- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 37

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 37

“Julian, you’ve met my brother, George Airy?” Aubrey says, as the astronomer appears in the front hall with papers under one arm and a walking stick in the other.

“Hello, Mr. Cruz, a pleasure to see you again,” Airy says. “You were delayed? Because it took you over four hours to make a trip that usually takes forty minutes.”

Mirabelle intervenes. “We went to the Crystal Palace, Uncle George. To attend to that matter I told you about.”

“Oh yes.” Airy is neutral. “One removal of a papier mâché leaf from a sculpted genital takes how long?”

“About one minute per a set of genitals. Sometimes it required extra effort if I used too much glue.” Julian stands by her side. They do not glance at each other as she speaks.

“Yes,” Airy says. “And there are eighty statues in the transept. That’s eighty minutes. And you’ve been gone four hours.”

“Are you counting the time it takes to get down from the ladder and walk to each one and refill the water bucket as needed?”

George Airy nods. “You’ve always tried to be an efficient girl, Mirabelle. I’m sure you didn’t mean to dilly-dally.”

“I don’t think I did dilly-dally.” She turns to Julian, in her family hall, in front of her uncle, the Astronomer Royal of all of Great Britain and Scotland and Ireland, and says, “What do you say, Mr. Cruz? In your opinion, did I dilly-dally?”

“No, Miss Taylor, I did not see any dillying—or dallying,” says Julian. “You were industrious and efficient. I don’t believe anyone could’ve done the job faster or worked harder than you.”

“Thank you, Mr. Cruz. I suppose I was the right woman for the job. It was an enormous undertaking, though, don’t you agree?”

“Yes, Miss Taylor.” He will not repeat the word enormous, no matter how much she is daring him to. They’re in her house!

“Well, no use standing around like giraffes,” Airy says. “Mr. Cruz probably would like to rest after all that exertion you put him through.”

“Oh, I’m fine, sir,” Julian says. “Miss Taylor did most of the work.”

“I did, Uncle George. He just carried my water.”

“Oh, I’m sure he did, child. I’m sure he did.”

∞

Julian is shepherded upstairs to the best room, a spacious chamber with a balcony overlooking the expansive grounds that stretch into the sloping hills. In the room there’s a four-poster bed, a couch, a dresser and washbasin, a walnut credenza, and wide low-backed mahogany chairs. It’s possibly the nicest room he’s ever stayed in. The effusive welcome Julian has received is above and beyond any normal welcome given by decent people to a stranger who’s arrived with their only daughter hours late and without a suitcase. It’s baffling.

He is brought a tray with tea and biscuits, given clean towels, hot water, new candles, a quire of parchment, pen and ink, slippers in case his feet get cold, and a cashmere-lined silk bathrobe. For a few bewildered minutes Julian sits out on the balcony with a cup of tea, nibbles on a digestive, and digests what’s been happening as he stares out onto a glen framed with a wood, fields of flowers, and riding trails. There are gardens and low stone walls and gazebos for relaxation. In the far distance there’s a lake. On the nearby pond glide black and white swans.

They had such a good afternoon together. They had fun. There is nothing Julian wants less than to leave. He starts berating himself for his irrationality. What’s the point of leaving her house and staying somewhere else? How far would he really go, anyway? He’d be watching her from a local inn or from a hired carriage. He’d be following her, pacing behind her, secreting himself in the bushes, biding his time, silently brooding. Just as he did in the rookery. Well, been there, done that. Time for something else. Why not relax about it, stay at her house, as he wishes, as they all wish, and watch over her from two doors down the hall? Seems so much more practical. And more convenient. And it’s safer for her. If she gets into any trouble, Julian will be here to intervene. Really, Julian concludes, his staying at Vine Cottage is for her protection!

There’s a soft knock. Mirabelle peeks in. “Are they treating you well?” She smiles as she approaches the balcony. “Are you enjoying the view?”

“Yes, it’s beautiful here.”

“Isn’t it? I’m blessed to grow up in a place like this.”

“Yes.” He is too full up to say more. Last time he felt such pity. This time he feels only relief. Why do they both feel like pain?

