- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 33

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 33

“So if you didn’t let him in, how in the name of Dickens did he get here? And more important, why?”

All eyes turn to Julian, even hers.

Mirabelle is composed, white-necked, white-faced, spotlessly clean and coiffed. She is an elongated statue of the animated fiery girl who fought to survive the alleys of St. Giles. That girl lived. This woman exists. Though she is exquisite, Julian can’t tell if she has ever strolled through a garden of pleasure, or even desired to. She is elegant, yet slightly forlorn. Something blackens the pastel edges of her beauty.

“Answer me, child,” George Airy says. “You know how precious time is, especially mine.”

“Everyone’s time is precious, Uncle George.”

Silently, Julian concurs.

“Then answer my simple query. Who is he?”

Mirabelle’s voice is mellifluous and carries far despite its softness, despite its breathiness. She always sounds like herself. There’s never any mistaking it. The present voice carries farther than most, because of her height. It’s got a wry, dry tinge to it, a slight I-know-things-better-than-you air. “He looks like a seminarian to me, Uncle,” Mirabelle says. “A man of the cloth. Look at his clerical collar.” She points to the headlamp. “He must be looking for our Charles Spurgeon, the Prince of Preachers, isn’t that right, sir?”

Julian fights to stay as composed as she is. She is helping him out, rescuing him. Why?

“He’s looking for Spurgeon in my observatory?” Airy casts Julian a skeptical unwelcome gaze. But the astronomer must detect something unscientific in the invisible dynamic between the stranger and his niece—sense some new energy that has charged the stale particles in the room—because his high-handed demeanor softens. He wrinkles his prominent brow. “You’re far afield of the New Park Chapel,” Airy says, finally addressing Julian. “We’re in Greenwich, sir, and the chapel is in Southwark. You’re in the wrong part of town.”

“He is lost,” says Mirabelle.

“I’m not lost,” Julian says. His voice is hoarse. “I’m found.” Those are the first words in his new life.

“Where did you come from, good sir?”

“Bangor.” Julian chose Bangor because it was, then as now, one of the smallest towns in Britain. “It’s a cathedral city in Wales, near the Menai Strait…”

“I know where Bangor is,” George Airy says. “It’s 4 degrees of longitude west of here, 4.1 degrees to be precise.”

“Yes, sir.”

Woe to him who thinks he can outsmart a scientist.

“What is that you’re wearing?” Airy asks. “Is that some type of Welsh attire? We’ve never seen it in London.”

“We certainly haven’t,” Filippa says, her chest heaving out of her flouncy ruching.

“We wear this in the mines and seas of Wales,” Julian says. “It’s a wetsuit made to protect me from the elements when I travel.” He snaps the Thermoprene to show them. “It’s windproof and water-resistant.”

Filippa looks impressed.

A prickly, angular woman in her forties pushes through between the girls. She’s panting and fretful. She’s got a severe hairdo and her lace collar is so tight it appears to be choking her throat. “I beg your pardon, Mr. Airy, sir, for all the commotion,” she says, her voice a steel string. What have my girls done now? I take my eyes off them for a second and—Mirabelle, Filippa, explain yourselves!”

“Where have you been, Mummy?” Filippa asks. “Talking to Mr. Sweeney again?”

Filippa’s mother raises her hackles like a porcupine. “Do not be cheeky, my darling. Mr. Sweeney and I may have discussed the weather for a few minutes, a few seconds…”

George Airy gives Sweeney a condemning glance. Sweeney doesn’t know where to look.

Amid the recriminations, Mirabelle glides forward. The spot where Julian stood a blink ago with a grim and fearful Ashton is now inhabited by his light and fearless Eurydice. Ashton had gripped his forearm. “Don’t do this again,” Ashton said. “I beg you. Nothing good’s going to come of it.”

Unlike Ashton, Mirabelle says nothing. Nor does she touch him.

Julian turns to the Astronomer Royal. “You’re George Airy, aren’t you? You’re famous at Bangor College, you know. The head of our Literature Department has heard that you’ve developed special lenses for astigmatism. They’re revolutionary. The department chairman asked me to speak to you while I’m in London to evaluate this new technology. We have several professors, myself included, in dire need of better optometric equipment.”

“Mummy, he’s a professor!” Filippa squeals.

