- Home

- Paullina Simons

The Tiger Catcher Page 32

The Tiger Catcher Read online

Page 32

“Well, yes,” Mary says breezily, “she did advise me to keep my devil’s portgate shut before a terror befell me.”

“Um—devil’s portgate?”

“I do not wish to discuss it further. And perhaps you should be less distracted by me, you don’t seem to know where you’re going.”

“I know where I’m going.” And I know I’m going with you. “I’m not distracted by you, my lady. That is, unless you wish me to be. I’m trying to find another way inside the city to avoid this blasphemy of a road. But don’t worry, soon we’ll be at Cripplegate. Maybe we can stop somewhere and have lunch?”

“Have what?”

“Dinner, I mean.” Julian is never going to get used to lunch being called dinner.

“We have no time for dinner,” Mary says. “We have to be on the other side of the river before 12:30.”

“We have plenty of time.” Julian glances thoughtfully at the sky, as if he can read the ancient scrolls on it. They left the house at sunrise, how late could it possibly be?

“You’re about to turn into Turnbull Street,” Mary says. “Do you call that avoiding filth? That’s the brothel quarter, where the bawdy houses are.”

“Thank you,” he says. “I know what a brothel quarter is.”

“Oh, I’m sure you do.”

“Lady Edna enlightened me.”

“Yes, she does like to discuss the topic of brothels at some length.”

“And in great detail.”

Mary almost giggles. “Not enough detail, obviously,” she says, trying to keep a straight face, “for, a minute ago, you didn’t know what a devil’s portgate was.”

“I knew what it was,” Julian says. “I was being polite, as you had requested. Continue with your fascinating story. What did you say after your mother told you to keep the, um, gate closed?”

“I told her—too late, Lady Mother.”

“You should stop joking with her. You know how literally she takes you.”

The girl says nothing at first. “That’s when Mother decided to marry me off to save me. But not to Massimo, of course.” Mary sighs. “There are so many things Mother doesn’t understand.”

“I think your mother’s trouble is that she understands them too well,” Julian says.

“She doesn’t know where my heart lies. It’s not with Lord Falk.”

“Is it with the Italian?”

Mary shrugs. “He was entertaining. Like a play. A diversion. But I don’t want to be some silly lady dying a slow death in a fusty house.” She presses her hands to her chest and lifts her face to the sky. “I want to be on the stage, in the open air, in an amphitheatre! I want to hear the people in the galleries applaud and the groundlings laugh and cry and cheer!”

“But they still won’t be cheering for you, Lady Mary,” Julian says. “They’ll be applauding for the thing you’re putting on for them, for someone else. Don’t you want to be loved for the young woman you actually are?”

“Don’t speak to me so presumptuously about love,” she says. “And no, I want to be loved for the woman I pretend to be.”

Indeed, Josephine, indeed. “Which is what? A girl playing a boy playing a girl?”

“Precisely!”

Julian pulls up on the reins, slows down the horse and turns to look at Mary’s pearl-skinned face, her full, red, decidedly un-man-like lips, her white neck peeking through the loose black twill of a man’s cape. “You’ll never look like a boy,” he says, his voice lowering. “You won’t fool any man.”

“More fool you that you think this,” Mary says, throwing off her hood under which she proudly displays her dark crew-cut hair. He gasps. She is delighted by his shock. “Yes, Master Julian, the lady is the pretend part. Every day, I wear a wig to fool the world. I fool you, Lady Mother, Edna, everyone. This is the real me. A girl with boy hair.” She smiles with gritty satisfaction. “Stop gaping and drive. Time’s a-ticking.”

“Does your mother know you have no hair?”

“Make an effort not to be constantly foolish,” Mary says. “Of course she doesn’t. Only Catrain knows because she helps me bathe.”

Julian drives on, his mind whirling. “Katherina is a big commitment, Lady Mary. How will you explain your day-long absence to your mother? To be at the Globe by call time, you’d have to be away from home six days a week. Are you going to head back across the bridge at night, by yourself? Or have a boatman ferry you across? It’s not safe for a lady, even one who’s dressed as a boy.” Julian is just dreaming out loud. He will be the one to take her to the theatre, he will be the one to never leave her side.

