- Home

- Paullina Simons

Six Days in Leningrad Page 7

Six Days in Leningrad Read online

Page 7

“I think so,” Viktor replied. “The tram runs through it, see?”

“Yes, yes.”

“Maybe there is a street sign?” I offered helpfully.

“No,” Papa barked. “There are no street signs.”

We drove around some more.

“Papa, have you been here before?”

“Of course I have, several times, but it all looks the same.”

“What number building is it?”

“Thirty-eight, but that won’t help. There are no numbers on the buildings.”

“Oh.”

“Look!” my father exclaimed. “I think that’s Ellie on the balcony, waiting for us.” We pulled up to a building, got out of the car, and my father waved. The woman on the balcony didn’t move. “No, it’s not her,” he said, shoulders slumping. “But I’m pretty certain this is the building. I’m almost positive.”

We thanked Viktor, asking him to come back for us a little later that evening, and then walked up to the front door. My father had his two heavy luggage bags. I carried one while he carried the other.

“Do you know what apartment number it is?” I asked.

“Yes,” he said. “Number nineteen.” He sounded unsure. The door had no handle, no lock, no hinges — just a vertical metal bar running down the length of it. It almost didn’t look like a door, but a metal wall, hermetically sealing the building from the outside.

There was no list of apartment numbers, no names, no doorbells, no intercom. Instead there was a contraption like a giant combination lock. To my surprise, my father seemed to know what to do. He turned three dials on the combination lock on the rebar — one to 0, one to 1, and one to 9 — and pressed a button.

In a few seconds, there was a buzz and the door popped open an inch. Papa grabbed the metal bar and pulled it open the rest of the way. We walked into a tiny, dark, low-ceilinged entrance hall that smelled of (very) old urine. Not that new urine would have been much better.

The elevator was at the top of a narrow stairway. Why did we have to walk up seven steps to get to the elevator? Haven’t the Russians heard of the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act? As we climbed the stairs, we had to hold the bags out in front of us: there was no room on the staircase for a person and a bag side by side.

As we waited in the gloomy hall for the elevator, I tried to make conversation. “So . . .” I asked, “Babushka’s and Dedushka’s building was really like this?” Not hiding my skepticism.

“Almost,” my father said. “Theirs didn’t have an elevator.”

The elevator door opened; my father hopped in, and the door promptly started to shut behind him. I shoved the bag into the doorway, but it kept closing, unmindful of me or the bag. For the next fifteen seconds the door and I engaged in a fierce battle of wills while my father stood and watched with the detached helplessness of a television viewer.

Finally, I won, but it had been by no means a certain victory.

Out of breath, I got into the elevator and asked my father what seemed to me a reasonable question to ask of a man in an elevator.

“What floor?”

At first I thought he hadn’t heard me. I was about to repeat myself when he said with a chuckle, “I really don’t know.”

“I thought you’ve been here before.”

“Many times. But I can’t remember the floor.”

The number of the apartment was 19. What floor would that be? Using logic and inferential deductive reasoning, what would we in America do?

“Is it on the first floor?”

“No, definitely not.”

“Is it on the nineteenth floor?”

“The building has only nine floors.”

“Maybe it’s the ninth floor?”

“No, they’re not on the top floor. I’m sure of that.”

The elevator door remained calmly open, as if, now that we were inside, it had no intention of ever closing again.

My father pressed a button.

“Maybe it’s eight,” he said. “Although I don’t think they’re up so high.”

The elevator creaked up to the eighth floor. The doors opened halfway, then began to close again. I squeezed myself into the gap, through the vise-like grip of the doors, and then pried them open so my dad and his bags could get out, too.

We stood on the small landing in front of three apartment doors, none of which was open.

“This is not the floor,” Papa said. Then he walked to the stairwell and yelled. “Ellie? Ellie!”

From below us, a woman’s voice yelled back, “Yura!”

“Ellie! Where are you?”

“I’m coming down!” Ellie yelled.

We heard footsteps somewhere beneath us, heading farther down the stairs.

