- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Song in the Daylight Page 4

A Song in the Daylight Read online

Page 4

“Some men.”

“Not straight men.”

She laughed. “So not shoes but hair?”

“Yes,” he said. “Hair we notice.”

And breasts. She hoped the sunlight would keep him out of the expression in her eyes. But he said nothing—in that pointed way people say nothing when they’re thinking about things that can’t be said.

“Jewelry?” She was fishing for other things in the water.

“If it’s sparkly, come-hither jewelry, yes.”

Come-hither jewelry! Now she said nothing in that pointed way people say nothing when they’re thinking about things that can’t be said.

He inclined his head toward her; Larissa inclined her body away and pushed her cart forward. “Well, have a great day.”

“You sure you don’t need help?” Stepping away from his bike, he put his hand on her shopping cart. Was he allowed to do that? Wasn’t that like putting your hands on someone’s pregnant belly? Against some sort of Super Stupid food shopping etiquette? “I’ll help you put your 12-pack of Diet Coke into your car. You far?”

“No, no.” No, no was to the help, not the far. He wasn’t listening, already pushing, as she walked next to him, slow. Before she found the unlock button on her key ring, a thought flashed: is he safe? What if he’s one of those…I don’t know. Didn’t she hear about them? Men who abducted girls from parking lots?

And did what with them?

Plus he wasn’t a man.

Plus she wasn’t a girl.

He looked exotic, his brown eyes slanted, his cheekbones Oriental. He looked sweet and scruffy. Who would abduct her from a parking lot? And, more important, why?

And even more important, how did she feel about being abducted?

And was that a rhetorical question?

And furthermore, how come all these thoughts, impressions, fears, anxieties, reactions, flashed in her head before her next blink, like a dream that seems to take hours but is just a couple of seconds before the alarm goes off? Why so much thinking?

And was that a rhetorical question?

She lifted the back hatch and he said with a whistle, “Awesome Escalade. All spec’ed out.” Like he knew.

It took him all of twenty seconds to load her groceries into her luxury utility vehicle. Slamming the liftgate shut, he smiled. “You okay now?”

“Of course, yes.” She was okay before, but didn’t say that. It sounded rude.

He began to walk back to his bike. “Have a good one. And stay away from hairdressers,” he added advisedly. “It’s not like you need it.”

When Larissa got home, she left her bags in the car, left her purse in the car, crashed through the house from back door to the front, limped to the full-length mirror in the entry hall and stood square in front of it.

She wore a lichen parka, gray sweats from college, a taupe torn top. She had not a shred of makeup on her face, and her pale hair was unwashed a day and unbrushed since two hours ago. Her lips were chapped from the cold, her cheeks slightly flushed and splotchy.

Whatever could he possibly mean? She stood in front of the mirror for an eternal minute until she startled herself back into life, and rushed out, Quasimodo-style, to pick up her youngest child from school.

8

99 Red Balloons

While Michelangelo cut and pasted for school, and munched his cup of dry Cheerios, a string cheese, a cookie, a glass of milk, and a fruit cup, Larissa puttered around, looking inside her freezer, realizing belatedly that she hadn’t bought meat. Now she was searching for some ground beef she could hastily defrost for a casserole or a pie. Maybe she could leave Michelangelo with the two oldest; they should be home any minute—

And there they were. The back door slammed, the backpacks thumped to the floor, shoes flew off. They bounded into the kitchen, opened the fridge and…”There’s nothing to eat in this house,” said Emily, slamming the refrigerator door. “Mom, we gotta go. Last week we were almost late to my lesson and I don’t want to be almost late again.”

“Okay, honey,” said Larissa. “I’ll hurry with dinner, so you won’t be almost late again.”

First was cello. Then karate for Michelangelo and guitar for Asher. Mondays were busy.

“Track is starting next month,” said Asher from the back. “I’m joining.”

“Is that before or after karate? Is that before or after band?”

“It’s with, Mom.”

“Is that before or after the orthodontist at five tonight?”

“With, Mom. With.”