“I don’t feel like explaining myself to you, Welsh rabbit, foreign scullion,” Mary says. “Since you clearly can’t do two things at the same time, stop speaking and drive.”

Julian drives and Mary goes on speaking. As they pass the gatekeeper at Cripplegate and enter the northern part of the city of London, she tells him if she becomes an associate member of the troupe, she will run away from home.

“That’s your solution,” Julian says, “to run away to the Globe? Your family will find you instantly. Take you home by force if necessary. They’ll alert the Master of Revels that one of his Lord’s Men is not a man, and Richard Burbage will sack you.”

“They’ve heard of our Richard Burbage in Wales?” Mary says. “I didn’t think the Welsh knew how to read.”

Richard Burbage, Julian wants to tell her, is one of the greatest and most beloved actors in the history of English theatre. The mourning after he died was so intense, it overshadowed the death of an actual queen. He is buried in Shoreditch, at St. Leonard’s, near Devi. Julian has read Burbage’s short bio on a plaque while walking by. The words on his long-lost tombstone had been: “EXIT BURBAGE.”

“Do you know what running away is?” Julian says. “Running away is leaving early in the morning before anyone wakes up and traveling to a place where you can’t be found. It’s changing your name. It’s finding a different stage.” He turns his head to her. “It’s finding a different life.”

Mary stares into his face. Julian doesn’t care about the turmoil she must see in his eyes. He lets her see it.

“Change my name to what?” Mary says, frowning, slightly trembling, dreaming of the possibility.

“Anything you want.” Julian wants to press the red beret to his chest. “How about Josephine?”

“Josephine Collins?”

“Why not?”

They sit suspended in time.

Julian snaps the reins, and they continue down Vine Yard to Cheapside. The roads are slightly better inside the city walls, because many are cobbled, but they’re also narrower. In front of them on a hill stands an enormous red cathedral without a spire. “What church is that?” Julian asks Mary. Has he lost himself geographically? Vine Yard is where Aldersgate Street is. He is usually so well oriented. He thought they were in the center of the walled city, but he doesn’t recognize the rectangular colossal church.

Mary is back to being peevish. “You don’t know what church that is? It’s St. Paul’s.”

That dark rambling building that stretches for blocks is St. Paul’s? Julian stops the horse. They’re on Ludgate Hill? It can’t be. “Where’s the dome? Where’s the steeple?”

“What dome?” Mary says. “The spire was destroyed by lightning forty years ago. The Protestants and the Catholics both saw it as proof that God was displeased with their wicked ways, so the Queen ordered that the church remain unrepaired until we got ourselves in spiritual order.”

“How’s that going?”

“Slowly.”

The church is a town in itself.

“Is there a gallery inside?” Julian asks, marveling at the massive red cathedral. “There used to be a gallery in the nave called Paul’s Walk.”

“It’s still there,” she says. “It’s for gossiping beggars. Would that be you?”

“And there’s a roof walk. Let’s tie up the horse and climb up, look at the city. The v

iew must be astonishing.”

“Are you dim in the head? Am I a human or a pigeon?”

But Julian is excited. “Come on, let’s go. We can stretch our legs, walk down to Paternoster Row. You love books, don’t you? Back in the old days, Paternoster was home to the largest collection of booksellers and publishers in the world.”

“What old days?”

Julian can’t remember the heyday of the printers on Paternoster Row, Thomas Nelson, T. Hamilton. All the days, past and future have become one unbroken forest. This is what happens when a lost girl’s eternal splendor is your balm and your wound.

Mary refuses to walk with him, but graciously allows a short break for food. They tie up the horse in a corner by Ludgate, pull out some pandemain and ale from her wicker basket, get some carrots and a bucket of water for the horse, and perch at the back of the covered wagon. He’s tailgating with Mary, Julian thinks with amusement, chewing the bread hungrily. Pandemain, the bread for the wealthy, is baked into a size of roll that fits into a lady’s hand. It’s made from well-sieved wheat. Krea bakes the panis Domini but doesn’t eat it herself. The servants get their own, much rougher “household loaf,” stale remnants of pandemain mixed with un-sieved wheat and acorns and peas.