George Airy nearly squeals himself. “You’re a professor?” And close on its heels: “They heard about my lenses all the way in Bangor?” The peacock tries not to open his tail. “Well, I’m delighted, though I’m not sure how this can be. I did give a pair to my sister, Mirabelle’s mother. She taught piano at the London Conservatory. Aubrey Taylor. Perhaps you’ve heard of her?”

“I’m afraid not,” Julian says. “But don’t the lenses have the same curved aperture technology you used to build this Transit Circle? With the aperture width of eight inches and a focal length of over eleven feet, I believe your telescope is the most accurate in the world, isn’t it?”

George Airy sputters. “How did you—how did—how—”

“I must have read about your lenses in an academic paper.”

After that, Julian can say no wrong and do no wrong.

The astronomer cannot look more flattered, more gratified. “Well, I am pleased indeed. I only developed the lenses to correct my own poor vision,” Airy says, “and yet look how beneficial the technology has been to my country. You’re a professor, you say? Of mathematics, I hope?” The astronomer smiles. “I used to be a professor of mathematics. And then a professor of astronomy. I quite enjoyed my time at Cambridge.” Airy attempts to become businesslike again, tap-tapping his parchment as if formulating a plan. “Mirabelle, dear girl, I have a wonderful idea. Why don’t you accompany this fine young man to Charles Spurgeon and make a proper introduction. We can’t just send him on his way. That would be terribly inhospitable. And Charles is so fond of you.”

“I have so much to do, Uncle…”

“So what’s one more thing? Introduce Charles to…what is your name, dear sir?”

“Julian Cruz.”

“Julian Cruz,” George Airy repeats. “That’s Welsh?”

“Yes,” Julian replies without inflection. “Iolyn Corse is the proper way to say it.”

“Julian Cruz!” says Filippa.

Julian waits, his quiet gaze on the face of the only girl in the world, as ever searching for a blink of retention, recognition, memory. With his whole being, he is yearning to see a trace of himself. Mirabelle doesn’t acknowledge him, but neither does she look away. Only her mouth moves, imperceptibly, inaudibly repeating his name so no one will hear.

Filippa’s mother gives her daughter a shove, and the small girl lurches forward. “I’m Filippa Pye.” The girl extends her hand to Julian. “Pleased to make your acquaintance. This is my mother, Prunella Pye.”

“Pleasure is all mine,” Prunella Pye pants, hooking Julian’s hand with her clammy, bony fingers.

George Airy drags his niece forward, in front of Filippa. “And this is my niece, Mirabelle Taylor.”

Julian tilts his head. “Pleasure to meet you, Miss Taylor,” he says. She doesn’t extend her hand, and he will not presume to impose his paw on her. Besides, his paw is shaking.

Lightly Mirabelle smiles. “Julian Cruz,” she echoes. “So, then, you’re not Charles Spurgeon’s father? Our esteemed pastor has been waiting for his father to visit from Colchester. But we fear the man is ill and may not be coming.”

The priest’s father! Julian must look worse than he thinks. “Father?” He can’t help it. Pride gets the better of him. “How old do I look?”

“Oh, not especially old, I suppose.” Mirabelle’s dark eyes flicker ever so slightly. “Our darlin

g reverend has just turned twenty.”

Julian’s eyes flicker back.

Filippa swings around Mirabelle, planting herself in front of her. It’s the Conga line. “We’ll all take you to Mr. Spurgeon, sir,” she chirps.

“Oh, no need to bother yourself, Pippa,” George Airy says. “You and your mother do too much already. Don’t you have a ball to prepare for? That ball isn’t going to throw itself, you know.”

“It’s no bother at all, Mr. Airy,” Filippa says. “In fact, there’s really no need for Miri to come with us.” (Julian flinches when he hears the princess called by her rookery name.) “We all know how busy Mirabelle is these days. Why, she still hasn’t finished sorting your documents.”

“Oh, that trifle,” Airy says in the tone of a man who cares not a whit for organization, not one whit.

“But, sir,” cries Filippa, “you said she must work harder to transcribe your notes and separate your correspondence! And she got your ledger entries wrong this morning.” Filippa looks up at Julian. “Mr. Airy invented a new system of accounting called double-entry, Mr. Cruz. But math is confusing for Mirabelle, entering the same information twice into the debit and credit columns. She makes many errors.”