Ezra had called when she was out, saying he needed to talk to her, but when she called back he was out and Maggie was cryptic on the phone, saying only that he would talk to Larissa Saturday night at dinner.

When Jared got home, he took one look at her and said jokingly, “Oh, hon, don’t get all gussied up on my account.” Her plain face, her unsmiling mouth didn’t deter him from kissing her, tickling her, from heartily eating the hamburger pie she made, from taking the garbage out, and getting the poster board for Asher’s project on hooligans, from looking at the eight boxes taped and stacked against the bedroom wall and saying, “Whoa. Whoa right there. What in the world have you been doing? Is that why you didn’t answer the phone all day?”

And then it was night and everyone was asleep, everyone but Larissa, who sat in bed, with a People magazine in her lap, staring at her peacefully sleeping husband, the vampire hunter, and the carousel spinning round and round in her head was it will soon be gone and no one will ever know how much she had loved it all.

Chapter Two

1

Things Which Are Seen

The external life is all Larissa knows, most of the time. She married the man she fell in love with in college. She loved him because her friends were either hippie potheads like Che, or sesquipedalian book chewers like Ezra, but Jared had the unbeatable combination of being both, plus a baseball jock. There was something so adorably sporty and cerebral about him. He wore baseball caps and black-rimmed glasses and pitched until his arm gave out, but couldn’t live without baseball, so he got a job teaching English and coaching Little League, and then, according to Ezra, completely sold out and got an MBA, instead of the long-planned PhD in fin de siecle American Lit, but the difference between the two terminal degrees meant that Larissa and Jared weren’t broke anymore, and Ezra and Maggie were.

They bought a gray-colored sprawling colonial farmhouse on Bellevue Avenue on a raised corner lot overlooking the golf course, the kind of house that dreams are made on, the house of twelve gables and white-painted windows adorned with black shutters. Through the pathways and the nooks thirty clay pots sprouted red flowers summer and winter—pansies, impatiens, poinsettia.

Larissa and Jared owned sleek widescreen televisions and the latest stereo equipment. In the game room, they had a pool table, a ping-pong table, an ice hockey table; in the backyard, a heated pool and a Jacuzzi. Their closets were organized by two professional closet organizers (how was that for a job description), and three times a year a file organizer came over to assess their files. Jared paid the bills. He drove a Lexus SUV, she her Escalade. Their appliances were stainless steel and there was marble in their bathrooms. The floors were parquet, the countertops granite, the lights recessed and on dimmers. The sixty windows that needed to be professionally cleaned four times a year were trimmed in white wood to match the crown moldings.

She lived a mile away from Summit’s Main Street, and five minutes drive from the upscale Mall at Short Hills, with Saks, Bloomies, Nordstrom, Neiman Marcus and Macy’s. It had valet parking, sushi and cappuccino, a glass ceiling, and every store worth shopping in.

The children, who were once little and required all her time, were now older and required slightly more. Emily had been the perfect child at eleven, playing championship volleyball and all-state cello, but now at nearly fourteen was exhibiting three of the five signs of demonic possession. The flying off the handle at absolutely nothing.

You couldn’t say anything to her without her interpreting it the wrong way and bursting into tears. The taking of great offense at everything. The disagreeing with everything. She had become so transparent that recently Larissa had started asking her the exact opposite of what she wanted. “Wear a jacket, it’s freezing out.” “No, I’m fine. It’s not that cold, Mom.” “Em, don’t wear a coat today, it’s supposed to be warm.” “Are you kidding me? You want me to freeze to death?”

Michelangelo had manifest gifts of artistic ability. A note from his first grade art teacher read: I think he is showing real promise. He drew a donkey in geometric shapes, even the tail. Kandinsky by a six-year-old. Or was it just his name that fooled his parents into delusions of gifts? Che was wrong about him. He might not have been an angel, with his obdurate nature and single-minded pursuit of his own interests, but he sure looked like an angel, with his cherubic halo of blond curly hair and sweetest face.