If Julian and Mary wanted to talk, they wouldn’t be able to hear each other without shouting. London is abominably loud. And the stench from the streets is strong. Julian is not used to the stink or the spectacle. The streets inside the walled city are mazes, narrowed by tall Tudor houses, whose second-floor jetties overhang the cobblestones as if entire buildings are about to topple. Crowds of filthy busy people jostle their carts and pull their donkeys, carrying yokes and barrows down the winding lanes over broken stones. Men stroll with pipes in their mouths. “The holy herb,” Mary calls it. “It was brought over from the New World. Have they heard of the Americas in Wales?”

“Yes,” says Julian.

“Well, apparently tobacco from the Americas is good for your health, or so Aunt Edna says.”

Julian refrains from comment.

After lunch, it takes Mary and him a long while to make their way down to the river, even though it’s only a half-mile. There’s too much foot and beast traffic. Children keep chasing pigeons in front of their horse. At the corner of Thames and Farringdon, a brawl has broken out involving a dozen merchants and one fishmonger. It stops traffic in all directions for at least a half-hour.

The Thames doesn’t look familiar. Julian hardly recognizes it. Fast-flowing and opaque, the river is twice as wide as the Thames he knows. To get across to where the Globe is, they can drive the wagon over London Bridge or tie up the horse right here at Blackfriars and hire a boatman. Julian must admit, he’s a little bit curious to see the bridge in its current incarnation. People live on it. Tall, smashed-together houses line the bridge’s parapets. Would his wagon fit between the homes? He’d rather not risk it. It’s over a mile away, and time is short. Still, it would be amazing to see.

They leave Bruno near the embankment and carefully make their way down the muddy slope to the leaden shore. The River Fleet is broad and fast as it empties into the Thames at Blackfriars. The crossing doesn’t look easy. The river banks are swollen. Is the Thames a tidal river? Everything worries Julian, every decision is so precarious. He’s afraid of making the wrong choice.

The little boatman readily agrees to take them across, though he charges them extra, saying that the current is strong with the river at high tide (!), and it will take over an hour. He even jokes with them, saying it’s a good thing they didn’t try to cross the day before, because London was a lunatic asylum. “The new King rode in from Scotland with his entire contingent and entered the city at Temple Bar,” the boatman tells them. “It was absolutely terrible, the mess, the noise, the crowds.”

But as soon as Julian offers Mary his hand to help her into the dinghy, the boatman swears and hurls the half-shilling Julian had given him into the mud. He shouts at Julian not to set foot into his boat, to take his dirty money and leave. Perplexed, Julian backs away and stares anxiously at Mary. Something is happening, though Julian is damned if he knows what it is. But it’s dangerous for her. He feels it. “Let’s go,” he says, trying to pull her behind him.

“No!” She wriggles free. “We paid for a ride, we’re getting a ride.”

“There’s yer money!” The boatman points. “In the filth where yer buggering lot belong, you sodomizing pederasts! What you’re doing is punishable by death. I don’t take your sort ‘cross the river. Death is too good for the likes of ya. Get away from me and me boat before I knife ya. You’re swine herd, you’ll burn in hell. You need an arrow in yer nuts, not a boat ride!”

“What are you on about, old man?” Mary says, with genuine incomprehension.

Raising his oar, the boatman lunges at Mary and swings. Julian steps between them—as if offering the faux boy his arm wasn’t an egregious enough breach of public etiquette. Now he, a grown man, has just made it worse by defending the young boy’s honor. He moves his head out of the way, and the flat of the oar cuffs him on the shoulder. Needles spring to his eyes. But before the boatman can swing again, Julian grabs the oar by the paddle and yanks it out of the man’s hands. “All right, now,” Julian says in a calming tone, as if the man is a wild dog. “Settle down. No sense in flying off the handle—”

The man is incensed. He grabs the other oar and swings it. Julian blocks it with the oar he’s got. They fence for a few grunting thrusts, a few misplaced parries. “Put it down,” Julian says, panting and trying to knock the oar out of the man’s hands. “It’s fine—we’ll go somewhere else.”

