- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 39

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 39

“Mirabelle is too kind,” Snow says. “I’m afraid I’m far from a breakthrough. The identity of the last organism has been eluding me. This summer we’ve had sporadic but intense flare-ups of the dreaded disease all over London, and I’ve realized that I’m no closer to a solution, and even worse, I’m beginning to feel as if I’m running out of time.”

“Everyone is running out of time,” Mirabelle’s father, the amateur horologist, says grimly, to the beats of the ticking clock.

“Pipe down, Jack,” says Aubrey, casting him a reproving glare.

“A real epidemic may be brewing,” John Snow tells Julian. The current medical consensus on cholera is that it’s transmitted through the air, but Snow doesn’t think so. For three years he has strongly believed it transmits through physical contact, but lately he has distanced himself from his own theory. “I’m deadlocked at the moment,” Snow says, dejected.

Julian tries to recall what he’s read about this John Snow. He has surveyed so many topics, tried to commit so much to memory up and down the 19th century, that he can’t vouch for the accuracy of his information. For some reason, Julian feels that John Snow is short on time. He doesn’t know why and can’t recall the details, but it lies on his heart heavy as truth. Is this what Devi felt years ago when he used to talk about Ashton? Some uncertain evil, a malign circle?

Julian tilts forward under the weight of his conscience. If he directs John Snow to the correct answer, he will not be heeding one of Devi’s strongest admonitions. He will not be walking lightly through the past. But to say nothing at all feels wrong.

What does it mean to be human, to be good, to be moral, to be all three at once? It means that flawed beings often must choose between two flawed options. What should Julian do? Stay silent and let death reign, or speak and break the laws of design, which may lead to unintended consequences?

Time is ticking. Julian must act.

“At Bangor,” he says carefully, oh so carefully, “my fellow academics in the field of medicine have been studying the pathogens in dysentery, which I know is not cholera, being both viral and bacterial, but nonetheless, I think they were testing the spread of dysentery by water.”

The doctor, Mirabelle, her parents all stare at him. Charles is not here, or he’d be staring at Julian, too.

“It’s a different disease,” Snow says. “With a different pathology.”

“Of course. I’m just saying, it could be a possibility.”

“What possibility?” John Snow sits up stiff and straight like a closed door that’s about to be kicked open.

Julian pauses and then says, “That the water may be contaminated.”

“In dysentery?”

“In cholera.”

“What water?”

“All water,” Julian replies. “Water you drink and cook with and bathe with.”

John Snow doesn’t move, doesn’t blink, hardly breathes, as if he’s listening to the gears in his head churning and turning.

“No, it can’t be,” he finally says.

Julian shrugs. “You know better than me, Doctor Snow. I’m not a scientist.”

Snow jumps up. The door has been kicked open. “It can’t be! Do you know why? Because a city of three million people cannot have contaminated water running into its homes! You are talking plague, Mr. Cruz.”

The Taylors look up at the doctor, baffled, as if they’ve never seen him so agitated.

“You’re right.” Julian inhales. “Improved sanitation is first. But after that, it will get better.”

“No, no, no, no, no. It can’t be.” The scientist scurries out of the parlor into the hall, to fetch his hat and umbrella.

Mirabelle widens her eyes at Julian. “Were you trying to get rid of him? Well done,” she whispers as they follow the doctor out.

“Aubrey, Jack, excuse me, please,” he says to Mirabelle’s parents. “I won’t be able to stay for supper. I must return to my laboratory.” He bids everyone a rushed goodnight. “Please pray with me that there’s no truth to Mr. Cruz’s awful suggestion.”

“I thought he was praying for a breakthrough?” Julian says to Mirabelle with a shake of his head.

∞

Later that night, after supper and a breathless stroll with Mirabelle under the linden trees down the nearby Langdon Lane, Julian witnesses a first crack in the foundation. From his room upstairs, he hears the rising voices of the three Taylors down in the parlor room. There’s entreaty, denial, even gruff imprecation from Mirabelle’s normally impassive father. The balcony and the patio doors are flung open into the summer night and Julian can hear some of their hot words in the muggy air.

Aubrey: “It’s unconscionable!”