“Mummy sent me in to ask if you’d like anything else—anything at all, is how she put it. I said, Mummy, I’m not his maid. She told me it was just good manners.”

“You and your family could not be treating me any better, Miss Taylor.”

“Mummy would like me to show you the rest of the house. We have a few minutes before supper. Uncle George informed me we have forty-seven minutes before Charles and Barney return and drinks are served. Would you like to change first—perhaps into that cashmere bathrobe? I apologize, I forgot to tell my family you’re not seventy-two.”

“Perhaps, like you, they think I’m Charles Spurgeon’s father.”

“I still don’t understand why my small joke piqued you, Mr. Cruz.”

“I was not piqued, Miss Taylor.”

“Ah.”

At Vine Cottage, the rooms are light-colored with neat clean lines. Instead of stone or wood floors, hand-knotted carpets from the Ottoman Empire cover the parquet nearly wall to wall. The house is delicately Victorian, all cream ceramic candlesticks and brightly colored curtains. Mirabelle is especially proud of the gas supply that’s been recently piped in to Vine Cottage. She says it’s changed their life.

“And what a good life you have here,” Julian says, incapable of hiding his happiness that this is so. He thanks God that her soul doesn’t remember the rookery of St. Giles at all.

But there is something unsettling about the otherwise ideal home, something that’s been bothering Julian since the moment he walked in. It’s almost like an unwelcome pressure of the intrusive metronome when you’re first learning the piano.

Ah, yes! The metaphor has led him to the truth. It’s the ticking clocks. In every room in the house there’s a longcase clock, a dozen pendulums swinging to and fro, tick, tick, tick…anvils to the heart. The clocks themselves are a metaphor for the actual truth. Merciless time waits for no one.

They have supper in the dining room, around a table lit with candles and set with china under a bronzed gasolier with glass shades. Except for the clock in the corner, hammering every quarter hour, it’s homey and comforting. Mirabelle has been placed by his side. It spares him the need to hide what he feels every time he looks at her, and yet allows him to be bolstered by her proximity. He eats with his left hand, so his right can remain near her elbow.

They’re served herring and boiled potatoes, marinated eels, cabbage and some liver with onions, everything dripping with hot butter. There’s ale and gin and wine, and for dessert, bread pudding soaked in brandy. Spurgeon is a boisterous conversationalist, and not above an occasional ribald remark himself. Everyone’s regard for Mirabelle is apparent. But the attention is trained on Julian—dare he say, single-mindedly? They want to know whether his family came from the coal mines, whether he is the first one of his generation to attend university, what he thinks of living close to the sea, whether he is permanently stationed in Bangor or would he consider a relocation if a suitable position became available in, say, London. He answers their questions as best he can, making up the details of Bangor College, inventing one of the courses he teaches (The Comedies of Shakespeare) and foolishly mentioning his unfinished research into Thomas Aquinas. It’s a good thing he stipulates unfinished. Charles Spurgeon, clearly somewhat of an expert on Aquinas, launches into a monologue on the differences between the Thomian and the Calvinist philosophy on Christ, which allows Julian to shut up and finish the pickled herring on his plate.

“I simply don’t understand why Aquinas rebels against sover

eign election, do you, Julian?” Spurgeon says. “To me it’s one of the most welcome truths in the whole of Revelation. How can your heart not dance with joy to know that the Lord has chosen you to love him?”

Julian swallows the fish. He is of a different opinion on the subject, though he doesn’t want to argue in front of Mirabelle. But since at its heart, the disagreement is about Mirabelle, he cannot keep silent. “How can love, any love, but especially God’s love, be received by compulsion?” Julian asks Spurgeon. “Can love compelled even be called love? If grace is a gift, as in something that’s given freely, one must be free to receive it, yes. But then one must also be free to reject it.”

“What fool would reject God’s grace?” Spurgeon says. “A fool who’s not worthy of it, that’s who. No, the human being does not obtain grace by freedom. It obtains freedom by grace. Do you disagree?”