“No, don’t come down. We’re up! Up on the eighth floor.”

The footsteps stopped. There was a pause.

“What are you doing up there?” she asked.

“I forgot what floor you’re on! What floor are you on?”

Ellie laughed. “We’re on fifth.”

“Fifth,” I said. “Of course.”

“Wait, we’re coming down,” yelled Papa.

On the fifth floor, Ellie was standing on the landing, waiting for us. I hadn’t seen her in twenty-five years, yet she looked just as I remembered her. She was blonde and little with the same sweet, small-nosed, freckled, smiling, clear-eyed pixie face. Her arms were open to embrace me.

She showed us into her apartment.

“Where is Anatoly?” my father asked.

“He is getting bread. He’ll be back soon.”

Ellie gave me a tour of the apartment. It was tiny, much smaller than my family’s first American apartment in Woodside, Queens. They’ve been working all their lives, I thought, and they still live here? But as she proudly showed me her pokey kitchen with its sunny view, I realized with shame that she thought she had done quite well to have such a nice home.

I made a note not to be such a judgmental idiot.

There was a short corridor with two narrow doors. “One is the toilet, the other is the bath,” Ellie said. “Do you need the toilet?”

“Not right now.”

“I’m going to put my things down and take a shower,” my father said. “Is that okay, Ellie? Before dinner?”

“Of course,” she said.

My father would be occupying the computer room for the next six days. There was also a living room, a small front bedroom, and a narrow concrete balcony that overlooked Ulitsa Dybenko. I guessed that it had indeed been Ellie who had stood on the balcony and watched us as we pulled up in Viktor’s car. She probably hadn’t been sure it was us.

When we got to the bedroom, Ellie said, smiling, “Plinka, why don’t you stay with us? As you see, we have plenty of room for you. We could give you our bed.”

“No, stop it,” I said. “Where would you sleep?”

“Oh, we’re living at our dacha now.” Many Russians live at their dacha — their summer house — during the warmer months.

“Where is that?”

“Lisiy Nos.”

I shook my head. “I don’t know where that is.”

“Across the gulf from your Babushka and Dedushka’s dacha in Shepelevo.”

“That’s where we’re going tomorrow, by the way,” my father pitched in from the other room.

“Oh, so you’re in Karelia?” I said excitedly to Ellie. I planned to set part of my book there. “Papa, how do you say in English? Is it peninsula?”

“No, not peninsula,” he called out. “Peninsula is surrounded by water on three sides, isthmus on two. It’s isthmus.”

“Oh.”

He stuck his head in. “So what two bodies of water surround the Karelian Isthmus? Do you know?”

“Ha! Of course I do,” I said, thinking furiously. “Gulf of Finland and Lake Ladoga?”

He laughed. “Why is there a question mark at the end? Are you asking me or telling me? Because I know.”

&nb

sp; I spotted an empty bottle of Lancôme’s Trésor perfume on the nightstand.

“Your mother gave me that perfume, when she was here last,” said Ellie. “It’s all gone, but I really liked it. The bottle still smells of it a little.”

The floor was warped hardwood. The cabinets, the tables, the red curtains, the bed, the bed stand — were all simple and old. Only the dark wallpaper looked new.

I wanted to say something, anything, so I nodded at the walls. “Nice wallpaper.”

“That?” Ellie said dismissively. “Nah. What about this?” She led me back into the living room. There, the wallpaper reminded me of the place I had lived in in England, a former council house. Paper that had once been yellow but was now a sooty gray with cigarette smoke. Paper my first husband and I had spent money we didn’t have to remove. Ellie smiled. “It’s from Europe.”

“Oh,” I said. “Europe. Very nice.”

My father reappeared, all fresh and washed.

“Did you have a nice shower?” Ellie asked. “Plinka, maybe you want to have a shower today? The water is nice and hot. Have one. Because tomorrow they’re turning it off.” She chuckled.

“Oh yeah?” I said, chuckling right back. I thought she was joking. “Don’t worry. I can have a shower at the hotel.” I paused. “When will they turn your water back on?”