John: “What must you put your mother through!”

Aubrey: “Why do you insist on this?”

John: “And what about…”

Julian doesn’t hear what about, but he hears Mirabelle’s voice.

“He’s not a pawn, Mummy. Leave him alone! Don’t you dare burden him.”

Who is this him she’s talking about? Julian? Is he the pawn? Julian walks out onto the balcony and leans over the railing to hear better.

Aubrey: “Charles says that he will be glad to speak to…” Mumble, mumble.

Mirabelle: “No, Charles must not. And to what purpose? This isn’t a game, Mummy. We’re not children. I gave my word! I’m not going to break my word.”

Aubrey says something about her brother George Airy already having talked to someone, followed by an exclamation and the sound of glass breaking.

Mirabelle: “I cannot believe you! Oh, how you infuriate me sometimes!”

Aubrey: “We infuriate you?”

John: “Leave her alone, Aubrey. It’s useless.”

Aubrey: “What do you think you’re doing to us?”

Mirabelle: “This isn’t about you! I already did what you want. It’s about me and what I want! Why can’t you understand?”

Julian hears footsteps as Mirabelle runs through the house and outside. He steps back from the railing and hides by the blowing curtain. Below on the patio, he hears her sobbing.

He’s flummoxed. Why are they fighting? Why is she crying? What could she possibly want that’s breaking their hearts?

33

Five Minutes in China, in Three Volumes

EVERYTHING IN JULIAN’S LIFE IS THE DEEPEST MYSTERY.

Trying in vain to stay away from her, instead he trails her like a lover.

He picks up the platonic crumbs that remain when the divine is denied him and carries her water. He needs to believe that this time will be different. And why not? She is different. And by keeping himself away, Julian is different, too.

They start their day at dawn with a horseback ride. They end it at nearly midnight in the dining room scarfing down their cold beef and pork pie.

With George away in Wales, Julian and Mirabelle sidestep the Observatory and head straight for New Park Street Chapel to pick up Spurgeon’s marked-up and corrected sermons and head to the British Museum, across town. They pass the time in the long carriage ride across congested London by inventing names of new diseases, making up titles of fake books, and by debating the pros and cons of a new elixir on the market called heroin.

Mirabelle is as solemn a masterpiece as Julian has ever encountered. His breath is perpetually short when she is within his inhale. He says solemn, but he means only in the emotion that she swirls in him, which is as profound a longing as he’s ever had for her. Because in her purest form, the masterpiece is not only breathtaking, and open, and friendly and trusting, but aflame with humor. There is a constant twinkle in her eye, a wry smile at her perfect mouth. The masterpiece likes to tease. She likes to discuss serious things with a light touch, and she likes to be made to laugh.

“I think Barnabus may have arachnid herpes,” Mirabelle says of their driver before they’ve crossed the river. She likes the game of making up diseases that Julian had started.

“How ca

n you tell?” says Julian, squinting and rubbing his chin. “Because of his swollen ankles?”

“Yes, but now that you’ve mentioned swollen ankles, I realize I’ve misdiagnosed him. It’s not arachnid herpes. He’s got thorny tongue.” Mirabelle laughs even before Julian can laugh.

“Thorny tongue? How did you come by this crack diagnosis?”

“Because he also can’t pay attention and he’s got stiff elbows—two sure signs of the malady.”

“Barney,” Julian calls through the half-open front window to the oblivious driver. “Miss Taylor and I are in a quandary. What do you think you’ve got, arachnid herpes or thorny tongue?”

“What?” Barnabus says. “I can’t hear you. Did you say horny tongue?”

“Oh, he’s deaf, too? I take it back,” Mirabelle says. “It must be rooster warts.” She peals with laughter.

As they’re crossing the Thames at Waterloo, they invent some book titles.

“Giants and Swindlers.”

“Turtles Without Faith.”

“Swampy Rebels.”

“Fish in Stockades.”

Charles Dickens apparently has made up some book titles to emboss on the spines of fake books that furnish the nearly empty library of his new home, and this delights Mirabelle, to invent titles like the great Dickens.

They switch topics one more time after they’ve crossed the Strand by the Savoy Palace.

