- Home

- Paullina Simons

The Girl in Times Square Page 2

The Girl in Times Square Read online

Page 2

And after he gives them to her, and takes some for himself, she falls contentedly asleep in the crook of his arm, while he lies opened-eyed and in the yellow-blue light coming from the street counts the tin tiles of her tall ceiling. He may look content also—in tonight’s ostensible enjoyment of his food and his woman—to someone who has observed him scientifically and empirically, wholly from without. But now in a perversion of nature, the woman is asleep and the man is staring at the ceiling. So what is in him wholly from within?

He is counting the tin tiles. He has counted them before, and what fascinates him is how every time he counts them this late at night, he comes up with a different number.

After he is sure she is asleep, he disentangles himself, gets up off the bed, and takes his clothes into the living room.

She comes out when his shoes are on. He must have jangled his keys. Usually she does not hear him leave. It’s dark in the room. They stare at each other. He stands. She stands. “I don’t understand why you do this,” she says.

“I just have to go.”

“Are you going home to your wife?”

“Stop.”

“What then?”

He doesn’t reply. “You know I go. I always go. Why give me a hard time?”

“Didn’t we have a nice evening?”

“We always do.”

“So why don’t you stay? It’s Friday. I’ll make you waffles for breakfast.”

“I don’t do waffles for Saturday breakfast.”

Quietly he shuts the door behind him. Loudly she double bolts and chains it, padlocking it if she could.

He is outside on Amsterdam. On the street, the only cars are cabs. The sidewalks are empty, the few barflies straggle in and out. Lights change green, yellow, red. Before he hails a taxi back home, he walks twenty blocks past the open taverns at three in the morning, alone.

PART I

IN THE BEGINNING

You call yourself free? Free from

what? What is that to Zarathustra!

But your eyes should announce to

me brightly: free for what?

FRIEDRICH NIETZSCHE

1

Appearing To Be One Thing When it is in Fact Another

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

And again:

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

Reality: something that has real existence and must be dealt with in real life.

Illusion: something that deceives the senses of mind by appearing to exist when it does not, or appearing to be one thing when it is in fact another.

Miracle: an event that appears to be contrary to the laws of nature.

49, 45, 39, 24, 18, 1.

Lily stared at the six numbers in the metro section of The Sunday Daily News. She blinked. She rubbed her eyes. She scratched her head. Something was not right. Amy wasn’t home, there was no one to ask, and Lily’s eyes frequently played tricks on her. Remember last year in the delivery room when she thought her sister gave birth to a boy, and shouted ‘BOY!’ because they all so wanted a boy, and it turned out to be another girl, the fourth? How could her mind have added on a penis? What was wrong with her?

Leaving her apartment she went down the narrow corridor to knock on old Colleen’s door in 5F. Fortunately Colleen was always home. Unfortunately Colleen, here since she was a young lass during the potato famine, was legally blind, as Lily to her dismay found out, because Colleen read 29 instead of 49, and 89 instead of 39. By the time Colleen finished with the numbers, Lily was even less sure of them. “Don’t worry about it, me dearie,” said Colleen sympathetically. “Everyone thinks they be seeing the winnin’ numbers.”

Lily wanted to say, not her, not she, not I, as ever just a smudge in the reflected sky. I don’t see the winning numbers. I might see penises, but I don’t imagine portholes of the universe that never open up to me.

Lily was born a second-generation American and the youngest of four children to a homemaker mother who always wanted to be an economist, and a Washington Post journalist father who always wanted to be a novelist. He loved sports and was not particularly helpful with the children. Some might have called him insensitive and preoccupied. Not Lily.

Her grandmother was worthy of more than a paragraph in a summary of Lily’s life at this peculiar juncture, but there it was. In Lily’s story, Danzig-born Klavdia Venkewicz ran from Nazioccupied Poland with her baby, Lily’s mother, across destroyed Germany. After years in three displaced persons camps, she managed to get herself and her child on a boat to New York. She had called the baby Olenka, but changed it to a more American-sounding Allison, just as she changed her own name from Klavdia to Claudia and Venkewicz to Vail.

