- Home

- Paullina Simons

Bellagrand Page 39

Bellagrand Read online

Page 39

That’s how it ended, the forlorn day Harry’s father was buried. Esther sat collapsed and alone in a chair by the fire, bereaved, hollowed out, with Gina unable to find a word of solace for her husband’s sister except mi dispiace.

Five

HARRY WAS ON THE GRASS by the pool when Fernando brought her home from the train station. Incongruously he was teaching Alexander how to box. At first Gina thought they were dancing, but no. Arms flying out, they were circling each other, one tiny, one large, like two shirtless warriors, skinny and dark, Alexander especially. She’d been gone two weeks, and yet the boy seemed older, taller. He leaped in lion strides to his mother. “Mama, Mama, where you went? Me missed you.” Harry wasn’t far behind.

“I went to Boston on Mommy business,” she said, squeezing his tanned skinny body, kissing his face. “I brought you back a model of a sloop. Maybe you and your dad can build it?”

“Maybe.” He wriggled out of her arms. “Daddy teach me to box. Watch, Mama.” He put up his fists.

“Hold on, buddy,” said Harry, his steadying hand on the boy’s head. “Let me talk to your mom for a minute.” They hugged, they kissed. He poured her some lemonade. “I tried to make it like yours,” he said, “but mine is not sweet enough, though I had dropped a pound of sugar into it. How much sugar do you put in it?”

“More,” she said.

“Well?” He studied her face. “How was it?”

After five days on the train, Gina hoped her face was unreadable, a wan blank. “Not good.” She paused. “Did you call your sister?”

“Yes. She didn’t come to the telephone.”

“Mmm.”

“What? Rosa said she wasn’t feeling well.”

“Quite.” What equivocation! But what else could Gina say? She couldn’t speak about what had passed between her and Esther.

Harry scooted his chair closer to hers. “Why do you look upset?” His hands rested on her legs. “Something happen?”

“I’m not upset, amore mio. I’m exhausted. Happy to be back.” Tilting her head to the sun, she closed her eyes.

He was quiet. “Anyone I know at the funeral?”

She didn’t look at him. “Probably everyone you know.”

Silence from Harry.

“Yes, Ben was there.” Is that what he had been waiting for? “With his very pregnant wife. Baby number four. Hoping for a boy, I think.”

“Ah.” Gina heard the chair scrape against the patio as he got up. “He brought his wife? Esther must have been pleased.”

“Esther was upset at many things at your father’s funeral, mostly the two obvious ones. You should try calling her again.”

“I’ve called her twice a day for a week. Rosa keeps saying she is not well enough to come to the telephone. Did anything happen?” He paused. “I mean anything else?”

Still bleeding from her saber-toothed evening with Esther, Gina shook her head. She feared that every word out of Esther’s twisted mouth had been true. There was no part of it she could relate to Harry. Except, “You should have come, marito.”

“I’m not allowed to leave this house. Why does everyone keep forgetting that?” He stopped speaking, and when she opened her eyes, he was gone, already down by the docks with Alexander. Slowly she walked down to her men. She was tired, whole-body tired, but she wanted to be awake, go swimming, catch a fish. Silently she stood.

“Watch and learn, Alexander.” Harry was circling his son. “Jab is this. A hook is that. Come on, show me you know the difference.”

Alexander rushed up to his father and jabbed him in the ribs with his little fist. “That was a hook, Dad,” he said.

Harry rubbed his sore side. “No, son. That was an uppercut.” He ruffled the boy’s hair. “I’m going to need ten minutes to recuperate.”

“Okay. Me look at my baby gators.”

Harry and Gina sat on the bench by the dock, staring at the water and at Alexander, immersed in the reptile pond up to his elbows.

“I sort of wish he was joking, don’t you?” said Gina.

“Wait until they’re no longer baby gators.”

“Divertente. Grazie.” She smiled the benign smile of the one being comforted. “I didn’t know you knew how to box, caro.”

“Roy taught me. You learn some crazy shit in prison.”

She could imagine.

“Do you want to take the boat out?” he asked.

“Yes, very much. After a bath and a nap.”

“I can help you with both of those.” His hands reached for her arms, for her neck.

They mulled over what to do with their son in the middle of his napless afternoon. “When’s the reading of the will?” Gina asked.

Harry shrugged. “I don’t know. Two weeks. But what does it have to do with me?”

“What do you mean?”

He placed his hand on her hand, leaned over, and kissed her fondly. “I love you. In two weeks, you will know what I mean. Alexander! Hey, bud, would you like to have a nap? Mom and Dad are going to have one.” He kissed her again. “A sleepless one.”

Esther did not call before, during, or after the reading of the will. It was opened and read, and the details of it appeared in The Boston Globe, which was delivered by subscription a full week later. Aside from the Palm Beach Gazette, that’s how they had read the news for three years. On a seven-day delay. Herman Barrington left half of his estate to Esther, as well as his main property in Barrington, his secondary property in Newburyport, all his cars, his two boats, and all his material possessions. One quarter he bequeathed to the cardiac unit at Boston Memorial Hospital, which had kept him alive an additional decade, gave it in memory of Elmore Lassiter, Esther’s husband and a cardiologist. The rest he distributed between the various charities supported by Esther’s foundation. Herman stipulated that until such time as the boy didn’t need it anymore, Esther would provide for Alexander’s education, and only his education. To Harry he left nothing. He didn’t even mention a son by name, as if he didn’t have one. The only reference that might have alluded to Harry was the cryptic coda: “Blessed are those who expect nothing, for they shall never be disappointed. That is the ninth beatitude.”