No one was particularly sure what Asher did. Today he played guitar, yesterday took karate, tomorrow would run track. Or maybe not. Asher spent every day just being in it, and when it came to New Year’s resolutions he was the one who could never think of anything to write because he would say, “I don’t want to change anything. I have a perfect life.” He was the one who a month ago, at almost thirteen, refused to make a Christmas list because, as he chipperly put it, “I really don’t want that much.” He wanted one thing: an electric mini-scooter. If Larissa and Jared could have, they would’ve gotten him the scooter in every color available, black, lime, lilac and pink. Here, we couldn’t decide which color to get for you, have all four of them, Merry Christmas, darling. The blood of angels flowed through Asher’s veins. He should’ve been named Angel.

Jared maintained Asher resembled Larissa in temperament and looks. Larissa knew: only in looks. Emily, on the other hand, wanted nothing to do with being in any way like her mother, perming her hair, coloring it blue. Larissa was usually impeccably put together; Emily made a point of looking like hardcore indie Seattle grunge. Larissa didn’t play any musical instruments, Emily did. Larissa loved theater, Emily hated it. Larissa frowned for Emily’s sake, but shrugged for everyone else’s. If that’s rebellion, I’ll take it, she said. I’d rather blue hair than grandchildren.

Larissa wished Che could know her children. She missed Che. They grew up together in Piermont, had known each other since they were three or four. Larissa loved Che’s mother, a funny little lady who smoked a ton and cooked great. They were always broke, but somehow Mrs. Cherengue found the money to ship Che’s dad’s body back to Manila. The mother and daughter flew to the Philippines for the funeral. That was fifteen years ago. Larissa was barely pregnant with Emily. She was devastated and sore for years. How could you leave me, Che? What about us living parallel lives? What about us seeing each other every day? What about our friendship?

But Che remained in Manila (“It feels a little bit like home, Lar, what can I say?”), and then her mother got sick and died. Larissa cried for months after she heard. Larissa’s own mother, Barbara Connelly, said, “I hope you’re going to cry like this when I kick the bucket.” That comment went pointedly unanswered.

Che had already met Lorenzo by the time her mother died. So now she lived in Paranaque, without her mother, hiring out her passionate protesting, waiting for Lorenzo to propose and give her a baby, not necessarily in that order.

Che came to her house one morning. I’m in trouble, Lar. I’m in deep deep trouble. Larissa was a senior, Che a junior. Seventeen, sixteen, going on too adult. I’m pregnant.

No. Are you sure?

I’m positive.

Oh, please no. Are you sure?

I’m completely positive. I’m two weeks late. I’m never late. What am I going to do?

Don’t worry. We’ll fix it. Whatever happens.

No, you don’t understand.

I do. It’s bad. But it’ll be okay.

Lar, it’s the single worst thing that can happen to me. Honestly. What am I going to tell my mother? She’ll kill me.

No. Your mother? Never. She’s a sweetheart. And why would you tell her?

Oh, Larissa. My family is not your family. I tell my mother things.

No, not this. Especially not this.

Well, what am I going to do? She’s going to have to know eventually.

Why? I’m serious. Why will she have to know? We’ll go to Planned Parenthood. They’ll help us. You’ll see. Your mom will never have to know.

Planned Parenthood costs money.

Don’t worry. I’ll…I’ll help you. But we have to go there quick. Get a test.

Lar, a test? And then what? I can’t have…I can’t do it. Don’t you understand? I’m not like you. I’m Catholic. I can’t do it.

Well, what are you going to do? You gonna be Catholic, or you gonna be smart?

Why can’t I be both?

Choose, Che.

I can’t. All I know is I can’t have this baby. But also, I can’t not have this baby.

That’s what I’m saying. I’ll get the money together.

How much you think it’s going to be?

Over three hundred dollars.

Che cried. Where am I going to get that kind of money?

I’ll give it to you. I have it. I have it saved up.

How am I going to pay you back?

Don’t worry.

How did you save that much money?

Little by little. Dollar by dollar. Took me four years.

Oh, Larissa.

It’s okay. That’s what it’s for. I didn’t know what I was saving for. But I knew I would need it for something.

I can’t take your money.

To save yourself?

Save myself for the short term, burn in hell for eternity.

