- Home

- Paullina Simons

Inexpressible Island Page 28

Inexpressible Island Read online

Page 28

And there they were.

To the right, in a spacious cave, the river flowed straight and swift. He saw it clearly. There was current and welcome movement. He thought he almost saw, almost! the crystal sliver reflect off something in the distance. Was light filtering in through a crack somewhere? Squeezing his hand shut, he stared intensely into the darkness. Look how fast the river was moving. He had no oars, but he could paddle with his hands to catch the current. He could be at the breach in a few minutes. He would climb out. He would find her. This would all be over. Maybe Cherry Lane, maybe Book Soup, maybe the crest of the Santa Monica Mountains. He still remembered her so well. Mia, Mia.

To the left flowed the same winding, barely rippling, unhurried river he had been on for an eternity, disappearing around the bend between the steep ragged cliffs.

Julian didn’t want to be on the river another second. It had already been too long without her. It was time to see her face. Julian reached into the water with his strong left hand and started paddling, turning the boat into the current.

Oh, no—her crystal! Gasping, he jerked his hand out of the water and stared desperately into his empty palm. He had forgotten that he had clenched his fingers around the shards, and when he opened his hand to paddle, they had fallen out. They were gone, all gone. How could he have been so careless. He just forgot.

Nothing to do about it now. He had to get into the current. He didn’t need the crystal anymore. He knew what she looked like in Los Angeles. Cherry Lane, Normandie, Book Soup. He’d find her.

At first he paddled frantically, and then slower and slower.

Soon he stopped altogether.

His mind kept catching on something it didn’t want to catch on.

The river was at a junction.

That meant there was a choice to make.

Both ways might lead him to her.

But what if only one did?

The short, straight way was better. Because he still remembered! He wanted so desperately not to forget. He thought he wanted that most of all. But what did Devi tell him, what were the terrible words Devi had spoken that Julian barely heard then and wished to God he wasn’t remembering now?

In seven short weeks, in forty-nine days, seven times seven, she will be gone from you again. You know how this story ends, Julian. It’s a loop with a noose.

In seven short weeks she will be gone from you again.

Can you bear it?

Which way the river? Which way her life?

He had tried it already every which way. Every approach, every angle. He tried to warn her, to stay away, to be slow, to be fast, he tried friendship and romance, reserve and abandon, to look far ahead, and to live day by day.

And now another unfathomable choice was rising up in front of him.

When you didn’t know what to do, how did you decide which path to take with the future unknowable and one way infinitely preferable?

Julian knew. The thing you didn’t want to do was nearly always the right choice. You did the thing you didn’t want to do. Did you tell the truth, did you give your love, were you free, did you leave, did you dream, did you work? Did you go to York when your closest friend begged you to go with him, or did you bow out? Did you run into a burning house? Did you hear a baby cry?

Julian was so bone tired.

What if that was the choice he must make—to remain on the river until the end?

But what if it wasn’t?

So many unanswered questions.

He tried to argue himself out of it. He couldn’t see around the bend. Both streams could converge in the same place, probably did converge in the same place, so what was the difference? It was the stupid thing to do, not the right thing. And no one should do the stupid thing. That was his other life hack: don’t be an idiot. Sometimes you needed to use the shortest route between warehouse and shop. Wasn’t this the ideal time to heed that advice?

Julian slumped in the boat, his head hanging.

He recalled something unwanted about Lethe, the river of oblivion.

Only when the dead have their memories erased can they be truly restored. Only after life was pronounced extinct on the streets, the names of which he was so desperately trying to hold on to, could he live again.

Switching arms and lowering his deformed claw into the water, he began to slowly rake with his index and thumb, angling the boat away from the bold current.

With deep regret, Julian raised his mutilated hand and waved goodbye. He couldn’t see a way out. But maybe, just maybe, if one thing was different . . .