Lily lived all her life in and around the city of New York. She lived in Astoria, and Woodside, and Kew Gardens, and when they really moved up in the world, Forest Hills, all in the borough of Queens. Her dream was to live in Manhattan, and now she was living it, but she had been living it broke.

When George Quinn, who had been the New York City corre-spondent for the Post, was suddenly transferred down to D.C. because of cost-cutting internal restructuring, Lily refused to go and stayed with her grandmother in Brooklyn, commuting to Forest Hills High School to finish out her senior year. That was some wild year she had without parental supervision. Having calmed down slightly, she went to City College of New York up on 138th Street in Harlem partly because she couldn’t afford to go anywhere else, her parents having spent all their college savings on her brother—who went to Cornell. Her mother, fortunately guilt-ridden over going broke on Andrew, paid Lily’s rent.

As far as the meager rations of youthful love, Lily, too quiet for New York City, went almost without until she found Joshua—a waiter who wanted to be an actor. His red hair was not what drew her to him. It was his past sufferings and his future dreams—both things Lily was a tiny bit short on.

Lily liked to sleep late and paint. But she liked to sleep late most of all. She drew unfinished faces and tugboats on paper and doodles on contracts, and lilies all over her walls, and murals of boats and patches of water. She hoped she was never leaving the apartment because she could never duplicate the work. She had been very serious about Joshua until she found out he wasn’t serious about her. She read intensely but sporadically, she liked her Natalie Merchant and Sarah McLachlan loud and in the heart, and she loved sweets: Mounds bars, chocolate-covered jell rings, double-chocolate Oreos, chewy Chips-Ahoy, Entenmann’s chocolate cake with chocolate icing, and pound cake.

One of her sisters, Amanda, was a model mother of four model girls, and a model suburban wife of a model suburban husband. The other sister, Anne, was a model career woman, a financial journalist for KnightRidder, frequently and imperfectly attached, yet always impeccably dressed. Her brother, Andrew, Cornell having paid off, was a U.S. Congressman.

The most interesting things in Lily’s life happened to other people, and that’s just how Lily liked it. She loved sitting around into the early morning hours with Amy, Paul, Rachel, Dennis, hearing their stories of violent, experimental love lives, hitchhiking, South Miami Beach Bacchanalian feasts. She liked other people to be young and reckless. For herself, she liked her lows not to be too low and her highs not to be too high. She soaked up Amy’s dreams, and Joshua’s dreams, and Andrew’s dreams, she went to the movies three days a week—oh the vicarious thrill of them! She meandered joyously through the streets of New York, read the paper in St. Mark’s Square, and lived on in today, sleeping, painting, dancing, dreaming on a future she could not fathom. Lily loved her desultory life, until yesterday and today.

Today, this. Six numbers.

And yesterday Joshua.

Ten good things about breaking up with Joshua:

10. TV is permanently off.

9. Don’t have to share my bagel and coffee with him.

8. Don’t have to pretend to like hockey, sushi, golf, quiche, or actors.

7. Don’t have to listen to him complaining about the short shrift h

e got in life.

6. Don’t have to listen about his neglectful father, his non-existent mother.

5. Don’t have to get my belly button pierced because he liked it.

4. Don’t have to stay up till four pretending we have similar interests.

3. No more wet towels on my bed.

2. Don’t have to blame him for the empty toilet roll.

And the number one good thing about breaking up with Joshua:

1. Don’t have to feel bad about my small breasts.

Ten bad things about breaking up with Joshua:

10. There

9. Are

8. Things

7. About

6. You

5. I

4. Could

3. Never

2. Love.

Oh, and the number one bad thing about breaking up with Joshua…

1. Without him, I can’t pay my rent.

1, 18, 24, 39, 45, 49.

Her hair had been down her back, but last week after he left Lily had sheared it to her neck, as girls frequently did when they broke up with their boyfriends. Snip, snip. It pleased Lily to be so self-actualized. To her it meant she wasn’t wallowing in despair.

