- Home

- Paullina Simons

The Tiger Catcher Page 34

The Tiger Catcher Read online

Page 34

“I care not one whit for angels and flying machines,” Mary says.

“But you know who might care? Josephine. Josephine and her flying machine.” Julian smiles. “Come Josephine in my flying machine,” he sings, “up up, a little bit higher, to where the moon is on fire.”

She is unmoved. “I don’t know why that deserves a smile,” she says.

Julian persists. Philip Henslow who runs the Fortune is an old friend (a brand-new acquaintance, he means), and the theatre is walking distance from her house. Over her relentless derision, Julian tells her that Two Gentlemen is perfect for her, since it’s about a girl who dresses as a boy.

It’s rated poorly, Mary argues. It’s considered by many intelligent people, “outside of Wales,” to be one of the bard’s worst.

They bicker pleasantly as they ride. It’s not terrible, Julian says. Yes, it’s immature, but it’s a comedy. It’s funny. It makes people laugh. The audiences love it. Lance and his dog Crab bring down the house. “Wouldn’t you like to make the people howl with laughter, Lady Mary?”

What’s the stupid play about, she asks grumblingly.

“It’s about two best friends,” he tells her, “Ashton and Julian.” He smiles. “I mean Valentine and Proteus.” Valentine wants to go to Milan and asks Proteus to go with him, but Proteus is in love with Julia and refuses. When he is forced to go anyway, he and Julia swear eternal love to one another. Of course, in Milan Proteus instantly falls in love with another girl. Meanwhile, Julia dresses as a boy named Sebastian and travels to Milan to win back her lover. “You could audition for the role of Julia,” he tells Mary. “It would be a wonderful role for you. Even so, you’ll need to get your mother to agree. I could maybe help you with that. It won’t be easy. But it will be easier than the Globe.”

Mary remains outwardly unpersuaded. “You think you’re clever,” she says. “But I’m cleverer than you. I don’t need your help. I’ll figure something out. You’ll see.”

***

Julian sleeps like the dead and is awake at dawn. First thing he does is check on his growing seedlings. It has rained overnight, and the ground is sopping wet. Because of his efforts, she will have beautiful flowers for her wedding.

He spends the afternoon mixing clarified suet with potash and dipping thick braided twines into it. He dips, lets it dry, dips, lets it dry. It’s painstaking work and it takes up his entire afternoon. He is hidden away in the buttery, busy with this monotonous task. But without his labors, come end of June, there won’t be enough light for the betrothal of his beloved to another man. Black humor. His right side aches from the repetitive movement of his right arm moving the hardening and enlarging candle up and down into the tallow, up and down, up and down.

He looks up from his throbbing reverie—and Aurora stands in the doorway, wringing her hands. She exhorts him to continue as she approaches. “I know you have much to do, Master Julian,” she says, “but I need your help with a delicate matter. I hope you don’t mind the personal nature of my request.”

Welcoming the opportunity to rest his limb, he wipes the warm wax off his hands, and they step outside for a stroll in the gardens where Krea can’t hear them.

Aurora begins by returning to the story of Mary and Massimo. Julian tells Aurora not to fret, that it wasn’t Massimo Mary wanted, it was what he was offering her—which was freedom. Lady Collins looks genuinely perplexed as if she doesn’t know what Julian means by the word freedom. “But some weeks after the man left, she started to feel very poorly. She took to her bed. We almost lost her, Julian!”

“Please—don’t tell me anymore, Aurora,” Julian says, slowing down and glancing at the house, wishing for Krea’s interruption. He doesn’t want to hear it.

“You’re right, of course, I shouldn’t be telling you this. I’m merely pointing out,” Aurora says, “that I don’t want to take away another thing she wants. I need her to marry Lord Falk at the end of next month without fuss.” She informs Julian that yesterday Mary confessed to a lie. Apparently, she wasn’t visiting with her friend Beatrice as she had told her mother. “She says she and Beatrice sneaked off to London together, so Mary could audition at the Globe! She chopped off her hair, Julian! Her glorious beautiful hair! I got the vapors when she showed me. It’s hideous, simply hideous. I said to her, what’s Lord Falk going to say when he finds out on his wedding night that his bride looks like a little boy?”

