- Home

- Paullina Simons

Bellagrand Page 43

Bellagrand Read online

Page 43

“I’m big for my age, Mama says.”

“Your mother is right. Maybe no lunch for you today then? You look as if you’ve had plenty to eat.”

“Aunty Esther, I’m starving. Zio Salvo always feeds me a lot.”

“Does he? Well, then, I’ll have to feed you even more. Did he feed you ice cream?”

“Two scoops and fudge.”

“I know a place where they’ll give you three scoops, fudge, and whipped cream. Let’s go there now.” Esther didn’t look back as they sped down Mt. Vernon.

Gina and Harry spent the month overheated and buying new furniture. They had left everything behind, even Harry’s favorite malachite table, even the mosaic table he had made himself.

They engaged a charmless but highly recommended real estate agent, who did not wear silk suits or cart small boys around, but who did take Harry and Gina to look at the available properties in the area. Houses were expensive, and nothing was as beautifully located as the sprawling brownstone they had rented. They decided to stay put. Gina found Alexander a playgroup on Byron Street that all the pre-school-age Beacon Hill children attended. It would be good for Alexander to play with other children, and she could make friends with the Beacon Hill mothers.

But in September, when she started taking him, she discovered that the women who brought the children were not the mothers but the nannies. The mothers were at recitals and conservatory meetings, having fundraising lunches, buying art for the Boston Museum, and opening hospital wings. Gina wanted to make friends, but knew socializing with nannies wasn’t appropriate. She looked up her old friend Verity, who had lived in Back Bay, but learned to her disappointment that Verity was back in Lawrence with her husband and seven children. Seven! She had more than enough for a volleyball team. Gina kept meaning to visit her.

A few blocks down Mt. Vernon on Louisburg Square lived a beautiful, vivacious woman named Meredith, wife of a financier and a mother of two, one of them a boy Alexander’s age. She had the potential to be a friend, and Gina made a determined effort to find common ground with the stylish and well-connected woman. She seemed to grasp well the intricacies of the social calendar and the duties expected of a Beacon Hill wife.

The first thing Meredith did was advise Gina to hire a full-time nanny, without which, the young woman said, it was much more difficult to keep to a proper schedule. Big money needed to be spent to make Boston more modern, more literary, more progressive. The symphonies, the concerts, and the lavish dinners were not going to organize themselves. Gina ignored Meredith’s principal piece of advice as long as she could, changing the subject, even laughing it away. “You’re so funny, Meredith,” Gina would say.

“But I’m not trying to be funny, Jane,” Meredith would reply.

“I know. That’s why you’re funny.”

Gina suggested activities she and Meredith could do together with their children, like walking in the Public Garden, or going to the Freedom Docks, parts of which were being converted into an immigrant museum. Meredith would think for a moment. “You mean the two of us, with the children and the nanny?”

“I was thinking without the nanny.”

“Without the nanny? But what if the children need something?”

Gina shifted from foot to foot at Meredith’s front door. “What could they need? Like an ice cream?”

“Well, I don’t know, do I? But I know they need things because Gemma is always fetching one thing or another.”

Gina pulled on Meredith’s sleeve. “Come on. It’s a beautiful afternoon.” Alexander stood almost quietly by her side, holding a soccer ball, every once in a while whispering, “Mom, let’s go, Mom, let’s go, letsgoletsgo—MOM.”

“Darling,” Meredith said with a disapproving glance at both mother and son, “you simply must hire a nanny. It’ll make your life so much easier.”

“My life is not very hard,” Gina said. “All I do is play with my boy.”

“That’s what I mean,” said Meredith, arching her perfect eyebrows.

It took a month for Gina to ease Meredith into the Public Garden for a “quick” walk, fitted in grudgingly before pre-opera cocktails, an invitation to which Gina and Harry had politely declined.

“Why are we going to the Public Garden?” Meredith grumbled. “It’s not Sunday. I’ll walk with you there on Sunday. That’s when all the mothers walk their children, after church and brunch on Sunday afternoon.”

“We can go then, too,” Gina said. “But today Alexander and Walter want to play ball.”

