- Home

- Paullina Simons

A Beggar's Kingdom Page 19

A Beggar's Kingdom Read online

Page 19

The rooms have a balcony and come fully furnished. Breakfast and supper are served downstairs in the dining room, and afternoon tea can be brought up to the rooms, “if the sire so desires.”

Hiding his two remaining gold coins in the feathers of the goosedown mattress, he drapes the cloak Miri had given him over his shoulders and heads to the apothecary.

∞

Julian returns to Seven Dials laden with ointments and a hot breakfast for Agatha. In the alleys behind the narrow houses where they pitch their buckets of waste and old water, the gloop runs through the streets, mixing and melting with mud, and steams up in the morning sun. He finds Agatha in her chair, watching the quiet but misty square.

“I didn’t recognize you in yer new clothes!” Agatha says, smiling happily. “Don’t you look smart.”

Julian suspects he’s still overdressed. If Miri can’t learn to trust him, he’ll have a bear of a time getting near her, he thinks, perching next to the lumbering and receptive Agatha as he serves her breakfast. This early in the morning, Seven Dials is empty. The business of the rookery has not yet begun. Agatha is up, she tells him, because she’s waiting for the parish priest to arrive with her daily relief. If she’s not up and about, the pastor knows she’s stayed up too late the night before doing things she’s not supposed to, and then she doesn’t get her allowance. “Consider this me job,” Agatha says to Julian, sunny as all that.

While the woman scarfs the bacon and bread with grateful gusto, Julian mixes coconut oil with frankincense and honey into a greasy salve. He cuts up a roll of gauze and folds it over itself several times, to thicken it. Dipping the cotton into the sticky potion, he sits on the ground by Agatha’s feet and rubs the salve into the lesions on her legs. He’s doing it for Miri. If anyone asks, that’s Julian’s answer to everything. He is doing it for the girl.

“So where’s your daughter today?” he asks Agatha in his most casual tone.

“Prob’ly sleeping. She works all night. We won’t see her till noon.”

Does Julian dare ask? “Doing what?”

“Oh, this and that,” Agatha replies, to confirm Julian’s worst fears. “I keep telling her, no one else works so hard, why should she? Julian, it’s nice of yer to help me, real nice.” The mother sits without protest and allows Julian, a young man she barely knows, to treat the sores on her legs. She is starved for a sympathetic ear, for a genuine human connection. While Julian tends to her, Agatha distracts him with the details of all the petty miseries that have plagued her since youth. She floods him with rambling tales about her life, the life of every person she’s ever met, and every small and grand injustice she has ever borne.

Julian learns that Lena, near St. Clement, sells apples as she waits for her parish relief and acts “holier than thou,” but everyone hates her because she’s had three bastard children by three different men and has been using the children to raise her relief to nearly “a full shilling a day!” which is unheard of. Now as punishment, Lena is apprenticed to the parish and must sell pamphlets about Judgment Day for half a penny each. “Work is part of her penance,” Agatha says. “As work often is. But does she sell them? No. She gives Miri a farthing to do it. And Miri does it! What does my poor Miri have to atone for? She’s a perfect child. I’d rather collect my lousy threepence and not have to be put through the wringer of a fake job, don’t you agree?”

Julian learns that Miri is twenty-three. Mortimer, the old man of their merry band, is twenty-seven, Jasper is twenty, and so is Monk.

“Monk is twenty?” That’s shocking.

“I agree, his feeble-mindedness makes him seem young,” says Agatha. “His brother Fulko is Miri’s age. You want to talk about feeble-minded. That boy doesn’t have the sense God gave a gnat. He just charms and tricks his way out of things. Which is prob’ly how he got Miri to fall for him. But he ain’t charming his way out of a killing.”

Miri fell for Fulko? Julian mentions that she and Monk are raising money to get Fulko’s sentence commuted.

“Oh, sure,” Agatha says dryly. “They been raising this money since Christmas. I do hope Fulko is not holding his breath. And commuted to what exactly, transportation? Blimey. It’s a slow death, also he don’t want to leave the country. I didn’t. You look surprised. But them bastards threatened me with transportation, too.”

“Transportation to where?”

“Where d’you think? Those damn penal colonies, the Americas. Miri was one at the time. Can you imagine? A littl’un on a boat for months! In the middle of the open sea! I told them I’d rather hang at Tyburn. They said that could be arranged. I got out of it by pleading the belly.”