Barely even needing to brush the choppy hair now, Lily threw on her jacket and left the apartment. She headed down to the grocery store where she had bought the ticket. After going down four of the five flights, she trudged back upstairs—to put her shoes on. When she finally got to the store on 10th and Avenue B, she opened her mouth, fumbled in her pocket, and realized she’d left the ticket by the shoe closet.

Groaning in frustration, tensing the muscles in her face, Lily grimaced at the store clerk, a humorless Middle Eastern man with a humorless black beard, and went home. She didn’t even look for the ticket. She saw the mishaps as a sign, knew the numbers couldn’t have matched, couldn’t have. Not her lottery ticket! She lay on Amy’s bed and waited for the phone to ring. She stared out the window, trying to make her mind a blank. The bedroom windows faced the inner courtyard of several apartment buildings. There were many greening trees and long narrow yards. Most people never pulled down the shades on the windows that faced inward. The trees, the grass were perceived to be shields from the world. Shields maybe from the world but not from Lily’s eyes. What kind of a pervert stared into other people’s windows anyway?

Lily stared into other people’s windows. She stared into other people’s lives.

One man sat and read the paper in the morning. For two hours he sat. Lily drew him for her art class. She drew another lady, a young woman, who, after her shower, always leaned out of her window and stared at the trees. For her improv class, she drew her favorite—the unmarried couple who in the morning walked around naked and at night had sex with the shades up and the lights on. She watched them from behind her own shades, embarrassed for them and herself. They obviously thought only the demons were watching them, judging from the naughty things they got up to. Lily knew they were unmarried because when he wasn’t home, she read “Today’s Bride” magazine and then fought with him each Saturday night after drinking.

Lily had drawn their cat many times. But today she got out her sketchbook and mindlessly penciled in the number, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49, 49. It couldn’t be, right? It was just a cosmic mistake? Of course! Of course it was, the numbers may have been correct, but they were for a different date: how many times has she heard about that? She sprung up to check.

No, no. Numbers matched. Date matched, too.

She went into Amy’s room. She and Amy were going to go to the movies today, but Amy wasn’t home, and there was no sign of her; she hadn’t come home from wherever she was yesterday.

Lily waited. Amy always gave the appearance of coming right back.

Lily. Her mother forgot to put the third L into her name. Though she herself was an Allison with a double L. Oh, for God’s sake, what was she thinking about? Was Lilianne jealous of her mother’s double L? Where was her mind going with this? Away from six numbers. Away from 49, 45, 39, 24, 18, 1.

She had a shower. She dried her pleasingly boyish hair, she looked through The Daily News and settled on the 2:15 at the Angelica of The Butcher Boy.

While walking past the grocery store she thought of something, and taking a deep breath, stepped inside.

“Excuse me,” Lily said, coughing from acute discomfort. “What’s the lottery up to at the last drawing?” She felt ridiculous even asking. She was red in the pale face.

“For how many numbers?” the clerk said gruffly.

Not looking at him, Lily thought about not replying. She finally said to the Almond Joy bars, “All of them.”

“All six? Let’s see…ah, yes, eighteen million dollars. But it depends who else wins.”

“Of course.” She backed out of the store.

“Usually a few people win.”

“Uh-huh.”

“Did your numbers come in?”

“No, no.”

Lily got out as fast as she could.

18 was one of the numbers. So was 1.

That was in April. After Joshua, Lily swore off men for life, concluding that there wasn’t a single decent one in the entire tri-state area, except for Paul and he was incontrovertibly (as if there were any other way) gay. Rachel kept offering her somewhat unwelcome matchmaking services, Paul and Amy kept offering their welcome support services. They went to see other movies besides The Butcher Boy, and The Phantom Menace and sat until all hours drinking tequila and discussing Joshua’s various demerits to make Lily feel better. And eventually both the tequila and the discussions did.