“Darling, please don’t tell me you still haven’t followed my advice to hire someone. Good help is the one true measure of a respectable home.”

“I have a housekeeper, if that’s what you mean. She is very good.”

“That’s not what I mean,” Meredith said, her eyes flicking to Alexander, who was running ahead with Walter and his tag-along toddler sister, Mabel.

Gina nodded. “Trouble is, Meredith,” she said, “it took me a really long time to have my one child, and I don’t want someone else to take care of him. I want to take care of him.”

“But that’s just not how it’s done, darling,” Meredith said. “It’s simply not done. Where are you from?”

“Sicily.”

“Sicily? Really! You must tell Edward. He’ll be fascinated. He studied the African cultures at Brown. He’d love to talk to you about it. When are you free for dinner?”

“Sometimes Harry’s sister takes Alexander on the weekends. Maybe then?”

Harry found Edward an unacceptable bore, and the four of them didn’t get together as often as Gina would have liked.

It was a shame, because Gina really wanted to establish a friendship.

Harry would try to make her feel better. “What can I tell you? Maybe she can get herself a more scintillating husband. If I hear one more word about the taxidermy of gazelles, I’ll taxidermy him. And you—hire a nanny and you’ll fit right in. The ladies of the house do not cook their own meals.”

“Or look after their own children.”

Harry would shrug. “Now, in Florida you stepped all over Emilio’s toes by meddling in his kitchen—”

“You mean my kitchen.”

“He was a good sport about it. But here, it’s not done. The housekeepers will gossip. Their ladies will gossip. And then the men will gossip about me.”

“Better that than another word about antelopes,” she said.

He laughed, catching her in an embrace. “Quite right. But do you really want to socialize with people who need a lesson in geography with their cocktails? You keep trying to explain to them that Sicily is not part of Africa. They’re not grasping it, though.”

“Perhaps it’s the language barrier,” Gina said. “It’s like Babel.”

While Gina settled into their new life, Harry settled into his. He took a long time to apply to Harvard’s doctoral program. They had moved too late for him to attend the fall semester, but he made plans to start in the spring, researching a number of dissertation topics in the meantime.

Their first fall in Boston, he was even-tempered and happy, except for one early morning in October 1922, when he fumed more than usual after glancing at the newspaper.

“Did you see the way they treated her?” he said. “It’s shameful. Just shameful.”

“Who?”

“I thought you’d seen the papers.”

Gina usually got up before Harry and glanced over the news as she made breakfast and got ready for the day. “Obviously not carefully. What happened?”

Harry threw the paper down in disgust and went upstairs. Gina flicked through the front pages. She found nothing there, but buried in the arts section was a short article on Isadora Duncan’s dance performance the night before at the Boston Theater. The mayor of Boston banned Duncan from performing in Boston ever again after she bared her breasts to the public and yelled, “Life is not real here!”

There was something else, too. She had held up a flowin

g red scarf and proclaimed that red was the color of life and vigor. “This is red,” Isadora Duncan shouted. “And so am I!”

“Do you think the mayor is being unreasonable?” Gina asked Harry when he returned downstairs.

“Unreasonable? He’s abhorrent. Where is Alexander? I’m going to the Athenaeum. I want to say goodbye.”

“Still asleep,” Gina said. “You can go and wake him.” She studied her husband thoughtfully. “I didn’t realize you were such an aficionado of Isadora. We should’ve gone to see her perform.”

“Hardly aficionado. Besides, all the tickets were sold out. But the woman comes to our city on tour and the officials treat her with contempt.”

Gina stirred her coffee. “Isn’t she now a Russian citizen?”

“What does that have to do with anything? The mayor is scaremongering.”

“Maybe. But what do you care?”

“I don’t. I just think it’s shameful.” He bent to her for a kiss. “I’ll go wake him. I promised him I’d take him to a soccer game later today. Where are you going to be?”

“Nowhere.” She paused. “I was thinking of going to Lawrence to visit Verity.”

He laughed. “Yes, okay, but on the off chance you don’t go, where can we meet up? I feel I’m close to choosing a new topic. I want to play with Alexander, but I also can’t wait to talk to you about it.”