“And what did Mary say?”

“Well, she is an impertinent trouble-maker is what she is. She asked if I was certain Lord Falk didn’t prefer little boys.” Despite herself, the mother chuckles. “Sometimes she can be so wicked. But her haircut is not funny in the slightest. Nor is being accepted into the Globe troupe. I told her what she was proposing was impossible. She replied that not being in the actors’ company was the impossible part.” The mother blows her nose. “She told me to come talk to you. She said you’ve helped me with many things since you’ve been here, and maybe you can offer some advice. Or even a solution. She is right. You are very wise, Master Julian.”

“Yes, I’m like a little Yoda.”

“Like a what?”

“Never mind.”

“I’m going to wring Beatrice’s neck next time I see her. She has absolutely no common sense—like all old maids.”

Julian nods with fake understanding.

“Tell me what to do,” Aurora says. “Something that doesn’t involve her being on the stage.”

“I don’t know what that might be,” he replies. The stage is her life.

“Well, she can’t go to London, that lepers’ colony! It’s all plague and fire down there. The city spits out black skeletons. Is there anything else she can do? Think! Anything at all?”

Julian suppresses an incredulous whistle. Wow. Mary is good.

“As a matter of fact,” he says, after a judicious throat-clearing, “did you know that the Fortune is auditioning for new members to join the Admiral’s Men to be in a production of Two Gentlemen of Verona? There is a role in it that’s perfect for Lady Mary. Philip Henslow is casting it now, to premiere in June. I know Mary is supposed to be getting married at the end of June—”

“Not supposed to be. Is.”

“Yes, well. I assume Lord Falk cannot know of this?”

“He can never know!”

“Then tell her that’s the condition of your approval. She can join the troupe but must leave the production before her wedding day. And,” Julian adds, “if you like, I can drive her to the Fortune. I can wait for her, watch over her. The flowers are growing nicely, I can do my gardening and chandlery work in the morning, and go to Smythe Field to pick up the things we need while she rehearses. There’s a butcher’s near there and an adequate apothecary. And, I happen to know Sir Philip. I could put in a good word for your daughter. Last week, I rid him of a rather unsightly facial wart by a light application of the usnea lichen shrub boiled in a tincture. He is ever so obliged to me.”

Aurora embraces Julian, her eyes watering. “Oh, Julian! It’s a wonderful plan. You’re simply a Godsend. I’ll go and speak to Lady Mary at once. I hope she’ll approve.”

“Yes,” Julian says with a straight face, “her approval is key.” That Mary!

Aurora rushes inside the house, past a motionless Krea, watching Julian like a fearful owl. Krea doesn’t know what the two of them have been plotting, but she knows they’ve been plotting something. “Poor lady,” Krea says. “In childbirth, all grief begins. Lady’s daughter has learned that lesson well. A shame Lady herself has not.”

“Lady’s daughter has not learned that lesson well, what are you talking about,” Julian says, his smile fading. “And Lady Aurora doesn’t see it your way, Krea.”

“Oh, but Lady will,” Krea says. “She will.”

45

Sebastian

THAT NIGHT JULIAN WAKES FROM A DREAM SO VIVID IT MAKES his loins ache. He dreams Mary’s bare flesh is in his hands, and she is on top of him. Jerking

awake, he opens his eyes, but it’s black outside, and there’s no moon. It’s like being in the cave. There’s a breeze from the flapping window. Did he leave it open?

There’s a weight on top of him. A soft hand touches his face. He exhales.

Shh, Mary whispers. Often Krea sleeps in the kitchen.

Not a dream then? Julian tries to reach up to touch her face, but he can’t move. Her knees are pinning his arms to the bed.

Your beard is growing in, finally. Why was your face shaved when you first came to us? Don’t they know in your Wales that the longer the beard, the more virile the man? She caresses his face from forehead to jaw.

Mary?

Are you expecting someone else? Krea, maybe?

He tries to move his arms. What are you doing?

You don’t know?