“Pleading the what?”

“Pleading the belly. You know.” Agatha points to her bulging stomach. “Showed ’em I was preggers so they’d go easy on me. Worked like a charm. Usually does. The baby didn’t make it, but she served her purpose, got her mum out of transportation and sprung early from Bridewell.”

“Where was Miri?”

“The orphanage, where else? I don’t like to brag about it, but truth is, I’ve had some trouble with the law meself. Me husband was no good, and I had to make a living somehow. I was ruined by marriage, Julian,” Agatha says, as if divulging great confidences. “I had to steal to keep Miri from starving. I admit to some occasional disorderly behavior. Some begging. But you beg too often, they flog you till your back’s bloody, you beg after that, they hang you. Well, they didn’t hang me, but those fuckers did send me to Bridewell, that unholy pit of sexual corruption, and took me Miri away. They called me a common nightwalker!” Years later, Agatha still broils from the insult. “I wasn’t no common nightwalker! I wasn’t like that Priscilla over there, putting on airs, do you see her? Like she’s goin’ to catch a customer this early in the morning. Oh, look! There’s my friend, Repentance Hedges. Repentance, come here, meet Julian! When did you get out, girl?” And to Julian, Agatha mutters from the side of her mouth, “Repentance is fifty-two and spent thirty years in and out of prison. The parish keeps collecting for her damn kids, slothful and soused to the one. Monk and Fulko are two of them. I keep reminding Miri, Repentance will soon be her mother by law. If that don’t get you to change your mind about marrying a no-good nobody, nothing will. Just look at that woman!” Agatha speaks from the bottomless pool of her indignation. “Repentance’s been engaged in lewd behavior for as long as I’ve known her. But nowadays she has a hard time attracting customers, not being in the first blush of youth and all. Repentance, how are you? Yer looking good, girl.” Agatha clicks her tongue in disapproval.

Repentance approaches, her old striped petticoat dragging on the ground. “Who’s your most kind friend, Agatha?” She smiles invitingly at Julian.

Agatha stops smiling. “Move along, the kind man ain’t got no pennies for you.”

Repentance continues to smile. She looks older than fifty-two. It doesn’t help that some of her teeth are missing. Her skin is ashen white, a sign of mercury poisoning. Mercury is taken to treat syphilis. “He looks like he’s got money. He’s wearing money. Look at his felt hat, Agatha. And his cufflinks! Hello, good sir, would you like a little bit of company? Not a lot, just ever so little.”

“That’s where all my money is,” Julian says, rising to his feet. “In my felt hat and my cufflinks.”

“I don’t need much,” Repentance says. “Tuppence for a quick shag will do. Standing up, just over there.”

As politely as he is able, Julian declines.

Repentance bristles. “You going to insult a woman’s honor by refusing to occupy her?”

Julian is saved by Pastor Wyatt, who arrives on the scene just in time with relief and prayers. Repentance vanishes. Wyatt is a goodly and serious priest, bald with small penetrating eyes. After examining the medicated gauze on Agatha’s legs and laying a sign of the cross on both her and Julian, he places tuppence into her fist. “If you listen to the Lord, Agatha, he will heal you. Stay away from the drink, and everything else

will be made better.”

After the pastor departs, Agatha smiles a gap-toothed grin at Julian. She appears in better spirits with money in her hand. “Do you know what I could use right now? A dram of that very good rum Elvar is selling on the corner of Queen Street. It’s exactly a penny. Would you be a dear?” She tries to stuff the coin into Julian’s fist, but because he is ambulatory and she’s not, she can’t reach him.

“Agatha,” Julian says, “like the pastor, I must advise you against rum. It will interact poorly with the ointment on your legs. Rum will make you vomit, is that what you want? It’ll make you go off bacon.”

“Go off bacon? Damnation!” Agatha loves her rashers. But she also loves her gin. Gin and bacon are her two great loves. Reprieve comes in the shape of avian Hazel, who emerges in the square, sidestepping gingerly as if she’s just learned to walk. When she sees her old friend, Agatha forgets about rum for a moment. “Hazel, is that you?” she shouts. “What are you doing up and about?”

Julian praises Hazel for following his advice and getting some fresh air. He gives the woman the chickweed he’s bought for her. “Just chew the leaves, Hazel. Every day. And put some on your legs. You’ll feel better in no time.”