Harry spent almost a year deciding on his dissertation and thesis. He couldn’t find a topic worthy of his interest. Every morning he left the house all dressed up, as if he were going to work at the bank, and walked up the street to the Athenaeum, just past City Hall, where they had been married. The Athenaeum was the oldest library in the United States, with entry by special membership only. It was not open to the general public. Access to it was one of the perks of belonging to the exclusive Beacon Hill Club. Harry loved going to the Athenaeum not just because the stacks were private, but because the depth of the library’s research materials was profound. He said he had never worked so hard in his life at anything. He spent long days there. Initially he had wanted to choose a topic involving Russian literature or poetry, but Gina talked him out of it. She thought he should stay away from all things Russian. Kenneth Femmer, Harry’s probation officer, wouldn’t approve, she said. Harry agreed.

After a fall and spring of studying, reading, researching, and talking to Gina about his plans, when it came time to apply to Harvard, Harry demurred. A week or two later, he told her he would not be comfortable going there and was thinking of applying instead to another university to get his doctoral degree.

Gina was taken aback. “I thought the whole point was to go to Harvard, your alma mater. Isn’t that what you told me in Jupiter?”

“That’s just it,” he said. “That’s precisely the part I don’t enjoy anymore. I didn’t know I was going to feel this way, but I have too many bad memories of being poorly treated by the economics chair, and by my peers—the people I thought were my friends—and also by the students. Their sense of entitlement is matched only by their arrogance. I’m just not comfortable with the thought of returning.” He shrugged. “Live and learn. I find the place repulsive, to be perfectly honest. I hope never to set foot on that campus again.”

She didn’t know what to say. She said nothing.

“It’s not a problem, Gia. I’m allowed to go to a university other than Harvard while I’m on probation.”

“I said nothing.”

“I just want a different intellectual environment. I want new friends, and respect. A fresh start. I’ll clear it with Femmer. I’m sure it won’t be a problem for me to go to Medford.”

“What’s in Medford?”

“Tufts.”

“That’s where you want to go?”

“Very much. The school has an excellent reputation.”

Gina tried to calculate the distance in her head. “I think it’s too far.”

“Too far from what? It’s not even as far as Barrington.”

“You don’t go to Barrington.” He hadn’t been there once since they moved to Boston.

“It’s not even as far as Lawrence,” he said.

She hadn’t been there once since they moved to Boston.

“I’ll take the car,” he said. “It won’t be bad. I won’t be gone long. I’ll try not to have too many seminars at night.”

“Too many? How about none? And Harry, we don’t have a car.”

He smiled broadly. “We’ll have to buy one then, won’t we?”

Harry applied to Tufts and was accepted. His probation was ending in early 1924, a year early. Harry was glad. He had no relationship with Ken Femmer, an elderly gentleman forty years on the job. He often talked about how much he missed Margaret Janke.

“Because that’s what you want,” Gina said. “Avid rapport with the guards who watch over you.” But what she was really thinking was: the only thing Harry said he missed about the Florida life was Margaret Janke.

They bought a fancy car, a powerful and expensive black Mercedes. They had to rent a space for it, because Boston was now so full of cars that there was nowhere to park on the streets. They found a carriage house, where, barely twenty years earlier, wealthy Bostonians had kept their horses.

Two

BOSTON IS A REMARKABLE CITY. Gina was always exceptionally fond of it. Being in a city—with shops and pavements and parks and people—made for a different daily existence than seeing nothing but water and sky every day, palms and frogs, mangroves and moss oaks, leisure boats, orchids. Not better. Different.

In Boston she enjoyed dressing up her family in their finery and walking through the Public Garden on Sunday afternoons when everyone was out with their children and parasols, smiling, nodding, chatting amiably with one another. The vendors sold ice cream and drinks on Charles Street, and the Park Avenue Hotel served a delicious Sunday brunch. Gina almost didn’t miss Emilio and his comparatively pedestrian preparations. Alexander would run ahead of them, and she and Harry would walk arm in arm, Harry tipping his hat every five minutes, Gina nodding and smiling.

“We are so well trained,” Harry said.