Her hands rub his chest under his shirt, play with the quartz stone. Her soft lips graze his mouth, his bearded cheek, his closed eyes. The scratchy covers have been pulled off. Now he’s covered with crinoline and silk chemises. He yanks his hands free and reaches up to touch her—and groans. She is bare from the waist up. Shh, she says, fussing with his nightshirt. Her head lowers to his head. Her lips kiss his lips. How is he supposed to stay quiet? Let me take off my shirt, he whispers, tearing it off. He circles his arms around her back, presses her breasts into his bare chest, loses his breath, emits a sound somewhere between agony and ecstasy. Are you a mirage, he whispers, or are you my lost and true girl?

Shh, Mary whispers back.

You too, he whispers, cupping her full breasts. It’s the first time he has touched a woman since she died.

My love, I found you again.

Thank you for helping me with my mother, she says. You gave me what I want and made it seem like it was all Mother’s idea. She now insists I audition at the Fortune, she’s practically ordering me to! A day ago, she thought death was preferable to me being on the stage and now it’s the only thing I must do. You did that, Julian. I don’t know how. She rubs her breasts, her hardening nipples back and forth against his chest.

Mary, he haltingly whispers.

Don’t say my name.

Mary.

What, you don’t want this?

His silence is her answer.

I don’t hear you, Julian.

Mary. His voice breaks.

They kiss a long time, her arms under his neck, his arms around her. He fumbles with her starched petticoat, with her chemise, he is trying to find her naked hips. Their breath grows short, their two bodies frantic.

What are you doing.

What does it feel like?

Stirring up a cauldron of trouble is what it feels like.

Then that’s what I’m doing.

She is deliverance, soft and warm. Maybe in her riding discourse with him she is all sharp edges, rocking on a hard bench on top of the world in public, but here in the dark, she is hot flesh in his hands. Her contours may be different from the girl he had known, the clavicles and the hair shorter, the hips and thighs rounder, the breasts heavier, but her full lips kiss him the same, if slightly more wildly, and she moans the same, if somewhat more mildly, and now it is he who’s begging her to be quieter. She swings her breasts against his face, smothering him. They dry mill against each other, their bodies in rhythmic motion, but Julian knows how this ends—the milling won’t remain dry for long.

The other day I watched you wash in the river, Mary says. Did you see me hiding?

No. He can barely hear her. I think it’s supposed to work the other way, he says. I’m supposed to watch you washing naked in the river.

I’m a lady, not a vagrant, she says. I take hot baths, I don’t wash naked in cold rivers.

Aha. His eyes closed, he imagines seeing what’s in his hands. I touch, therefore I am. I feel, therefore I am. I love, therefore I am.

You were so slim, so handsome. Your shoulders looked strong, your arms. Everything on you looked so strong.

His breath is shallow, his hands more ardent. Her body squirms on top of him as he grinds against her, her breasts in his hands, her nipples in his mouth. Like most men, Julian is a visual creature, and he likes to see his women, and especially he would like to see this woman, the woman, but tonight, the blackout is a fourth dimension. He sees her fully, flying and audacious. He has forgotten about the cave and the dark omens. He has washed in the River of Wells and has been healed by its waters. In her honor he has grown his hair long, worn rags on his body and red satin jackets, his grief and loneliness have been washed away, and she has pierced through it all, a fireball in his pale night.

It’s not true that love returns strongest only to the broken.

Though maybe it is.

I didn’t think I would ever hold you again, Julian whispers, his voice cracking, barely stopping himself from saying Josephine.

He doesn’t trust himself. If he holds her any closer he might suffocate her. Yet, it’s not close enough. Julian needs to be inside the space where there is no inside and no outside. But it’s not where Mary is yet. How could she be? She is drawn to him only for this moment while he is coupled to her for four hundred years of empty beds. Once again, they are not in balance.

How far are you taking me, Mary? he whispers. Because I don’t have far to go.

I wish I could take you all the way, Julian, where you want to be, and where I want to be, but I can’t, Mary says. We can’t get that far, I’m sorry.

Is it the wrong time of the month? I don’t care about that.

She pulls away from him in the pitch-black night.

Why would you say that? Her body stiffens.