“Is that for you?” Gina asked. “The last part?”

Without reply Harry poured himself the last of the fresh-squeezed orange juice.

“It is!” she exclaimed, remembering. “It’s from before. When we first met, you and”—she decided not to say Ben’s name out loud—“how you bickered over the meaning of those words. Oh, Harry.” What had she done? What had they done?

He smiled. His gray eyes were clear, not occluded. He seemed at ease, perhaps at false ease, but she couldn’t be sure. “Gia, I’m not upset,” he said, “precisely because of Alexander Pope and his ninth beatitude.” He took out a knife to cut some more oranges. “I know my father.” It was a while before he spoke again. She watched him use the hand juicer to squeeze out the orange halves. “I expected nothing. I deserved nothing. I’m not disappointed.”

“Why do you say you deserved nothing? You’re his only son.”

Harry waved her away. “You are so Sicilian.”

“This isn’t Sicilian. This is fathers and sons.” She stood away from the counter, and from him.

“Not this father and son.” He was busy with the oranges, as if he weren’t paying attention.

“But I don’t understand.” She started pacing the kitchen. “You were getting along so well. He was happy.” She wrung her hands.

He eyed her affectionately, his own hands covered with pulp. “Gia . . . you’re so adorably overwrought.”

“What about your legacy?”

“What legacy? The business our family had built and my father expanded was given to Uncle Hank’s sons. They’re in charge of it now. How do you think my father felt about that? That his brother had sons who carried on with the century-old family business, while he had a son who sat in prison? He and I couldn’t even talk about it. Oh, sure, we talke

d of other things. Sheds and chairs, Alexander’s gators and boats. John Reed. This house. But that’s all secondary, isn’t it, to the heart of the matter. Which is—I turned my back on my father. That’s how he felt, and there is no getting around that. He behaved exactly as I thought he would.” Harry nodded. “I respect him for that. I would’ve been ashamed to receive profit from the fruits of his lifelong labors, after I had been so dismissive of his work.” He sounded nonchalant and remorseless. Gina wanted to call Esther and demand to know why she didn’t hold her brother to account for anything. Why was a woman the only one blamed, never the man?

“My father knew my apathy to his money,” Harry went on, “and then my antipathy. I always let him know it.” He threw away the scraped-out orange halves. “I’m hungry. Can you make us some eggs? Maybe a frittata?”

Dejected, she trudged to the cabinet to get out the pans. “Will your sister help you?”

“She won’t even take my calls.”

“You should have gone to the funeral, Harry,” Gina repeated, a refrain of shame.

“I think it was too late to change the will by then, don’t you?” Harry said. “Father was already dead.”

“That’s not funny.”

They stood without moving. They stared into each other’s faces.

From across the kitchen Harry spoke to her. “Gina, you pay a price for where you stand. I keep telling you, but you refuse to listen. You and I made our bed long ago. We picked our place. We said we would not live my life, nor your life, but a new life.”

“We certainly didn’t live your life.” She lowered her head. “Until now.” Though they had lived plenty of hers. “But you grew up with something that I never had.”

“Which is?”

Gina tried to define it. What was it that his rejected wealth gave him—in one word? “Freedom,” she said.

“You mean slavery,” he said.

One of them had to move out from the impasse. It was always her. “I guess it depends where you stand when you cast that vote.”

“I suppose so.”

She knew he said it to end the discussion, not to give her opinion weight. Frowning, she stepped back into the ring. “But Harry, slavery is what you called my having to work every day to pay the rent and feed us. Remember that?”

He frowned in response, back in the ring himself. “So?”

“How can both opposites be defined by you as one and the same? I worked to eat. You refused that life. But you didn’t have to work at all, except at what you wished. And you refused that life, too. How can both be slavery? Besides these two choices, what else is there?”

He stood and was silent, except for a sharp, knowing shrug. Why did Gina feel it wasn’t because he didn’t have an answer, but because he had an answer he didn’t want to share with her?

She waited for him to speak, and when he didn’t, she opened her mouth and spoke. “Until recently I didn’t even know what it was that you took completely for granted. What you had turned your back on.”

“My back may have been turned, but what was my face looking at?” He pointed to her.

“I don’t know if we had thought it through.” Her shoulders slumped.

“I want to say two things in response. One, I hope you didn’t marry me for my money.”

“I would have been a fool to.”

“Indeed. And two, don’t fret so much. We have not been left with nothing. This isn’t like before.” He opened his hands to the lawn and the sky and the gleaming waters. “We have everything we need. This is where we stand, the price of our marriage. To live in paradise by the sea. And soon I’ll be free.”

“Yes,” she whispered, gulping for air. Why did her throat suddenly constrict, why did she find it hard to breathe? Free or in slavery?

