack’s loss and resumed his trek. Like he always said, you can’t overprepare, and in the end, it won’t matter. Why was it still so hard to accept how many things were out of his control.

When he finally climbed over a rocky protrusion and walked out onto a mesa above a cave chamber, he wished he were back in the suffocating web of stone. The high plateau where he stood over a canyon was covered with cones, limestone deposits, rocks and cave matter. These prevented him from walking, much less running and leaping. The growths were three-dimensional etchings rising from the ground, appearing to him as writhing monsters, as grisly beasts. In the beam of his headlamp, their shadows, tall and self-important, reflected off the cave walls.

He stood at the rim of a miniature Grand Canyon, if the Grand Canyon were contained in a closed space the size of two airplane hangars, one on top of another, and instead of the sun and birds and evergreens and the sky, there was nothing but rutted darkness. The things that looked like birds and trees were stone. It was the Grand Canyon without any of the grandeur and with all the peril.

A thousand feet below him, the river he needed to get to carved through the canyon floor, emerging from one end of the cave and meandering into the other. The perfectly round moongate rose over the river’s right exit. The waters flowed through the moongate. There was no jumping over this chasm. To get to the bottom, Julian had to rappel the steep canyon wall with a useless harness and without rope or an anchor because all the rope and anchors were inside his lost backpack.

Watch out for falling mountains, like in Topanga, Ashton told Julian. No danger of that here. The only thing that would be tumbling off these cliffs was his sorry ass.

Julian had no choice. He scaled down a thousand feet, hugging the canyon wall.

Dripping water had hollowed out holes in the vertical rock, like jug handles. The surface was jagged, uneven. It took him infinite time, using the rule of three. Three limbs always attached to the wall—two legs, one arm, two arms, one leg—finding a step or a ridge to hold on to. His headlamp illuminated the rock four inches from his face, and nothing else.

Why couldn’t Julian have crampons to help with his descent today, when he could most use them? Instead of cleats, he had torn slippery Thermoprene on his feet.

One misstep, one mishandling, one ridge not wide enough for his gloved hand, one stony lump not large enough for his barely clad foot and down he’d go, careening against the stone with her crystal and beret.

To navigate down the canyon wall, he needed a cord and spikes, he needed an anchor, a hook, belays, carabiners.

But Julian didn’t have those things. He had nothing.

He crept down the ravine harnessed to nothing but his red faith.

∞

He reached the bottom by falling the last ten feet. He landed roughly and lay on his back on the pebbly shore, gathering himself. His headlamp was dimming. No wonder. He must have been glued to the wall like a salamander for a hundred thousand hours. It was a good thing he’d brought another headlamp and stuffed it inside his wetsuit.

The enormous canyon above him was a live ominous presence he couldn’t see but strongly felt. It pressed down on his chest. He rested for barely a few breaths. He had to hurry. She was waiting.

Wading into the river waist-deep, Julian chugged down handfuls of cold cave water, hoping it wasn’t the water of forgetfulness, and swam through the moongate, looking for something to grab onto and float. He felt better in the water, invigorated even, after the physical and mental stress of his interminable free-climb descent. He had made it over the bright black chasm. Now the river would take him to her. Very soon he would see her face. If only he could tell her from the start how much he had missed her, having lived a lonely year without her. And though Julian was relieved he had made it, he was frightened of what lay ahead. It had been such a worrying supernatural effort to get to the river. Almost as if he was being kept from her.

He had no trouble finding something to drift on. The river was filled with crap. Julian had his pick of garbage. He grabbed onto a small door and found a narrow board to use for an oar. Balancing in the middle of the panel, he sat cross-legged and paddled through the rubble.

What was going on with this river? Like a tsunami had swept through and washed a demolished city into the water. Was he hallucinating? In the beam of his waning headlamp, the river looked filled with human things. Fragments of chairs, segments of walls, washboards, empty buckets. The flowing debris got trapped in the bends as if under the starlings of London Bridge, piling up higher and higher, narrowing the river and increasing the pressure of its current. Paddling became impossible. Julian threw away the oar but didn’t lie down. The flow was too strong. He’d get thrown off if he relaxed his body.

Were there other humans on it? He called out. Only his voice echoed back. Were the humans dead, except for him? Did they run to the river and die, leaving their things and bodies behind? Or was the river where they lived, amid the junk, wet with life?

And what was more frightening?

The descent down the cliffs took a lot out of Julian. He didn’t have a moment to recover before being hurled into the junkyard flood. He had to be at full attention. There was no floating, no drifting, no sleeping. He turned off his light to conserve it, saved the other one for the just in case, and swirled in the darkness. He kept getting knocked into impassable hard things and navigating out of piers built up from refuse.

Where was he headed that this was what he had to overcome to get there?

Josephine, I will follow you to the end of forever. Julian tried to close his eyes for a moment. But where are you taking me?

After what felt like years, he was tossed from his useless carriage into shallow water.