“No, we need a ride!” Mary cries behind him. “You got it all wrong! I’m not a man. See? I’m a noble lady!”

She throws off her hood, showing him her monk-cut hair and her makeup-free, milky and hairless face. For a moment, the irate boatman stops trying to bash Julian’s brains in and gapes at her in utter confusion. Julian shakes his head. How does she manage to make a bad thing worse? There’s nothing Mary can do to prove she’s not a man, short of being imprisoned for indecency. It’s hopeless.

Empowered by his righteous anger, the wherryman swings again. Julian blocks and jabs him in the solar plexus with the oar handle. The man loses his footing, staggers, and tumbles backwards into the brown slime. Julian stands over him, the handle at the man’s throat.

“Are you going to stop this nonsense,” Julian says, “or am I going to have to beat you senseless?”

“Beat him senseless, beat him senseless!” cries Mary.

“You heard the lady,” says Julian.

“Don’t hurt me!” the man squeals.

“Oh, you’re not so brave now when you don’t have a filthy oar in your hand,” Mary says, pitching the oar the boatman has dropped into the river. Julian throws his after hers. They float in the shallow water, as the man, cursing and yelling, chases after his paddles, without which his boat is useless.

“Quick, let’s go,” Julian says, not daring to take Mary by the elbow to help her up the slope, lest they be hanged, two men touching in public.

She refuses to budge. “No. We’re getting our ride.” She’s as stubborn as the wherryman.

“Not from him.”

“Well, there’s no one else here. Do you have a boat?”

“Mary,” Julian says, stepping close to her to impart the gravity of their predicament. “Did you hear what he said? He thinks you’re a man. You must now face the consequences of dressing like a man. You didn’t think this part through, did you? The man in the water is about to yell for help, and soon there’ll be a dozen oars pounding us on the head. And then the constable will arrive. Are you ready to explain yourself to the police?”

“It’s your fault!” she cries, shoving him in the chest. “Why did you have to touch me?”

“I didn’t touch you, I offered you my hand.”

“You don’t go around offering men your hand!”

“Well, you�

��re not a man, so there’s that,” Julian says. “But in a minute, we’ll both be at Newgate. So, how about if we resume this argument while we’re driving away?”

“I’m not driving anywhere,” Mary says through her teeth, “unless it’s to the Globe.”

“Not today.”

“Yes, today!” It’s a despondent, high-pitched wail.

“You don’t sound like a boy right now,” Julian says. “You sound like a petulant child that needs to be spanked and sent to bed.”

Mary slaps him across the face and squelches uphill, mud covering her hose to her knees. She swears under her breath. “Do not ever speak to me again,” she says. “Near the horse or anywhere. I hate you. As soon as we get back, I’m telling Mother everything. I’ll get into a little trouble, but you’ll be at the gallows. You’re a despicable man.”

Julian hurries behind her, relieved she wasn’t bludgeoned by an oar and also relieved Mary won’t have to provide evidence to the London police of her irrefutable sexual assets.

At the carriage they continue to spar, but they can barely hear each other. A large loud family walks their giant pet pig past them on Thames Street. Grocers, bakers, fruit sellers, fishmongers shout at the top of their soot-filled lungs, drivers yell at their horses, dogs bark, and Bruno makes his throaty horsey chuffing noises as if he’s about to kick the shit out of both of them with his hind legs.

Julian’s had enough. “Stop it,” he says, loudly enough for her to hear, yanking her away from the rear of the horse so she doesn’t get kicked in the teeth.

She rips her arm away. “Don’t you dare put your hand on me!”

“I don’t want to argue with you anymore,” he says. “You want to go to the Globe? Fine, I’ll take you.” He thrusts his finger up at the bells of St. Paul’s, ringing in the hour. Panting, they count. There are eleven interminably slow gongs. “It’s eleven. Do we have time to get to London Bridge from here, get across, and ride another mile to the Globe? If you think we do, then let’s go.”

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

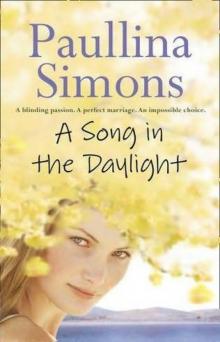

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)