Lily—making her lottery ticket into wall art for the time being—affixed it with red thumbtacks to her corkboard that had thumbtacked to it all sorts of scraps from her life: photos of her together with her brother, some of her two sisters, photos of her grandma, photos of her six nieces, photos of her father, of her cat who died five years ago from feline leukemia, of Amy, report cards from college (not very good) and even from high school (not much better). The wall used to have photos of Joshua, but she took them down, drew over his face, erasing him, leaving a black hole, and then put them back. And now her lottery ticket was scrap art, too.

And Amy, who had prided herself on reading only The New York Times, never read a rag like The Daily News, and because she hadn’t, she didn’t know what Lily’s grandmother knew and brought to Lily’s attention one Thursday when Lily was visiting.

Before she left, she knocked on Amy’s door, and when there was no answer she slightly opened it, saying “Ames?” But the bed was made, the red-heart, white hand-stitched quilt symmetrically spread out in all the corners.

Holding onto the door handle Lily looked around, and when she didn’t see anything to stop her gaze she closed the door behind her. She left Amy a note on her door. “Ames, are we still on for either The Mummy or The Matrix tomorrow? Call me at Grandma’s, let me know. Luv, Lil.”

She went to Barnes & Noble on Astor Place and bought June issues of Ladies Home Journal, Redbook, Cosmopolitan (her grandmother liked to keep abreast of what the “young people were up to”), and she also picked up copies of National Review, American Spectator, The Week, The Nation, and The Advocate. Her grandmother liked to know what everybody was up to. In her grandmother’s house the TV was always on, picture in picture, CNN on the small screen, C-Span on the big. Grandma didn’t like to listen to CNN, just liked to see their mouths move. When Congress was in session, Grandma sat in her one comfortable chair, her magazines around her, her glasses on, and watched and listened to every vote. “I want to know what your brother is up to.” When Congress was not in session, she was utterly lost and for weeks would putter around in the kitchen or clean obsessively, or drink bottomless cups of strong coffee while she read her news-magazines and occasionally watched C-Span for parliamentary news from Britain. To the question of what she had done with herself before C-Span, Grandma would reply, “I was not alive before C-Span.”

/>

She lived in Brooklyn on Warren Street, between Clinton and Court in an ill-kept brownstone marred further not by the disrepair of the front steps but by the bars on the windows. And not just on the street-level windows. Or just the parlor windows. Or the second floor windows, or the third. But all the windows. All windows in the house, four floors, front and back, were covered in iron bars. The stone façade on the building itself was crumbling but the iron bars were in pristine shape. Her grandmother, for reasons that were never made clear, had not ventured once out of her house—in six years. Not once.

Lily rang the bell.

“Who is it?” a voice barked after a minute.

“It’s me.”

“Me who?” Strident.

“Me, your granddaughter.”

Silence.

“Lily. Lily Quinn.” She paused. “I used to live with you. I come every Thursday.”

A few minutes later there was the noise of the vestibule door unlatching, of three locks unlocking, of the chain coming off, and then came the noise of the front door’s three dead-bolt locks unbolting, of a titanium sliding lock sliding, of another chain coming off, and finally of the front door being opened, just a notch, maybe eight inches, and a voice rushing through, “Come in, come in, don’t dawdle.”

Lily squeezed in through the opening, wondering if her grandmother would open the door wider if Lily herself were wider. Would she, for example, open the door wider for Amanda who’d had four kids?

Inside was cool and dark and smelled as if the place hadn’t been aired out in weeks. “Grandma, why don’t you open the windows? It’s stuffy.”

“It’s not Memorial Day, is it?” replied her grandmother, a white-haired, small woman, portly and of serious mien, who took the bags out of Lily’s hands and carried them briskly to the kitchen at the back of the house.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

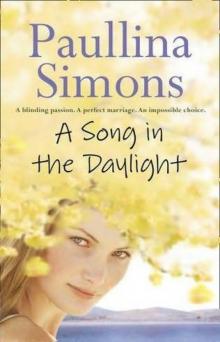

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)