Maybe she would live. Live how she wanted, with hope and bright lights, with her dreams and the stage. Live without him, if that’s what it took. Just live. That’s all Johnny Blaze wanted for his rollerblading Gotham Girl, for his ephemeral Ghost Bride. No tunnels of love. Just to live. I vow to thee, my country, all earthly things above, he whispered. Take my life, Mia. Take my life.

The port side hit the dividing crag, the boat lurched and shifted into the meandering stream, and continued to glide forward without a care.

He stood for as long as he could, but eventually he sat down.

And eventually he lay down. Sometimes it felt as if the dinghy was moving so fast that it wasn’t moving at all but standing still, rocking in the cold river. Julian wanted to raise his head and look around, but he was so tired.

And then he didn’t want to get up anymore. He was all right with that. He lay face up, not moving, his eyes open, trying to find light in the blackened cave, find anything that could signal the end of the line.

And when Julian couldn’t remember much else, he lay in the boat, remembering her.

Mia, Mia, the soul of my soul.

They lived.

They dived under the waves of the Pacific. They had picnics under the trees in Fynnesbyrie Field. Walking arm in arm, they saw elephants in St. James’s Park. They danced drunk on the tables in the cellars of St. Giles. They laughed in Grey Gardens and strolled across Waterloo Bridge. They huddled under elk skins in the polar ice. He lay on top of her body, hiding her from Hitler, hiding her from Hades.

They lived. During their brief bright days, he thought they didn’t have time, didn’t have much, there was always regret for the litany of things they hadn’t done. They never bought a house, never traveled, never got married, never had kids, never grew old.

But they had these things. They lived in brothels and mansions, in shelters, and up near the sky. They rode horses, and trains, and ships. They slept out in the open fields and in soft beds.

They lived through all kinds of weather.

They got fake married, put real rings on their fingers, spoke true vows, they kissed and danced and sang in revelry. They held babies, helped save babies. Once they talked of babies.

They were young, hungry, lustful, joyful. They were angry, bitter, fighting, hurting. Their bodies flexed like they were gymnasts; their bodies broke like they were old. They lived in peace and in terror. They lived like they were going to live forever. They lived when death was raining down upon them, and when the night was young.

Together they walked through fire. Together they walked through ice.

The whole world and all that was in it was their Inexpressible Island.

They lived. They lived.

Josephine, Mary, Mallory, Miri, MIRABELLE, Shae, Maria!

You have my faithful heart. You will always have it.

I may forget you, but my love for you is carved into the walls of my soul.

Something will always remain.

* * *

The wind had died down. It wasn’t cold anymore. It wasn’t hot. Julian could almost see the outlines of the stalactites above his head, the etchings on the cave walls of twisting human shapes knotted in love and struggle.

Who holds the keys of hell and death?

Where is Ashton, my lost brother, my companion in trial and tribulation? It has been an eternity without him by my side.

Whose voice is

the sound of many waters?

Whose passion is astride this wind?

The sound of gnarling metal sorrow, bending the embittered human will to another’s, who did that?

You have been graced with seven golden candlesticks, the healer told him. Whether you light them, whether you even can, is up to you.

Seven times, seven weeks, seven swords, seven hearts, seven stars.

Who knows my grief, my misfortune, my poverty, who knows I’m blind and a beggar and says it’s all right?

Who knows my alms, my gifts, my offerings, who knows my love, who knows my heart?

Julian was in agony, the lungs trying to expand, hot needles burning his veins, his body melting.

Who searches my soul for my hidden burdens and my sleeve for the sins I wear?

Who will lend me his ear and give me a morning star?

Who will take the iniquities from my hands and from my overflowing cloak? My sins fall out behind me as I walk. I’ve forgotten my friends, my family, my mother, forgotten those who cared for me. I’ve turned away from joy, thus I’ve turned away from life. Lost in my suffering, I was bound in chains, and I crumbled before what I have not seen. Who has set before me an open door anyway, even though I’m not strong but weak, I’m not rich but wretched, not a prince but a pauper?

Who knows that I’m not the one who needs nothing? My need is so great, my will so small, my misery and nakedness so blinding. Who knows this about me without any need for words from me, and is all right with it?