“This nice man told me I have a wraith deficiency!” Hazel informs Agatha as if Julian has given her a diploma.

“Yeah? Look what he gave me. Bandages!” Agatha shows Hazel the gauze around her injured legs. “He told me I might have impetigo!”

“Might? I have a wraith deficiency!”

As they squabble, Julian takes the opportunity to slip away. Reeling from his morning with Agatha, he stumbles through the rookery, searching for Miri. The girl could’ve sailed to America with her mother when she was a baby. She could’ve gotten out.

Miri was such a good girl when she was little, Julian keeps hearing Agatha say. Agatha would visit her at the orphanage from time to time. “She’d put on these little acts. She’d get up on a box and perform silly things she’d heard on the streets.” Agatha’s bloated face dissolved in the memory. “With her elbows out and hands on her hips, she’d yell, Akimbo, akimbo! To this day I don’t know what it meant.”

“It means elbows out and hands on your hips,” Julian said.

“She’d recite a little parable called the Lump of Ice and Crystal. Begotten in a muddy puddle, a lump of ice resented the crystal’s clarity, so it started praying to the sun. The sun heard the ice’s prayer and began to shine.” Agatha smiled, her eyes glistening. “I remember it like it was yesterday. She was such a good happy girl, never envious, never wanting more than she had. Always smiling. You wouldn’t know it now from looking at her, but she was beautiful, too.”

Julian knows it. A good happy girl always smiling.

“They throwed Miri out of the orphanage when she was eleven. She’d locked a constable in one of the rooms and beat the daylights out of him with his own stick. Damn near killed him. Said he tried to touch her. How she escaped death for that, I’ll never know.”

Julian searches for Miri among the wretched.

Everything could’ve been completely different.

He finds her off Long Acre, in one of the narrow alleys between two tenements. She’s waiting her turn in line for the spout valve. For a few minutes each morning, the city turns on the water, to wash the refuse from the streets into the sewer grates.

It’s Miri’s turn at the open valve. Julian watches her as she, bent at the waist as if taking a consecrating bow to the standpipe, runs her hands under the water and washes her face and neck. She gargles. She is quick, efficient, impassive. Before she straightens, she notices a spot on her old shoes. She sticks the shoe under the water until the spot comes off. Then she straightens out, turns, and sees Julian.

His pity for her, his desperation, his bitter tenderness, his excruciating helplessness must be so plain on his tormented face that when Miri catches his expression, she reacts like anyone half-sane would. Realizing that there are things in the universe she doesn’t understand and doesn’t want to, and for which there is no good or rational explanation, Miri flees. She runs from him as fast as her old clean shoes will carry her.

17

Midsummer Night’s Dream

TWO DAYS LATER, JULIAN IS HAVING A LATE DRINK AT THE Lamb and Flag near Covent Garden, drowning his wordless angst in a tankard of ale, maybe three. He likes the Lamb and Flag. In the late afternoons they host bare-knuckle fights in the back garden, the rookery version of happy hour. It’s quite entertaining. Brutal but entertaining.

Tonight, there’s laughter in the pub garden, raucous men getting drunk, nearly coming to blows. He hears a woman’s voice behind him. “Hey, handsome,” the voice purrs. “Would ya like some company?”

Julian spins around.

It’s Miri.

It’s not the Miri he knows, the waif of Neal’s Yard. It’s a different Miri. She stands close to him in a blonde wig, wearing a frozen come-hither smile and a starched white dress sewn with blue flowers. The dress has a swing to it, a hula-hoop crinoline, a tight corset, and a low neckline that exposes the tops of her young white breasts nearly to the nipples, the breasts in full pushed-up display to entice what she had clearly hoped was a different man drinking alone, looking for company. Over her blonde wig is a white bonnet. Silk ribbons hold up her fake yellow hair. Her face is scrubbed, there’s red on her cheeks and lips, and her eyes are lined in black crayon. The smile that wasn’t meant for him is flirty and sexy. She’s got an air of filthy erotic mystery to her, and erotic history. Julian is Miri’s accidental mark tonight.

“Hello, Miri,” he says.

Never has Julian wiped a smile faster off a woman’s face.

Irritated and embarrassed, she backs away, but not far enough. The two of them are hemmed in on a dark warm night in Covent Garden.