“I don’t know what you could possibly have against heroin, Mr. Cruz. It’s stronger than opium from which it’s made.”

“That’s what I have against it, Miss Taylor.”

“But opium is called God’s own medicine! How can you be against it? Among all the remedies which it has pleased the Almighty to give to man to relieve his sufferings, none is so effective as opium. And heroin, produced in a laboratory with modern scientific methods, is stronger! So, it’s even better. It treats coughing, pain, insomnia, digestive ailments, and hysteria.”

Julian tries to list some of the disadvantages of this miracle restorative. He is met with Mirabelle’s trenchant skepticism.

“What disadvantages?”

“Let’s see. Ferocious addiction. Diminished respiration, a slowed heart, agonizing withdrawals. Sweating. Vomiting. Death.”

“Piffle!”

The hour passes much too soon.

The grand British Museum, recently rebuilt from a mansion called Montague House, stands off Great Russell Street. Nearby, the newly constructed Oxford Street has cut a swathe through the rookery of St. Giles, severing its main arteries. There’s now a shopping quarter where the heart of the slum used to be. When Julian asks Mirabelle if she’s ever been to St. Giles, hoping she will say no, she pauses a moment before replying. “There’s a man in St. Giles I call Magpie Smith,” she says, “who lives under the stairs with his dog. You can’t give him any alms because he’ll spend it on drink, but you can bring him some dinner. Usually he shares it with his mangy cur.”

“And do you,” Julian asks, “bring him some dinner?”

“Not anymore.” She smiles regretfully. “Mummy found out I was visiting him and tattled on me to Father. Now they blame me for Father’s heart incident.”

“Magpie Smith must miss you.”

“He’s comforting himself with gin, I’m sure. You sound as if you’ve been inside St. Giles, Mr. Cruz. It’s much better than it was, you know. Maybe we can go there sometime, and you could meet my indigent friend. My parents might not mind if you’re by my side. Perhaps we can bring him some heroin and see which one of us he agrees with about the elixir’s merits.”

“He won’t be able to give you his learned opinion, Miss Taylor,” says Julian, “because he’ll be dead of an overdose.”

Coventry Patmore, the supernumerary at the Museum, is a skeletal man with sunken eyes and receding messy hair. He appears noiselessly out of the shadows of the research department on the second floor and speaks to Mirabelle in a tone so hushed, even Mirabelle can barely hear him. “Often, I’m reduced to guessing what he needs me to do,” she whispers to Julian. Being a supernumerary must be back-breaking work, because the man looks as if he’s on his last legs. Coventry sets up Mirabelle and Julian with pens and parchment in a small enclave deep in the poetry stacks (“because in his other life, Coventry fancies himself a poet,” says Mirabelle) and they begin. Their job is to transcribe Spurgeon’s marked-up and nearly illegible sermons onto a clean parchment, proofreading and editing the words as they go, and the polished text will then be checked by Patmore before it’s typeset onto printing plates.

“Make your queries quietly, Mr. Cruz,” Mirabelle says, “or you’ll upset Coventry.”

“I have a query, Miss Taylor.”

“Already? But we haven’t opened…”

“If you’re Coventry’s assistant, does that make you the supernumerary’s supernumerary?”

She giggles.

Julian’s eyes are merry. “But since I’m your assistant, does that make me the supernumerary’s supernumerary’s supernumerary?”

She laughs.

Coventry Patmore springs up at her elbow. “Misssssssss Taylor! Have you forgotten where you are?”

“I beg your pardon, Coventry.” She covers her mouth. “Mr. Cruz was being untoward, and I couldn’t help myself.”

“Do better, Miss Taylor. And instruct Mr. Cruz to be toward.”

“Coventry, wait!” Lowering her voice, Mirabelle whispers to Julian, “He is a funny man. Watch.” Clearing her throat and getting up, she approaches the supernumerary. “Have you heard that Thomas Robert Eeles has got hold of some new Charles Dickens titles and is planning to publish them?”

“Oh, that scavenging bookbinder!” Patmore exclaims. “How would he get his hands on them? We publish Dickens!”