14

Gin Lane

JULIAN REALIZES HE CAN SEE THE CONTOURS OF THE CAVE, even without the headlamp. Light is coming from elsewhere. Thank God, because he couldn’t have taken much more. Before he starts forward, he unbuckles and throws off the harness. That Ashton and his adorable desire to control what couldn’t be controlled.

To climb out, Julian moves boulders and trellises out of his way. There’s a musty unpleasant smell around him, and mud underneath his feet. At least he hopes it’s mud. The light filters in through a small break in an exterior wall, a hole mostly plugged up by a giant object blocking Julian’s way out. He pushes at the object with his gloved hand. It’s

mushy, it gives way, yet doesn’t give way. He takes off his glove and tries again. It’s pliant but won’t budge. He pushes on it with one hand, then two. If he didn’t know better, he’d say it feels like a woman’s generous rear end, but that’s silly. He’s not crawling back in time past a woman’s ass.

He taps on the squishy bottom. He knocks on it as if it’s a door, waiting to be opened. He slaps it. As a last resort, he pinches the thick skin under the loose fabric. There’s a yelp, a curse, motion and commotion.

Now we’re getting somewhere.

“Yowse!” a female voice shrieks. “A rat just bit me arse!” The enormous shape shifts barely an inch. Julian pinches the flesh once more, but harder. Finally, there’s significant movement. He shoves away the stool and squeezes past.

A large woman with a bloated face stands staring at him in wobbly confusion, her dim eyes widening. “Why are you pinching me arse, scoundrel?” she says in a thick common tongue.

England again. Is he never leaving England?

Rather, is Josephine never leaving England?

“Why are you touching me delicate parts? I’ll have you arrested for lewd acts of wanton disregard for me human flesh! Constable!”

No constable comes.

Julian, still on his knees, looks around. The woman isn’t the only squalid thing here. Able-bodied men and boys in shabby frock coats loiter on the cobblestones. A few women in stiff excessive crinolines lean against the buildings.

It’s fetid and damp. He sees seven streets like spokes, criss-crossing the square. Julian stops paying attention to the chirping woman.

Fuck.

He realizes where he is. Not only is Josephine never leaving England, she seems to be never leaving London. And what a London this is. He has followed her into Seven Dials, the maze of streets between Covent Garden and Soho, followed her into the Seven Dials not of today but of yesterday.

O London! Why, you magnificent city, why? All your marble palaces and gilded gardens, your broom-swept streets and river embankments, you could’ve spit her out anywhere. Why, of all places, here?

Seven Dials is the heart of the rookery of St. Giles in the Fields, one of the worst slums in London. Julian doesn’t need to learn the year. He knows. It’s sometime after the Great Fire and before 1845 when the city tore down half the rookery to transect it with Oxford Street, hoping that the new shopping boulevard might reduce the numbers of shiftless vagrants. The ooze of primordial morass seeps over the cobblestones, the foul fumes rise in the air. From every graveyard lane to every decrepit dwelling, it’s clear to Julian that 1845 is still the far-away future.

Rookery: a collective noun for a breeding ground for animals.

Rookery: a place where birds are confined, noisy birds like ravens.

Rookery: a colony of penguins.

Rookery: St. Giles in the Fields.

Kneeling at Seven Dials, Julian prays to St. Giles, the patron saint of cripples and lepers. He can see the church’s pale white spire needled above its parish. In 1603 he took Mary past that church rising over Drury Lane. They rode their wagon through fields of flowers, reciting Shakespeare. Fields of asphodel surrounded the church then. Marshland and open ditches surround the parish now. And within: hovels and gin shops. Not even brothels, that’s too precious and quaint. Sex for sale straight up on the undrained streets.

Seven Dials. Again the number seven, a number that has subsumed him.

Seven times for her soul.

Seven sins, seven ages of Josephine.

Seven weeks for him to save her.

And how can he save her here? She might not have seven days to live here.

Seven is nothing but a foul metaphor for his existence. And hers. Because a 7 looks like the gallows.

The square is dissected by three streets plus one for bad luck. The roads that divide Seven Dials are impossibly narrow, in all epochs, past and present. One small car can barely fit between the sidewalks. There are no cars or sidewalks in the slum today. The cobblestones are glued together with the mortar of muck. The plaques on the corners read Great Earl, Little Earl, Great Lion, Little Lion, Great St. Andrew, Little St. Andrew—and Queen Street. The famous Doric pillar that stands in the middle of the square and acts as a sundial is missing.

Is this going to be Julian’s fate? A circus with seven gates, seven spokes, seven streets, seven threads, all leading to the same dead end?

It is so ordinary that he should be on his knees in a crowded public place that no one even notices him except the heavy woman on the low stool. The mangy court is mobbed, yet no one’s moving. The crowd is drinking, squabbling, singing—and it’s not even night. From the patch of sky, Julian guesses it’s early afternoon.

After a heavy sigh, he rises to his feet. He feels unhinged—as if anyone could tell. He decides to spout some nonsense himself. “Ladies! Gentlemen!” Julian calls out. “What year is it, I beg of you!”