“Really, Filippa, you worry yourself over nothing,” George Airy says. “I will check over the numbers myself. Double-entry accounting is one of my greatest joys.” Airy’s rounded nose reddens. “Mirabelle, it’s settled then? You will take this man to Charles Spurgeon and not disappoint me?”

“As you wish, Uncle,” Mirabelle says. “I don’t like to disappoint anyone.”

Filippa persists. “But what about labeling your boxes, Mr. Airy?”

“Mr. Sweeney will label them.” Airy takes a shallow bow, kisses his niece on the cheek and rushes off with his cane and his papers.

“What boxes?” stammers Sweeney.

“Oh, it’s not hard, Mr. Sweeney,” Mirabelle says dryly. “Remember last month when you helped me label Uncle George’s empty boxes, ‘empty’? Do that, just more of it.” Mirabelle turns to Julian. “Order is the ruling feature of my uncle’s life.”

Filippa steps between them. “Mirabelle,” the girl says, “but what about your appointment at the Institute at three o’clock? Have you forgotten all about Florence and the Institute?”

“Hush now,” Mirabelle says. “It’s barely noon. Plenty of time for everything.”

Stepping away from the women, Julian switches off the headlamp and removes it from his neck. He’s got to sort himself out. He’s mired in a bog. He needs his money. And if it’s no longer there, he needs to find a prizefighting ring and earn some money. If he’s ever going to present himself to her, and that’s not a given, he needs to present himself to her as a strong smart man, not a crestfallen pauper in a wetsuit.

His arrogance and desperation in St. Giles didn’t serve Miri’s salvation or his own. He’s been given another chance by the angels or demons. Will he take it? Can he do it this time before he runs out of time? Devi didn’t think so. But Julian has made it his life’s business to refuse to accept implacable facts.

He tips his proverbial hat. “Perhaps I can meet with Mr. Spurgeon another day, ladies.”

“No, you can’t leave!” Filippa cries.

Julian can’t explain to Filippa and her mother that he is not fit to walk alongside that woman. Mirabelle must notice his self-conscious embarrassed hesitation. “I see that in your travels, you have misplaced your coat, Mr. Cruz.” She turns to the caretaker. “Mr. Sweeney, would you please be so kind as to lend Mr. Cruz your cloak? Yes, Mr. Sweeney, the cloak you’re wearing, that one. Right off your shoulders.”

A grumbling Sweeney hands it over.

Julian can’t help but smile. “Some things never change, do they, Sweeney?” he says, throwing the black cape over his shoulders, covering his ridiculous wetsuit, and feeling better. “You’re still giving me your coat.”

“Whatever do you mean,” Sweeney says. “I never give you my coat in my life.” The portly gentleman looks discomfited. “Keep the coat. Consider it almsgiving.”

“Oh, that is so kind of you, Mr. Sweeney!” Prunella says with undue exuberance.

Filippa pulls on her mother’s arm. “I hope Mrs. Sweeney will be as delighted as you to hear that her husband has given his coat away,” she says.

Prunella yanks out her arm and fluffs up her sleeve. “Mind your own business, my impertinent darling,” the bony woman says, heading for the door. “You forget yourself. Unlike you, your widowed mother does not need a chaperone.”

Filippa hurries after her. They all walk out into the courtyard on top of the hill. The August air is muggy and still. Before they turn their backs to it, Julian catches a long glimpse of the Thames in the distance below them, meandering through hazy London as far as the eye can see.

Mirabelle leads the way to the carriage, waiting for them behind Flamsteed House. Prunella and Filippa trail behind. Since he and Mirabelle are walking without speaking, with astonishing clarity Julian can hear Prunella’s shrill voice scolding Filippa. “It’s just good manners, Pippa. This man is a professor, highly educated. He’s from Wales. He may be a nonconformist. They are serious thinkers over there, the Welsh nonconformists. Practical, temperate, hard-working. In many ways, they mirror the Puritans. They are utterly unimpressed by flamboyant displays from their women, by physical contact, really, of any kind.” Julian keeps his eyes in front of him, lest he accidentally catch Mirabelle’s inquisitive gaze, wanting to know if what Prunella is saying is in any way true, and God forbid she sees in Julian’s eyes how untrue it is.