“He met Mr. Dickens in a tavern. But don’t despair, Coventry. A friend of mine who was there and witnessed the encounter managed to purloin this coveted list.” Mirabelle opens a torn piece of blank parchment and pretends to study it intently. “We can make Mr. Dickens an offer for some of his new books if you like.”

“Let’s make him an offer for all of them.”

“Reserve judgment, Coventry, until you hear the titles. Here’s one.” Mirabelle pretends to read. “Five Minutes in China, in three volumes.”

Patmore frowns.

“Here’s another. A Catalogue of Statues of the Duke of Wellington. No, let’s have Thomas Robert take that one, that doesn’t sound very interesting. What about Drowsy’s Recollections of Nothing, in four volumes?”

“Miss Taylor…”

“No, here’s one we should publish, though it’s not Dickens. Edmund Burke on the Sublime and Beautiful, in six volumes!”

Once he understands he’s being pranked, Coventry Patmore turns to concrete. “Are you quite finished, Miss Taylor?”

She leans forward and kisses him on the cheek. “I am, Mr. Patmore.”

Julian and Mirabelle sit next to each other at a wooden table between imposing bookshelves. Reluctantly Julian wears the gold-frame spectacles Spurgeon had gifted him. He wishes he didn’t need them, but without them he can’t read a word of the pastor’s script. Wearing glasses makes him look and feel like a teacher, not a boxer, makes him feel as if he is standing next to a blackboard, not shirtless and brawny in the ring. Wearing glasses makes him feel like Ralph Dibny.

The only good thing he can say about it is that Mirabelle doesn’t seem to mind. She smiles at him just the same.

The work is painfully slow. Every few minutes they stop transcribing to discuss usage and punctuation. Sometimes even with the eyewear, Julian can’t decipher Spurgeon’s angry corrections of Nora’s first-draft transcription. Nora transcribes Charles’s sermons as if she is either new to Baptist teachings or new to the English language.

Mirabelle has a soft spot for Coventry. Mirabelle, Julian realizes, has a soft spot for everybody. (Even him?) “Coventry has a wife and four children, that’s why he never stops working. Is it any w

onder he’s so stooped? Emily, his wife, has recently had another child, the poor thing. Even with help, she can barely cope with the three she’s got. I like babies, so I offer to take him to the park some afternoons. Would you like to join me when we’re finished here?”

“If we’re finished here.”

“Here’s the thing you must learn, Mr. Cruz, if you haven’t learned it already. You’re never finished perfecting words, never. Only the Word of the Lord is finished. Everything else is in perpetual need of improvement. I, for one, have many other things to do today than sit here and figure out if Nora meant to write “divine” or “sublime.”

“Either is fine. What else is on your plate today, Miss Taylor?”

“Taking the boy to the park, for one.”

“And then?”

“Can we get back to work, please? The baby is waiting.”

For hours they sit lit by two gas lamps, hunched over the parchment in the musty enclave, their heads together. Her fragrant perfumed hair is near him. Her glowing skin is a hand’s caress away. The sleeve of her jacket, underneath which lies her blouse, underneath which lies her bare skin, touches the sleeve of his coat, underneath which there’s a white shirt-sleeve, underneath which lies his bare skin. Who can pay attention to the semi-colons and exclamation marks when their naked bodies are three types of fabric away from pressing together? Silk on linen, silk on wool. Her coral lips are an exclamation mark, her warm breath an ellipsis.

The sermon they’re working on is called “My Love and I a Mystery.”

Julian fears it’s going to take longer than Mirabelle intends, for not only can they not agree on the correct words in the body of the text, they can’t even agree on the proper punctuation for the sermon’s title. Should it have a colon, a comma, an equal sign or an em-dash? There are only two of them in the poetry stacks and they are of four minds on the subject.

“A colon is not exclusive enough. As if it’s the beginning of a list,” Mirabelle says. “As if my love and I could be a mystery, but could be other things, too, like a play or an outing.”

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

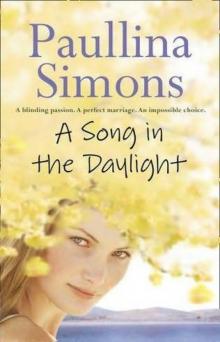

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)