- Home

- Paullina Simons

Inexpressible Island Page 15

Inexpressible Island Read online

Page 15

While Shona sings, a gleaming Mia, dressed in a white sheet and carrying the white towel bouquet, glides through the rows of people, taking her time, smiling left and right. She looks like an otherworldly specter. She said she wanted to walk down the aisle, and she’s savoring the opportunity.

Julian gives her his hand to help her up. She balances out the rocky door with her weight as they bob and sway toward each other as if on deck of a ship.

“Ever since they met, on top of this rickety door masquerading as a stage, Bride and Johnny have had quite a tumultuous time together,” Peter Roberts says. “Love being a majestic bird, they fell in love deep inside a cave, while outside and above, they’ve been baptized by fire. Tonight, they have returned to the cave to unite themselves in holy matrimony, because they know it is in the cave that the life of the world began, the old world and the new. They will be together until death do them part,” Robbie says.

“Not even then,” whispers Julian and Mia says, “What?”

“To commemorate this joyous occasion, they’re going to speak at their own nuptials. Yes, ladies and gentlemen, you heard correctly. Who goest first?”

“I do,” Mia says. “Every love affair should begin and end with a joke or a poem. I have the joke. And Johnny Blaze has the poem.” She stands half facing him, half facing the audience.

“What is the Ideal Man?” says Mia. “The Ideal Man should lavishly praise us for all the qualities he knows we haven’t got! But he should be quite pitiless in reproaching us for any virtues we never cared to have in the first place. The Ideal Man should worship us when we are alone.” Coquettishly raising her brows, she bares her white neck to Julian, which he obliges by kissing. The audience hoots and whistles. After a few soaked moments, a flushed Mia steps away, clearing the thickness from her throat. “Worship us, yes,” she says, “yet he should be always ready to have a perfectly terrible scene—in public or private—whenever we want one. And after a dreadful week of fighting he should, if necessary, admit that he has been entirely in the wrong, and then be willing to do it all over again—from the beginning, with variations. Are you that Ideal Man, Johnny Blaze?”

“Without a doubt,” Julian replies.

Chortling with joy, she offers him her hand to kiss. “O, Johnny, do you have a poem to make them cry?”

“I do.” He takes a breath. “What is your substance, whereof are you made,” he says, taking both her hands in his, “that millions of strange shadows on you tend? Since everyone has, every one, one shade, and you, but one, can every shadow lend. Speak of the spring and autumn of the year, the spring does shadow of your beauty show, the autumn as your bounty does appear—in you is every shape I know. In all external grace you have some part, but you like none, none you, for constant heart.” Julian’s eye throbs. Pressing his palm into his brow, he looks away from her emotional face and into the clapping audience.

“We will now recite for you a short dialogue from George Bernard Shaw,” Mia says. “Are you ready?”

“Always, Ghost Bride.”

“On your knees. If you can,” she adds, a gentle reference to his torn-up calf.

He descends to his knees, wincing slightly. Her soft hand remains in his.

“A man cannot die for just a story and a dream,” Mia says. “I know that now. I’ve been standing here with death coming nearer and nearer, and reality coming realer and realer, and all my stories and all my dreams are quickly fading away into nothing.”

“Are you going to die for nothing, then?” Julian says.

“No,” says Mia. “I have no doubt that if I must die, I will die for something bigger than dreams or stories.”

“Like what, Ghost Bride?”

“I do not know,” Mia replies. “If it were for anything small enough to know, it would be too small to die for. What about you, Johnny Blaze?” She gazes down at him. “Will you be ready to die for something other than a dream or a story?”

“No,” Julian says. “You are my dream. You are my story. I will die for you.” He gazes up at her. “I am your soldier, and you are my country. But first, will you please come down to earth, Ghost Bride? Come down from your cloud of dandelion, and marry me in the asphodel, please, will you marry me in London pride?”

She bends to him, he lifts his head to her, and they kiss.

They kiss and kiss.

“Well done,” Mia whispers into his ear, embracing him. “They’re all bloody weeping.”

“So I win, right?” With effort, he rises to his feet.

Robbie takes the job of fake minister as seriously as he takes learning French. He stands pin straight and instructs them to put the rings on their fingers. Then he speaks in deep and sonorous British. “Ghost Bride and Johnny Blaze, we sit around the fire and tell each other stories in order to live. This is the start of your story.” (If only. Julian squeezes Mia’s hand to keep his own from trembling.) “You are here to make a new life. And your marriage is not a declaration, just once, at the beginning. As a boxer, Johnny, you don’t say, I fought one fight and thus I’m always winning. Your marriage is a choice every day. You choose to love one another, to honor your friends, to play it for a new crowd. Your life is your ever-changing stage. Bring it every night, and leave nothing in the wings. Do not say, once upon a time in December, I was in a war wedding. Say it eight times a week, fifty-two weeks a year. To be faithful, you must first have faith—in the whole dang thing. That’s what love is. So go forth, and live your story, Ghost Bride and Johnny Blaze.”