“Respectfully, yes. I prefer persuasion rather than compulsion.” Julian smiles to soften his words. But there is another thing, too, that Julian agrees with even less, especially given the life he’s been living. Rather, another thing that he wants to be true least of all. “If you obtain grace through no act of your own,” he says, “doesn’t that also mean that you might not obtain grace through no act of your own?”

“Of course it does!”

“But doesn’t that mean that no matter what you do, you could be condemned from the start?” Julian says. “No matter what you do, how you act, how hard you try, there is nothing you can do to achieve a different end for yourself? No matter how you live your days, the end will be the same?” Julian shakes his head. He’d rather have his weak will, a thread of hope, and oil in his lamp. He’d rather have anything than a foreordained future.

48 dots to go.

He is rescued from further argument by Lena the housekeeper, who enters to whisper to Aubrey that there are people at the door. Aubrey throws a frantic glance at Spurgeon, who says he’ll take care of it and leaves the table. The remaining voices die down as everyone strains to hear what the pastor is saying to the visitors and who they might be that they are not welcome at the convivial get-together at the Taylors’ on a Friday evening.

“Is that Pippa’s voice I hear, Mum?” Mirabelle asks. “And her mother’s? You don’t want to invite them in?” She lowers her voice. “What have they done?”

“Nothing, my darling. I’m in the middle of a little spat with dear Prunella.”

“Ooh, I like spats. What about?”

“Nothing important.” Aubrey folds and refolds her napkin. “I would just as soon not see her at the moment. It’ll iron itself out. A few days. Possibly a week.”

Turning her head, Mirabelle widens her eyes at Julian as if to say she has no idea what kind of espionage her mother is up to.

George Airy, who is indifferent to gossip, studies his pocket watch. “It will take me 38 minutes to get home,” he says. “If I ask Barnabus to hurry, perhaps 32. I must dash. Tomorrow morning I’m leaving for your neck of the woods, Julian, for Wales. Before I go, would you care to have a cigar with me outside?”

In the garden, the astronomer lights two cigars. The men puff silently, leaning over the railing, smelling the moist greenery of the fresh night air.

There is great comfort in knowing Airy won’t be long in getting to his point. The man is on the clock.

“What exciting thing is happening in Wales?” Julian asks. The sky is especially beautiful tonight, lit with a billion stars. George Airy is not impressed. He doesn’t look up.

“I’m close to final revisions on my formula to measure the mean density of the earth,” Airy replies. “I’ve been working on it on and off for over twenty years! At last I’ve found a mine deep enough to prove my hypothesis. In Wales, of course, where you have the deepest mines, but you must know that. It’s 1,256 feet deep to be exact.”

“Twenty years?” That seems inordinately long to devote to a single endeavor.

Airy shrugs. “I’m a servant of the Admiralty first and foremost. They don’t care a whit about the mean density of the earth. They do care about the declination of the planets. On comes the star,” George Airy says with a smile, finally looking up at the sky, “without haste and without rest until it reaches the gleaming threads of my eyepiece. All that’s left to do is measure its position with the utmost accuracy. But in the mines, something else is required of me. I like that. That’s why I’ve kept at it. I believe I’ve had a breakthrough at last.” With a cigar in his mouth, Airy produces from his pocket a small metal ball fastened to a string, a portable pendulum. He swings it in front of Julian, back and forth. “I’m about to prove,” he says, “that the pendulum swings faster at the bottom of the mine than it does on the surface of the earth. Which means that the gravitational pull on the pendulum is greater the closer we get to the earth’s core. I’ve found a mine deep enough where I can finally measure by how much. And the difference between the movement of the pendulum between the two locations is going to be part of my formula. Isn’t that exciting?”

“It is,” Julian says. “And it has tremendous implications for the future.” He pauses, thinking of himself, and of time dilation and his own space-time curve that’s affected by one Mirabelle Taylor as if she is the gravitational constant pulling at Julian’s core, even when his time beats faster or not at all. “This research flows from your pendulum work on the Clock Tower? That should be finished any time now?”