The heavy woman barks, “Are you dull in the head, boy? It’s 1775.”

“Oh, 1775!” Julian exclaims. “Splendid! Then my time machine worked!”

“Good on yer, mate!” a wily young man rejoins, traipsing by with a basket full of plums. “What’s a time machine? Keep up the good work. In that spiffing suit, you can go anywhere.”

“Don’t you worry, ladies and gentlemen!” Julian shouts, enunciating every word like a carnival barker. “It’s hard to believe, but I promise you, your Seven Dials will soon be a unique retail and leisure destination!”

People respond by laughing. They don’t stop drinking. Loosely they collect around him to listen. They were bored in the middle of their day, and suddenly a sideshow. “Seven Dials will be home to over 120 quality shops! Home to five West End theatres! Home to two luxury hotels!”

They guffaw. The undersized plum seller, a slim costermonger in a shabby frock, offers him a sip of brew to keep him going. Julian is thirsty; he gulps it down. It’s strong, not like that weak tea of an ale that Krea used to make. “Hotel Covent Garden will be just a few steps away on Monmouth Street!” he yells, wiping his mouth. “You’ll be able to get a two-bedroom suite with a terrace overlooking this beautiful city for a special bargain price of only 867 pound sterling!”

When Julian spews to the vagabonds that a hotel a few steps down from where they spend their aimless days will cost nearly 900 pounds, which is a sum they’ve never heard of, much less made as a total sum of all sporadic labor in their lifetimes, they still howl—but less cheerfully. They suspect he’s mocking them.

“I’m not mocking you, good people, not at all. I’m telling you this to raise your spirits,” Julian continues, undaunted by their hostility. “Fret not!”

“All right, mate, pipe down,” the diminutive costermonger says. “How about you gimme a farthing for the liquor you took from me.”

“Shut yer pie hole, Monk!” the heavy woman on the stool screeches. “He’s a nice boy! He touched me parts like I was a lady!” Toothlessly she grins at Julian. “I’m Agatha, pleased to meet ya.”

“Pleased to meet you, too, my dear Agatha,” Julian shouts. “Where’s your sundial pillar? The most famous Doric pillar in the middle of your resplendent square, what’s happened to it?”

“Demolished two years ago,” a breathy voice replies by Julian’s arm, and before he turns his head, he knows it’s her. His rantings have brought her to him. Well done, Julian Cruz. Now you can stop. Underneath the devil-may-care vaudeville, he is despondent. Look where she has led him.

He lowers his gaze on a petite creature in sexless rags, militant of face, short of hair, unsmiling, and soft as a pair of bolt cutters. Her pale, open, wide-boned features, her large mistrusting eyes, her pursed lips are smudged with the slum. His eyes watering, Julian stares deeply into her face. His happiness and misery must be on full display and must be incongruous, because the girl, a dirty thin scavenger, glares back at him, perplexed and defiant.

“Why did they demolish it?” he asks her quietly. The fight has gone out

of him. He wants to press her to his chest.

“The city wanted to stop cracks and crooks like you from staging it as their meeting place,” she replies, leaving his side and walking over to Agatha. “Has he been bothering you, Mum? Wanna get up, stretch yer legs?”

Agatha is her mother!

He should’ve known. All the mothers’ names begin with A. Ava. Aurora. Anna. Now Agatha.

“Bothering me? No. He pawed me with his male hands!” Agatha says. “Last time I was manhandled like that was when your dear papa and me fadoodled, may he rest in peace, the cheating no-good drunken dead bastard.”

Someone grabs Julian’s sleeve. It’s grubby Monk, with black teeth and in black rags, solicitously offering Julian more brew. Another man steps forward, this one over six feet tall. He’s wearing a suit but his hair is unwashed and uncombed. “Why were you staring at our Miri over there?” the giant demands like the Grand Inquisitor except more dour. “Do you know her?”

Our Miri?

“Calm yourself, Mortimer,” Miri returns. “He don’t know me.”

“Are you sure about that?” Julian mines her face for a blink of recognition. He doesn’t need much, just a trace.

She blinks all right—with insurrection. She is uncommonly wary of him. “Did someone cloy your peck?” Ah. Now Julian understands. She thinks he suspects her of pickpocketing him. “Wasn’t me, mate, I promise you,” she says. “I don’t go near the likes of you. You got the wrong girl.”

Julian shakes his head, but before he can speak, Agatha shouts, “Miryam! Don’t be rude to our kind gentleman, or he’ll clump yer. Where are yer manners?”

Miryam, sea of bitterness, sea of sorrow. That’s what her name means. Julian lowers his head to look for his bearings on the cobblestones. The tall man and the small kid continue to flank him, curious but also guarded. They both smell awful. Mortimer is in his twenties, but Monk can’t be any older than twelve or thirteen.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

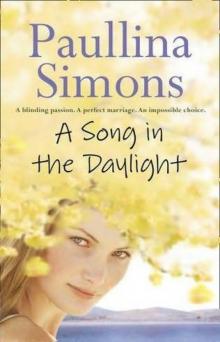

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)