“August fifth.”

I stared rather dumbly at her. “Three weeks from now? You mean you’ll have no hot water?”

“Yes.”

“In the whole building?”

“Right. So will you stay? You can sleep in our bed.”

Before I could answer, my father interrupted. “No hot water? That’s no good. Paullina, I’ll have to come and shower at your hotel.”

Before I could reply, Anatoly came home.

Anatoly and my father had known each other since 1952, when my father was sixteen. They had known each other ten years before my father even met my mother, eleven before I was born. If it weren’t for Anatoly, there would be no pictures of me as a baby. He was the only one in those days with a camera, and even a film camera. He was my official photographer. Every single photo of me as a child was taken by him. If not for Anatoly, there would be no home movies of three-year-old me being stung by a bee while eating watermelon in the Red Cave in the Caucasus Mountains by the Black Sea. If not for Anatoly, there would be no footage of my mother and father meeting and falling in love in a seaside resort town in 1962.

I was dismayed by how gaunt Anatoly was. He was only one year older than my father, but the ragged lines in his face made him look much older. I remembered Anatoly as such a happy, slender, funny man.

He was still funny — and slender. Withered, maybe.

A few minutes later, Anatoly’s brother Viktor and Viktor’s wife Luba arrived. Viktor and Anatoly were twins.

Viktor’s only son, Paul, had left Russia some years ago to study engineering in Princeton, New Jersey. I had met Paul when Kevin and I were living in New York; Paul had come to our house to celebrate New Year’s 1995. He was a polite young man of about twenty, very inquisitive. He walked around my entire house, looked at every book on my shelves, pressed every button on my VCR and laser-disc player and TV, crashed my computer, and got hold of my camera. When I developed the photos, I discovered that he had taken pictures not of my kids, or the Christmas tree, or the people at the party, but of an empty cake plate. A dirty fork. My cat sleeping under the table.

I shared this now with his parents, Viktor and Luba. They laughed joyously and said with adoration, “Yes, Pasha is like that. He does the same at our house when he comes to visit. He is always adjusting the color temperature on the TV.”

I asked what he was doing nowadays. They told me Pasha had recently married a Russian girl and taken her back to Princeton with him.

Finally Ellie and Anatoly’s daughter, Alla, arrived. She showed up with her husband — another Viktor — and their two children, Marina and Andrew.

My childhood friend Alla looked remarkably lovely and remarkably as I remembered her. Her hair was short now, but her freckles were the same, her upturned nose, her round eyes, and she was still taller than me. And still two years older. This pleased me: I wasn’t the oldest young person in the room. I liked the grown-up Alla immediately. I had liked the young Alla, too. She had taught me how to play cat’s cradle and eat watermelon. Every time our parents got together, we were together, which meant we were together a lot. She wasn’t a reader like me, but because of that, she was more social and had more friends. She was always the popular one.

Alla’s husband Viktor was good-looking in a generic European sort of way; he didn’t look particularly Russian. I thought he was our age; when I found out he was forty-four, I was shocked. There was no kidding yourself with forty-four: it seemed so old.

I realized shamefully that I was underdressed and had no hope of becoming overdressed on this trip unless I went shopping. Alla and her husband were wearing suits; the kids were in their Sunday best. Luba wore a dress with stockings and black high-heeled pumps. They had dressed up to meet me, to make a good impression.

I went out on the balcony for some fresh air. Papa was there, smoking. We didn’t speak. Though it was supposed to be the suburbs of Leningrad, it didn’t look like the suburbs. It looked like the boonies. The sight of rural Russia outside, with its dying grasses and wooden huts and broken roads, was too much for me on my first Russian evening. I needed to continue to believe that our friends were living here well.

We squished around the dining-room table, which was flanked on one side by three chairs and on the other by a low couch, on which three of us would have to sit. I did not want to be one of those people. The couch was so low, I would have to ask someone to pass the food down to me. And I didn’t like the thought of just my head bobbing above the table. I took a chair.