Julian pulls her back to him, skin on skin, breath on breath. I don’t care about anything.

Yes, you’re like all men. But I care about things, Mary says. We can’t do the thing you want because bad things can happen, and I can’t have them happen to me. She breathes out, a wingless damaged thing. I can’t have them happen to me again.

Even in his ardor Julian is knocked down by her words.

He holds her head in his hands. I will be careful. I promise.

That is what all men say.

His shiny desire dampens.

All men have said this to you, Mary?

Furious rustling is his response. The weight of her open corsets and billowing skirts slides off his body. He is light again, and heavier than ever. The latticed casement creaks and swings. Wait, he pleads, but in the black night it’s all gone, the dream, the girl, the noise, the breath, the lust, the comfort.

Only love remains.

***

The next morning, with Aurora’s hearty approval, Julian gets Cedric to harness the carriage instead of the wagon and takes Mary to the Fortune. It’s just over a mile from the house, but Mary refuses to walk because she is not a commoner. This, after riding with produce in the back of his wagon like a peach or a plum. She is curt with him, won’t look at him. They leave early, before Edna can fire off her shrill questions. The only ones up are Cedric, who never says anything, Dunham, who is too busy carrying buckets of filth to care, and silent Krea, who watches them leave.

Julian sits on the driver’s bench without Mary, the reins in his hands. Mary is in the carriage, a cloak over her man’s clothes, a wig on her head. They’ve stopped being equals. He’s now her driver.

“Mary,” Julian says when they’re near Fynnesbyrie Field.

“I don’t want to talk to you.”

“After last night, you don’t want to talk to me?”

“After what you said last night, yes. Quiet. Mind the road. I’m trying to learn my lines.” She pulls the folio in front of her face, as the carriage bounces over the potholes. “Poor forlorn Proteus, poor passionate Proteus,” she recites.

She auditions for the Admiral’s Men as Julia. The long-haired wig serves her well. She pulls the wig off when the time comes to read for the boyish Sebastian. The short hair serves her even better. She gets the part before they leave the theatre. Henslow himse

lf announces her admission into the troupe as he shakes Julian’s hand. The rehearsals will last two weeks. She’ll have almost four weeks with the play before her wedding, just as she’d had with Paradise in the Park. Except this time it’s the wrong wedding.

On the way home when Julian tries to talk to her, she shuts him down. But in the black of night, she comes to him again. “You upset me so much with your words,” Mary says, after climbing through the window and on top of him.

“I’m sorry.” He wraps his arms around her. “What you said upset me.”

“I don’t know why it should. I don’t know why it would. Was I faithless to you? Were you my betrothed?”

“Yes,” Julian whispers. “I am your betrothed. Do you feel how I hold you? Like you are mine. Like I am yours.”

“Why do you want to touch me at all if you think I’m such a soiled creature?”

“I don’t think you’re soiled, Mary.” He pulls her loose flowing gown to her stomach. “I wish I could see you,” he says, her body in his gripping hands. “You feel so beautiful.”

“You’ve seen me during the day,” Mary says. “I am beautiful.”

He kisses her throat, breathes into the space between her breasts as if to animate her. He sits up in his hard bed, pillows propped against the wall, and she straddles him, wriggling in his lap. Julian wants to lay her down, wants to be on top of her. He is breathless and rapacious. What a heady cocktail she is in his monastic bed off the buttery by the kitchen. She has awakened his body. She has his soul. She holds it in her careless hands, the hands that wave mistreatment on Henslow’s stage as her lips ask, how do I prevent the loose encounters of lascivious men?

Do you want me to touch you? Julian whispers.

You are touching me. You’ve been caressing me top to bottom since I’ve come through your window.

Yes. I mean . . . do you want me to touch you to make you fly?

I don’t know. Are you saying what you mean? Or is it like always with you, a play on words?

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

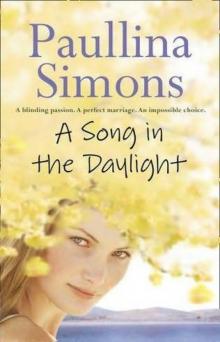

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)