The winged beasts fly past blaring their trumpets. I say to the mountain and the rocks, hide me, hide me, please hide me from my life.

In supplication Julian raised his arms.

He thought he wanted to check if the charred flowers had formed on his skin, to see her name blazing on his forearm, to feel the scars of their days. It was dark, and he couldn’t see.

Nothing hurt anymore, because thank God, there was no more pain.

35

Perennial Live-Forevers

THE NOSE OF THE BOAT SCRAPED THROUGH THE SAND, BUMPED and stopped moving.

Finally!

Julian jumped out into the shallow water. His hiking boots were soaked and filled with grit. He was confined in a small space, and it was hard to move his arms to get to his multi-tool—though to be fair, it was also hard to see how a multi-tool would help him. In his current predicament, what he needed was an earth-mover.

The ceiling was low; it was not so much a cave as a space between boulders, a space large enough for just him. Light filtered through a break somewhere up above, a glimmer between loose and heavy rocks. He climbed to it, but the rocks crumbled under his feet, and he lost his footing and slid, and the rocks slid with him, packing on top of him. He tried again. Why hadn’t he put crampons on his boots to help him climb?

The rocks were heavy. He couldn’t move them. After many attempts to free himself, Julian panicked. It felt as if he’d been under a long time. He took deep breaths to make sure his lungs were still working, and then searched through his pockets again, one by one. In one of the deep pockets of his cargo pants, he finally found his multi-tool. It was better than nothing. With the end of the needle-nosed pliers, he frantically stabbed around the packed-in dirt, chiseling away at some of the crushed stones. He was always chiseling away at something or other, trying to make openings in stones. He was determined to forge through this damn rock. He couldn’t die down here when he was so close to getting out.

Blinding sunlight streaked through the cracks above him. If only he could get the opening big enough to fit his arm through, he would wiggle out. The cook was wrong, that funny little guy. Julian was okay. His body felt okay. His head really hurt, though.

The crack became a crevice, then a hole, and finally, after some increasingly desperate hacking, a bright opening big enough for his arm, his shoulder, his aching head. He shoved one boulder after another out of the way, and crawled out.

For many minutes, he lay on his back in the dirt, his eyes closed, panting, sucking in the hot air, trying to catch his breath. He was out! That was the most important thing. It had been scary for a while. It was silly to admit it now, but there were intervals when he felt he might never climb out.

The sunlight blinded him, literally blanched his pupils, and it took him a while to adjust to the daylight. Even when he could see, he couldn’t focus well, especially out of his left eye. Things were murky and blurry. Well, sure, didn’t he get blinded in that eye?

No, what was he talking about? When would he get blinded? Julian sat up, hugging his knees. He was so happy to be out of the cave. He was never going into a cave again, he pledged with solemn honor.

He didn’t feel strong enough to stand up yet. He looked around. He didn’t know where he was. Nothing looked familiar, and it was very hot. There were no rolling hills, no hawthorn hedges, no buildings, no pubs, no rookeries, no observatories, no antipodean flatlands, no collapsing streets. He was in the highlands this time, in the dust of pampas grass. It wasn’t recognizable. But it wasn’t unrecognizable either.

He stared at his forearms, looking for damage, for the tell-tale signs of injuries, old or new. The arms were smeared with mud and dust. With his right hand he rubbed the dirt off his left arm to see the marks but couldn’t find any. Was it his imagination, or were there supposed to be marks? Wasn’t one of his arms engraved with lines, dots, symbols, a map of where he had been and where he was going? He stared into his hands. He clenched and unclenched his fists. His hands were sore, his right hand especially from digging so long with a multi-tool not made for digging, but otherwise they weren’t too bad. No broken bones, thank God.

The top of his head hurt. When he touched it, it really hurt. His fingers came back bloody. The back of his neck was sticky with blood, the back of his shirt. Ah, so he had a cut on his head. No wonder he wasn’t feeling great. The hot sun that was nice a minute ago after being in darkness for what felt like forever was now making everything worse. Julian was fruitless and weary.