Che, you’re not going to burn in hell. Who told you this? Larissa appraised Che, contemplated her. I didn’t know you and Maury went that far, she finally said.

Che wouldn’t look at Larissa. We didn’t. With a fake-casual shrug at Larissa’s startled face. Oh, last month, during spring break, remember Nuno?

No, I don’t remember Nuno!

Yeah, me neither. It wasn’t meant to be. Just a fun few hours.

Maury was Che’s boyfriend, her high school sweetheart. They were going to the junior prom next month. Yet there it was.

Oh.

I know. I told you it’s no good.

You can’t tell this to your mother, Che. You can never tell her.

She’ll know.

She won’t.

God will know, said Che, bending over her hands, on the stoop of Larissa’s quiet Piermont house. They were going to be late for school half an hour ago. It was a sunny morning.

You’ll be fine, said Larissa. You’ll be okay. You’ll see. You can’t have a baby at sixteen. That’s all there is to it. There’ll be plenty of time to have a baby. But we’ve got big plans after high school, after college. We’re going to travel the world. We’re going to go live in Rome and teach English as a second language. Then Greece. We’re going to become tour guides in France, remember?

I remember. But Che was slumped into a fetal position, her backpack on the concrete steps next to her. She looked like a backpack herself, dark and small and curled up. Larissa sat down next to her, patting her back. How could Che have been so careless when she knew what it would mean? When the decision was utterly unbearable, how could she not have taken every precaution and then some? They went to school. And Larissa carried her books, and laughed in the hall, and pretended that everything was as it always was. Only Che’s pallid face by the lockers in between periods was Larissa’s ruthless reminder that nothing was the same.

Later they went to New York University together, where Larissa, a theater major, met Ezra and Evelyn and Jared, while Che, an undeclared major, got busy with her causes: saving the spotted owl, saving the whale—and then her dad had a heart attack and died, and she left the U.S. for good. The girls never did get to Rome

or Greece or become tour guides in France.

Nowadays, without Che, Larissa had lunch with Maggie most Tuesdays, and twice a month with her friend Bo, who worked at the Met in the city, and once a month on Thursday she drove to Hoboken to see Evelyn, whom she loved and envied. Occasionally she took a walk with Tara down the street, who, though married with two kids, always seemed lonely. Larissa walked, while Tara talked, and it suited them both. On Fridays, after she had her nails done and her eyebrows waxed with her young nail friend Fran Finklestein, Larissa wrote Che a short note, like a diary entry, gingerly holding the pen with her painted nails. She told Che of Maggie and Ezra, of Evelyn and her five children, of Bo and her hypochondriac mother and her layabout boyfriend. Bo was the only one working in that household and lately it had been driving her crazy. Che was far away and liked to hear news from home.

When the mail came, Larissa would leaf through the catalogs and the magazines standing over the island in her kitchen. She didn’t read sitting down anymore. She didn’t have time. There was always the next thing, and the next. The phone was always ringing. Evelyn called to ask her what she thought of Marilynne Robinson’s new book (which Larissa hadn’t read, but pretended she was really into because Evelyn was so smart and intimidated Larissa).

Evelyn and Malcolm didn’t watch TV in Hoboken. They didn’t even have a TV! They had two couches, a chair, and a fireplace. And a low long table on which to place the tea cups and wine glasses and the books they were reading. Whenever she and Jared went over, all they did was sit and talk about books. Larissa often held Evelyn up to Jared, who said, “Do you think it’s because they live in Hoboken that they don’t have a television? We lived in Hoboken, we had a TV.” And, “What do you want to do, Lar, you want to get rid of the TV? Propose it, I’ll say yes.”

Evelyn homeschooled her kids. It was incongruous that she had the time, could find the time, could do it. “What do you want to do, Lar?” said Jared. “You want to homeschool our kids? Propose it, I’ll say yes.”

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

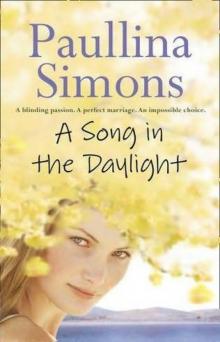

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)