The food, and there was plenty, was served on Ellie’s wedding china. We drank vodka out of crystal shot-glasses and wine out of elegant goblets. For appetizers or zakuski, we had herring, crab and rice salad, smoked salmon, tomato and cucumber salad, radish salad, and lots of fresh white bread. I ate as much as I could and had four shots of vodka, each accompanied by a loquacious toast: one to me, one to Papa, one to the hosts, one to the new generation.

Two hours after we had started dinner, the zakuski disappeared and were replaced by large dinner plates, on which we were served steamed turkey and boiled potatoes with dill. No one could eat one more bite, yet we all did, and washed it down with more vodka.

“It’s very hard for us, Paullina,” Ellie said. “Very hard. I get a pension, and we have to live on that. I used to have a good salary when I was working. It’s hard to get by on just the pension.”

“What about Anatoly? He doesn’t work?”

“No, no, he works,” she said evasively. “He writes scientific papers, he does research for an engineering company.”

“That sounds like a good job.”

She was non-committal. “So-so. He hasn’t been paid in four months.”

To punctuate that, I had a fifth shot of vodka. “Four months?”

“Hmm.”

“So why does he keep going to work?”

Ellie shrugged. “What else is he going to do? Anyway, sometimes he goes, sometimes he doesn’t.”

Ellie said she herself missed going to work.

“Really?” I said. “What was your job?”

It’s not that she didn’t tell me. She did. Her work had something to do with submarines and traveling all over the world. It sounded important and interesting. But I had had too much vodka, and the words she was saying to me weren’t part of my ten-year-old Russian vocabulary. Sometimes I would ask her to repeat a word, but that didn’t help me understand her any better. If anything, it confused me.

Maybe splashing some cold water on my face would help. Standing up shakily, I asked Ellie to point me to the bathroom.

She walked me down the hallway.

“Right in

here,” she said proudly. “If you need to wash your hands, you can go across the hall to the washroom, okay?”

I locked myself in. The little cubicle, three feet by two feet, did not smell fresh. The toilet paper was cheap and rough.

And the flush was not intuitive. There was no handle, no button, no cord to pull. I spotted a series of metal wires. I pulled on one of them several times, and when that failed, I stuck my head outside, where Ellie was waiting in the corridor. She told me to pull the metal wires up. The toilet flushed.

When I had finished, I found Ellie in the kitchen, cleaning up. While I helped her, she continued with her story. She told me she used to get paid a lot, but since she had retired, her pension was only three hundred and eighty rubles a month.

I did the calculations. “But Ellie,” I finally said. “How can that be? That’s only about sixty-four dollars.”

She shrugged. “Don’t you remember how much your mother and father got paid when they lived here? Three hundred and eighty rubles is a very good pension. Your mother used to make a hundred rubles for a full month’s work.”

“Yes. Yes, she did.” I remembered that. I knew that. My mother told me enough times. I wanted to ask how that number translated into today’s rubles.

“Ellie, how do you pay for your apartment?”

“No how,” she replied. “We don’t. We get vouchers. When they pay Anatoly, then we pay rent. We haven’t paid in three months.”

Back at the table, Anatoly asked me questions about my first novel, Tully, the only one of my books so far to have been translated into Russian, and therefore the only one of my books he had read. He wanted to know if the story was true or made up. If it was made up, he asked me how I could make up all those details about Tully, as if I actually knew her.

Anatoly was an aspiring writer himself, as almost everyone in Russia seems to be. His brother Viktor — a poet — kept saying, “Give it to her, go on, give it to her. Why won’t you? You have to. Go on. She’d love to read it.”

Anatoly would ignore his brother for a while and then snap: “Why do you keep going at me? ‘Give it to her, give it to her . . .’ She is too busy. She is an author. She’ got her own work. You think she has time to read it?”

“Read what?” I finally inquired politely.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

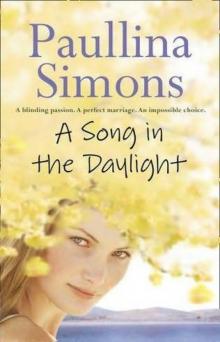

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)