When he thought he could bear the pain, he felt around the top of his scalp again. Under the swelling, he found a groove under his fingers, a compound depression in his head. Oh, no—he had an open head wound! He had to cover it with something quick—before dust and dirt got in. He didn’t want to take off his shirt in the sun, so he searched his pockets for anything else, and that’s when he realized he had dropped his multi-tool. Probably when he was moving rocks with both hands to get himself out. No, no. He must find it. It was a Leatherman tool and expensive; it had been a birthday gift from Ashton, the first thing Ashton ever gave him, or as Ashton put it, “the first thing he’d ever given anybody.” Julian didn’t want to lose it. Look how it helped him just now. On his knees, with his bare hands, he plowed through the excavated sand, searching for it. He glimpsed something faintly red in the dust and rocks. He brushed the dirt away, flung away the pebbles that covered it, pulled it out of the earth, flattened it out.

It was the red beret.

He couldn’t believe he had brought it with him. What luck. He must have stuffed it into his pants’ pocket at the last minute, and it had fallen out. The beret was dusty but otherwise in pretty good shape. The leather was soft. Carefully, Julian fit it over his head.

And there was the multi-tool in the sand close by! Oh, thank God.

It was time to stand up, get going. Wobbling slightly, he got to his feet. He was so hot.

Okay. Now what?

For a long time, Julian wandered through the desert wilderness, the untrammeled rattlesnake weed and poison hemlock, through the low-lying, burned-out coyote bush. He was desperately thirsty. He should’ve drunk from the river when he’d had the chance. He stopped walking.

What river?

He peered into the hazy distance for a few minutes. He must have imagined it when he was trapped under the rocks, a mirage of water for men lost in the desert. He distinctly remembered dipping his feet into a stream, but his socks and boots weren’t wet.

They weren’t even damp.

Julian kept circling what looked like the same pair of cacti, the same eucalyptus, kept doubling back, tripling back, over this hill and the next, toward the sun, away from the sun. Nothing made any difference. In every direction, it was the same sparse foliage, the same low shrubland. He found a spray of pink live-forevers, a wildflower weed. It had succulent stems. In seconds he sucked out all the liquid inside them. It wasn’t nearly enough. He searched for more, but there weren’t any.

He found a rotting sheep carcass. He stuck his multi-tool inside and maggots exploded out. He thought blood would drain from his body through the hole in his head. Revulsed, he vomited up the bile in his gut. His head wound bled anew.

His mind wasn’t focusing on the terrain because it was anxiously trying to remember something. Something about ice or mountains or both or death. Was it ice and death? He was supposed to know something, maybe about a coming avalanche? Tell someone something.

He sucked the salt from his dirty hands, and then looked at his right hand and thought, wait, I have all my fingers?

It must be heat stroke. Under the brutal sun, for a moment Julian thought he wasn’t supposed to have all his fingers.

He was dying of thirst. Literally dying.

Julian tried to hold on to the tenuous thread of landslide memory, he really tried. But life took over.

As he wandered in the heat and dust, he forgot the ice and the mountains; he forgot about someone else’s death, because his own was looming so near.

And soon Julian couldn’t even remember that he was supposed to remember.

He was having another problem, one that needed to be addressed immediately, or soon it would become his only problem, and then he wouldn’t have any. His head was hurting so bad, it was making him blind. The blood had dried but the skull felt so tender and swollen that Julian had a flashing worry that maybe it was more than just a cut, that maybe it was a more serious head injury. Like a fractured skull. He dismissed the thought. He couldn’t afford a more serious injury out here by himself in the open country.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

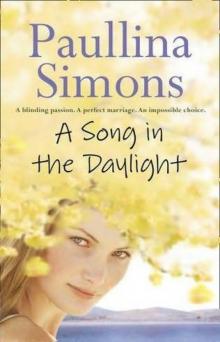

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)