“Like puppets,” said Gina. “Tip, nod, smile, move onward, tip, nod, smile.”

“And yell—Alexander, not too far!”

“Alexander, not too far!”

Tip, nod, smile.

The one thing they couldn’t find common ground on was what church service to attend. In Tequesta, it had been all about the Catholics, and Harry, in any case, wasn’t allowed to leave the house even for weekly worship. So it didn’t matter what Harry wanted, because every Sunday Gina took Alexander with Fernando and a frequently hungover, yet repentant Salvo to St. Domingo Ibanez. But in Boston, the only Catholic church Gina wanted to attend was St. Leonard’s in the North End, and Harry had no interest in going there. If he would attend anything, he said, it would be the Congregational Park Avenue Church. Gina tried attending it. Once. But everything in the service, from the beginning to the non-Eucharist end, was alien to her. “Why don’t they read ‘Our Father’?” she asked Harry as they were leaving.

“I don’t know.”

“Seems odd not to read the Lord’s Prayer.”

“I don’t know why they don’t.”

“Yes, you said. But why wasn’t there a Eucharist?”

“They don’t do that.”

“But why?”

“I don’t know.”

“Yes, you said.”

So every Sunday, Harry would stay home and catch up on his work, and Gina would take Alexander to St. Leonard’s.

Sometimes Esther would come to Beacon Hill on Sunday afternoons to have dinner with them. She was polite, complimented Gina on the house, the furniture, ate like a bird, but ate whatever Italian preparation Gina put in front of her and praised it, played with Alexander, took him to the park, talked to her brother, and then made her leave before Alexander’s bedtime. Civilized and casual. Gina and Harry didn’t once go up to Barrington to have di

nner at Harry’s father’s house that now belonged to Esther.

Gina asked Harry why they didn’t go, and at first he said that Esther’s coming to them was more convenient, which Gina couldn’t argue with, but which also didn’t answer her question. When prodded, Harry admitted he no longer felt comfortable in Barrington. So she stopped prodding, and they never went. Every other Friday afternoon, Esther would have Clarence drive her down to Boston, and they would pick up Alexander and take him back to Barrington for the weekend.

This allowed Gina and Harry to spend time alone, to get dressed up and go dancing, to listen to jazz, to go to dinner at their new friends’ houses. The dancing was enjoyable, more so than the dinners, which Gina would find burdensome, though she couldn’t pinpoint why. In anticipation of the evenings, she would go shopping on Newbury Street, where she would buy beautiful dresses, silk skirts, suede shoes, crepe hats, white gloves. She had her curly, unruly, slightly graying hair colored and styled. Dressed in smart evening garb, off she and Harry would trot, perhaps to Meredith and Edward’s, or to dine with Barnaby, who had just lost his wife to an undisclosed illness and sorely needed some companionship, or to the home of William and Nancy, a fetching young couple, who lived in a house overlooking the Boston Common on Beacon Street, where kings and ambassadors had lived. Gina enjoyed walking downhill to them, though she liked the slog back uphill at the end of the night somewhat less.

But this was the thing: the gatherings and dinners inside the plush and well-appointed homes were less successful in reality than in her mental renditions. The problem was Harry. He would act like such a stick-in-the-mud. While everyone else would buzz with talk about libraries and parks and fall fairs, about industry and economy and politics and the stock market, about who and how much and where and what was good and why and what was going to be good in two months, Harry would sit and palm his glass of wine. When he was asked by the men at the table what he thought of the rising value of real estate, the farm prices, the factory overproduction, Harding’s sudden death, Coolidge’s ascension, or the civil war in Russia, he would mumble—literally mumble—some nonresponse and turn the subject around to the questioner. He did not argue, did not object, did not engage. He was no longer the objection maker; he was the furniture. His doltish lack of participation would occasionally prick Gina into a squall of an unwanted argument instead of half-sober love at the end of an evening.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

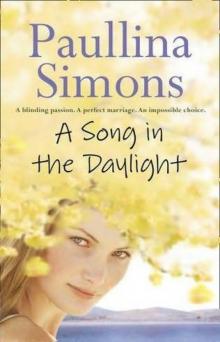

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)