Chapter 14

SPANISH CITY

One

HARRY BARRINGTON, I CAN’T believe I’m saying this, but I’m proud of you.”

“I can’t believe you’re saying it either. Would you like some wine to celebrate?”

“I’m working, so no. But you go ahead.”

“You want me to drink alone? Nice. Do they allow you to have orange juice on the job?” He poured her a glass. “We have the groves right here, out back.”

She drank and praised it. “Delicious. So fresh. I’m going to be truthful, Mr. Barrington. I didn’t think you’d be able to do it.”

“Grow oranges? It’s not that difficult.”

“Stick it out. Keep to the program. Behave yourself. Alter your thinking.”

“Perhaps less truthful might be a better approach?”

“I really thought you were going to fail. I expected you to fail.”

“Um—I’m sorry I let you down?”

“You surprised me.”

“Pleasantly, I hope.”

“No question. I’m sure your family is relieved.”

“I hope so. I don’t think they wanted me to fail.”

“Oh, I didn’t want you to fail. I just expected you would.”

“O ye of little faith.” He smiled.

“Well, never mind that. Here we are. The moment you’ve been working for. And you really have worked hard. You were exemplary. You were upfront with me, you broke no laws.”

“That you know of.” He kept a straight face.

“You were always here, where you were supposed to be, and even when I made unannounced visits, you welcomed me.”

“You were the entirety of my social circle, Officer Janke. Frequently your visits were the highlight of my week.”

“Sometimes I can’t tell if you’re joking with me, Mr. Barrington.”

“I would never joke about a thing like that.”

“Well, good. Because I enjoyed getting to know you, and getting to know your family.”

“And they you. My brother-in-law Salvatore especially.”

“Really?” Janke leaned forward and lowered her voice. “I must admit something to you—I’ve never liked him. But please don’t say anything.”

“I would never.”

“He seems shifty to me.”

“You don’t say.”

“Unlike you. With you, what I see is what I get. I wasn’t so sure in the beginning. But I am now.” She closed her book. “There are many decisions before you,” she said. “Big decisions. After all, now that you can go anywhere, and do anything, you have to decide where you want to go and what you want to do.”

“You are right, that is a big decision indeed.”

“But a rewarding one. On the one hand you can be like that brother-in-law of yours, jumping like a bean from one rock to another . . .”

“Yes.”

“Or you can be like your father—a rock until the end, for other people to jump on.”

“People other than me.”

“Or you can be somewhere in between.”

“A new thing perhaps?” Harry smiled.

“Yes! A new thing.” She got up to leave. “Just remember: without work, man has no meaning. Life has no meaning.” She collected her papers. “So what’s the first thing you’re going to do as a free man?”

He rolled his eyes. “Apparently I have plans to take my wife and son to the market. For three years they’ve been telling me what I’ve been missing.”

“They’re right, it’s wonderful. You’ll enjoy it. If you go next week, it’ll be better. A carnival is rolling into town for a few days. Your son will like that.”

“Perhaps we’ll go again. Because I don’t think that boy can wait for anything.”

They both glanced outside on the lawn, where mother and son were playing volleyball, or as it was called in the Barrington house, go-in-the-bushes-and-get-the-ball.

“Please be careful. Keep to yourself. Stay away from trouble. Probation doesn’t mean you can do what you like.”

“Of course not.”

“Probation means you are no longer bound by the walls of this house. You can go where you please. Except to Commun

ist Party headquarters.”

“And who’d want to go there?”

“Exactly.” They shook hands. “You’re going to do well,” said Janke. “Whatever you choose to take up, I’m certain you will be very successful at it.”

“Why, because of the way I’ve navigated the terms of my prison sentence, Officer Janke?”

“Precisely, Mr. Barrington. You learned to live inside the box. That’s very important for all adult men to learn. Just look at your brother-in-law for the other example.”

“He’s not an adult yet, that’s why. Goodbye, Inspector Javert.”

“You’ve called me that several times over the years, Mr. Barrington. You do know that’s not my name, correct?”

“Yes, Margaret,” said a smiling Harry. He opened the heavy front door to let her out. “I hate to admit it, but I’m going to miss you. Your little pronouncements, your hectoring nature, your prim coda. I don’t meet someone like you every day.”

“Well, perhaps then, we can arrange for you to keep seeing me, Jean Valjean.” She walked down the marble steps, with a jaunty backward wave.

Harry laughed. “So you are human!” he exclaimed. “All these years, I wasn’t sure.”

And so for the first time in three years, the three of them piled into their Packard. Gina drove them across the water to Tequesta, where they parked and strolled among the friendly folk, while Alexander ran ahead through the market in the waterside park. They could barely keep up. At the produce stalls, the vendors all knew him; they gave him mangoes, and candy, and cakes, and toys. He returned to his parents with arms full of things, which he dumped at their feet.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

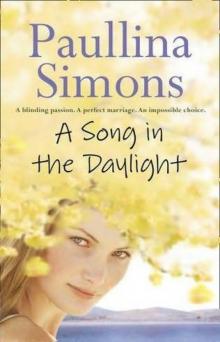

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)