“This man needs a serious, unsensual demeanor from his young lady,” Prunella continues. “So adjust your behavior, dear heart.” Now Prunella lowers her voice, but on the empty road between the trees, the only thing that’s heard is her irritable alto. “Before it’s too late for you, like it’s too late for our Mirabelle.”

“Are you sure it’s too late for her, Mummy?” Filippa says, the anxiety sharp in her voice.

Julian and Mirabelle both pretend they’re deaf. Her face expressionless, Mirabelle ties the ribbon ends of her white bonnet under her chin.

Julian clears his throat. “I heard your uncle mention there was a sun flare today, Miss Taylor,” he says. “Do they occur frequently?” First order of business between them: mystical phenomena.

“Not too frequently,” Mirabelle replies. “We keep a record of all anomalous events at the Observatory. If you wish, you can ask my uncle to let you take a look at the data.”

“Going back how far?” What is Julian hoping for? That somehow George Airy kept records on sun flares going back two hundred years? Come on, Julian, shape up.

“Since 1834. The year he became Astronomer Royal.”

Julian nods, trying to verbalize the second order of business between them. “Your uncle mentioned that your mother teaches piano. Do you play?”

“My mother is a good teacher,” Mirabelle replies, “but I’m a poor student, I’m afraid. I play, but I don’t have the flair for it.”

“Do you prefer the spoken word?”

“Why, yes. Yes, I do, Mr. Cruz. How did you know?”

“Lucky guess.”

“I used to have quite a flair for the dramatic,” Mirabelle says wistfully. “But not anymore. Nowadays I occasionally read poetry.”

Do you stand on a crate over Rockaway Bay, Mirabelle? Julian wants to ask. “What kind of poetry?” he asks. “Shakespeare’s Venus and Adonis perhaps?”

“Why, yes, Mr. Cruz!”

The look on her face is less calm, slightly incredulous.

Julian smiles.

Overhearing, Filippa catches up to them. “Mirabelle used to sing and dance like a carnival performer. She liked the applause, didn’t you, Miri?”

“A little too much, if you ask me,” Prunella intones from behind.

“I did not,” says Mirabelle. “Not too much. Just enough.”

“And if there was no chance for appla

use,” Filippa says, “then you could just throw money at her.”

“Filippa is joking.”

“I would find that highly entertaining, Miss Taylor,” says Julian. “Seeing you sing and dance, I mean.”

“Which would you do, Mr. Cruz,” Filippa asks with a glint, “applaud or throw money?”

“I would do both.”

Mirabelle stares at her shoes, suppressing her own glint.

During the twenty-minute ride to New Park Chapel, Filippa info dumps on Julian. She has been endowed with a biblical propensity for small talk. There is something desperate in her ceaseless verbal patter, as she sits by Julian’s elbow, her smile pasted on, her mouth in motion.

Across from them, an unruffled Mirabelle sits next to Prunella, both women watching Filippa besiege Julian, one with detached amusement, one with public dismay.

Filippa tells him where they live (in Sydenham, Kent), how long she and Mirabelle have been friends (since childhood), and how many jobs and separate responsibilities Mirabelle has at the moment (eight).

“What do you do, Filippa?” Julian asks, to be polite.

The girl takes the question as a strong sign of his interest in her. She unfurls. “Oh, don’t worry, as little as possible, Mr. Cruz! I make pudding, I darn stockings, and I embroider bags. Mummy and I are also organizing a ball.” In the next breath, Filippa invites Julian to the ball, “as my honored guest of course.”

The dance is at the end of August. Julian protests. He says he doesn’t know if he’ll be in London then, but Filippa refuses to take no for an answer.

Julian steals a glance at Mirabelle.

“Mirabelle probably won’t attend,” Filippa says, catching him looking. “She said she was busy. She’s—”

Mirabelle interrupts. “I don’t remember saying I was busy, Pippa.”

“You did. Doctor Snow asked if you would honor him by attending and you said you were too busy.”

Mirabelle allows herself a small roll of the eye.

“Who is Doctor Snow?” asks Julian. Does she have a suitor? Well, why wouldn’t she? Look at her.

“The esteemed John Snow, the famous scientist. Have you heard of him?”

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

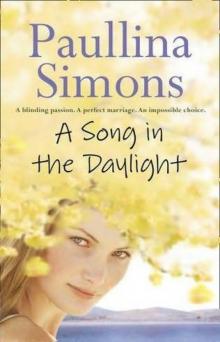

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)