“Yes!” Airy exclaims, eyeing Julian with approval. “You know quite a lot about my work, Julian, I am most heartened by this. Yes, everything I do keeps coming back to time and gravity. I don’t yet know how the two are connected.”

“I would say inextricably,” Julian says. In twenty-five years Albert Einstein will be born.

“All I know is that the best clockmakers in Britain said a pendulum clock accurate to within one second could not be built. Do you know who finally said it could and then designed it?” Airy chuckles. “Besides me, that is. Two lawyers! It’s true. One of them is my good friend Edmund Beckett, and the other is Mirabelle’s father, John Taylor. Clock-making is his hobby. He’s a cantankerous fellow but an expert horologist.”

“Perhaps it’s the study of time that’s been making him cantankerous,” Julian says.

“You are most correct. The entire period he’s been a horologist, he’s been in a foul mood. But we needed someone like him—he wouldn’t take no for an answer. Mirabelle inherits that quality, I’m afraid. You wouldn’t think it from looking at her, but she is a willful girl. Anyway, I showed John and Edmund why an escapement must be part of any turret timekeeper, and that has made all the difference in the accuracy of the Great Clock they’ve designed for Westminster. Do you know what a gravity escapement is, Julian?”

Julian knows about escapements of all kinds. “It’s what allows the extra energy that causes over-winding and inaccuracy to flow out of the swinging pendulum,” he says.

“You are a clever man. Yes. The Great Clock of Westminster will have a three-legged gravity escapement.”

Mirabelle’s father helped build the Great Clock. Julian is reeling.

Go take a gander at Big Ben. Go stand there for an hour after a new moon, and see how many people gather around you, holding talismans of the dead, trying to step through the swings of the 700-pound pendulum, between the tick and the tock. You will see them trying to do what you have done.

“But I didn’t call you out here to talk about time, my boy,” Airy says. “Even though if you and I had a little more of it, we could have ourselves quite a discussion. Instead I wanted to tell you about a spring long ago when I met the most beautiful girl. Yes, once upon a time I was young and fell in love, too. It feels like yesterday.”

Fell in love, too?

The man nods, puffing on his cigar. “I knew after two days that I wanted to marry her. So I proposed.”

“Two whole days?”

“I knew what I knew. Richarda was going to be my wife. Her father, however, had other ideas.�

��

Julian chuckles.

“You laugh, and others did also. Her father. My friends. My parents. My sister Aubrey, God bless her. But I was not to be dissuaded from what I knew was an incontrovertible truth. I didn’t have a position or any income to support a family. So I went to work on those things. I received my degree from Cambridge. I became a professor. It took six years, yes, that’s right, Julian, six years, but her father finally gave us his blessing. We were married in 1830 and here I am, twenty-four years later, telling you about my wife and the mother of my six children.”

Julian inclines his head in respect—and confusion.

“What is the moral of my story?” Airy says. “That you are in much better shape than I was. For one, Mirabelle’s father will not stand in your way, I promise you. You will not have to wait six years.”

Julian blinks. “What?”

“You won’t have to wait six weeks.”

Six weeks? “What?”

“Second, you’re already a professor.”

“Sir—uh—you misunderstand…”

“Oh, I don’t think so,” says Airy. “Observation is my life’s work. Well, observation and keeping records, but observation first, since something must be observed before it can be recorded. Something must already exist, Julian, before it can be written about.”

“Yes, sir, but—”

“I would not have noticed it if it didn’t already exist. You were nearly invisible to me in the Observatory until Mirabelle stepped into the room.”

Julian bows his head. Wow.

“Mirabelle is a lovely girl,” George Airy continues. “Well, I don’t have to tell you. She may not be in the first flush of youth, being nearly twenty-six, but don’t let that stop you. Do what your heart tells you.” The stooped man raises two fingers in the air. “Two days is what it took for me.”

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

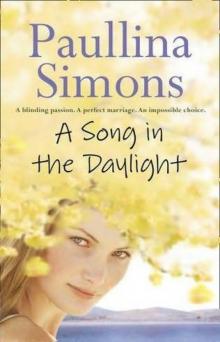

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)