“What are you selling tonight?” Julian asks. “War, or something else?”

“Leave me alone.”

“But you just asked if I’d like some company,” Julian says, standing up. “I do—very much. And I’m willing to pay handsomely for it. What’s your usual rate? I’ll triple it.”

“Leave me alone.”

“A shilling, Miri? A guinea? A quid?”

She whirls from him and insinuates herself beside another inebriated dupe. A minute later she leaves on the mark’s arm. Julian follows, hoping he is sober enough not to pick a fight with the chap until he sees where this is going. With all deliberate speed, Miri lures the gentleman into St. Giles. The guy needs to be pretty desperate to follow her there, Julian thinks, pacing them; either that, or desperately ignorant. Kind of like him. The idiot doesn’t balk at his surroundings, not even when she leads him through Seven Dials. Nothing tips him off. Julian can hear Miri purring to the man in her purry voice. She flatters and cajoles him into an alley, down the stairs, and into the St. Giles dining hall in the cellar. She promises the mark some beer, and even dancing. “We’re not Puritans,” Miri tells him. “We have music. We know how to have fun.”

The man wraps his drunken arm around her delicate hip. “All in good time,” she says, easing out of his hands. “Why don’t we start with a meal and some songs, and we’ll see where we end up.”

Oh, the royal treatment the legless gentleman gets in the crowded rookery mess hall. Julian finds a spot in the corner and silently watches. The hall is a long room with a burning fireplace, a sink, a water tap, and a half-naked woman playing a fiddle. Only one of her breasts is out. Like a king, Miri’s guest of honor is placed at the head of a long table and stuffed with food and lubed with drink. The rookery table is laden. It’s a feast in a castle. There’s steak with onions, mutton pork chops, fried potatoes, sausage, cheese, and dessert of pudding pie, home-brewed gin, and a snuff of tobacco. Young topless women dance on his table. Though keeping most of her clothes on, Miri is one of those women. Julian watches her two-step and spin, hooking her arms with another girl, clicking her stacked heels, flushed and sweating, her bodice unbuttoned, her h

alf-covered breasts bouncing up and down. If he didn’t know it was all an elaborate con, from the expression on her face he’d think she was happy.

And then the mark passes out in his plate.

The topless woman continues to play the fiddle, but the dancing on the table ceases cold. Miri jumps down. Mortimer and Monk strip the man of everything not attached to his skin. They clean him like a fish. They take his silk purse, his leather billfold, his coat, his boots, his hat. They take all his clothes and his cloak (so that’s where Miri gets the clothes she gave to Julian). The boys are good enough to leave the chap his linen drawers. Mortimer motions Julian over for an assist. He and Mortimer grab the man by the arms and legs, carry him upstairs and outside, throw him into a handcart—like Lord Fabian, but alive, so a modest improvement—and wheel him back to Covent Garden, dumping him in an alley next to the long-closed Lamb and Flag. It’s four in the morning.

“Well done, mate,” Mortimer says to Julian as they head back. “I have a hard time loading them up and carting them by myself. Monk’s no help. And me brother is usually, um, disabled well before midnight. I used to do this with Fulko, but you know…” Mortimer trails off, but he might as well draw a noose around the ellipsis.

“How often do you do this?” Julian asks.

“Most nights. Except Sundays. Too quiet. Especially Easter Sunday, it’s dead out here at Easter. But Christmas is very good. Everybody’s pockets are full at Christmas. That’s when Fulko got caught.”

“Miri does this every night?” Julian is upset. Her time grows shorter with every new thing he learns about her.

“Yes, but what’s it to you? She wants to. No one’s forcing her. I tell her to be more careful, but she don’t listen to nobody. Everyone helps out. Miri, Flora, Hazel when she could walk, our mother. Miri’s mother. We use different women, go to different pubs, mark different men. You don’t want to accidentally grab a man you’ve already fleeced, but it rarely happens.” Mortimer snickers. “Usually they’re too ashamed to return to the same pub.” He’s quite talkative tonight, as if he and Julian are partners in crime, as if Julian can be trusted.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

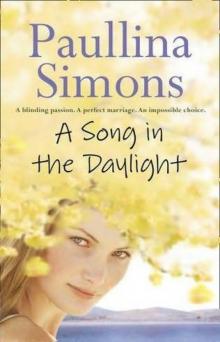

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)