After it’s over, Mia takes off her ring and returns it to Julian. She asks if she can keep the beret. Why not, he says. He lets her have it. After all, he is not going to need it anymore.

“Are you sure you don’t want to keep the ring, too?” he asks.

She laughs as if he is the funniest man in the Underground.

For his performance, Robbie gets more handshakes and compliments than either the fake bride or the fake groom. Two days later, a red double-decker bus gets caught in a bomb blast and stands motionless in the middle of Cannon Street with its passengers dead in their seats. One of those passengers is Peter Roberts, who was on his way to Victoria to take a train to Sussex to be reunited with his wife. He is found upright, open eyes staring ahead, the bowtie under his chin perfectly straight.

18

Deepest Shelter in Town

AFTER THEY LOSE ROBBIE, WILD SAYS TO HELL WITH IT. “Swedish, I will never forgive you and Folgate for getting fake married without me, but I’m not missing your wedding reception at the Savoy because of the fucking Krauts. Let’s go. No Oxford Street, no new clothes. Men, clean the damn suits you’ve got, ladies, shine your shoes, a little lipstick, a little perfume. Tomorrow is Friday. A great day for a celebration. Things can only improve.”

Mia puts on her Florence Desmond black velvet dress with red trim, in which she sang “The Deepest Shelter in Town.” She has two other dresses, she says, but she liked the way Julian ogled her when she danced in that one. They clean their faces, change their dressings, shave, and brush their hair. Mia takes her arm out of the sling. Julian tries not to limp. His brow is healing, the swelling has gone down, the black eye is yellow and purple. Phil was supposed to take out the stitches, but then he died. Julian pulls them out himself, probably a few days too soon. Duncan tries to walk like his back isn’t killing him. They all do their best to look worthy of the Savoy dining room. Unfortunately Nick has gone back to Dagenham; he heard that the Ford plant was reopening.

Julian makes a dining reservation for nine of them: himself, Mia, Wild, Liz, Duncan, Shona, Sheila and Kate, and Frankie. It is an understatement to say that the three boys are delighted to be outnumbered by the six girls. “This way, ’tis heaven,” Duncan says.

“Imagine the hell if ’tis was the other way,” Wild says. Liz does not look thrilled with the current arrangement. She would prefer Duncan take four women on himself so she could have Wild all to herself. By Duncan’s expression, that’s what he wishes for al

so. “And technically, Swedish is taken up by Folgate,” Wild adds, “this being their fake wedding reception and all, so it’s even better for us, Dunk. Two real men against five fine women.”

“I’m not a real man?” says Julian.

“And why only technically taken up?” Mia says. “You think my fake husband is about to bolt now that he spies the bounty out there?” She takes Julian’s arm as they enter the Savoy, like they’re a gentleman and a lady, or maybe a husband and wife.

The porters hold open the heavy doors, and in their lounge suits and bowler hats and dresses, the Ten Bells stroll in as if they belong at a place like the Savoy. No one looks twice at their stitched-up and bandaged faces.

A concierge approaches them to ask if they know where they’re going.

“Tell him, Mia,” Julian says, “tell him, do any of us really know where we’re going, C.J.?”

“How do you know the concierge’s name?” Mia whispers.

“To the Grill,” Julian tells the man. He’s eaten there a few times. Many times, he and Ashton had gone to the art-deco American Bar for drinks. They’d gone to the Grill with Riley for Julian’s birthday in March, and for Ashton’s in August. Riley loved the place. And later on, so did Zakiyyah. Julian had even taken Devi and Ava there once, though Devi partook of the French-English cuisine like it was rookery gruel.

“Very well, sir,” the concierge says. “But you’re headed in the wrong direction. The Grill is not to the left of the lobby. That’s where our jewelry store is. The Grill is at the back of the hotel, overlooking the Thames.” He coughs. “Though, of course, no river view tonight. The curtains are drawn.”

“Of course,” Julian says. “And thank you.” He forgot the hotel had been renovated recently and the restaurants rearranged.

As they walk through the reception hall, Wild asks Julian if he’s still thinking of getting a room after dinner.

“Indubitably,” Julian replies. “After all, it’s our wedding night.”

Mia rolls her eyes. “He’s kidding. It’s our fake wedding night.”

“What about the rest of us?” Wild asks.

“You’re definitely not going to be in the room with us,” says Julian.

“He’s kidding.” Mia shakes her head.

“I’ll get you your own room,” Julian says to Wild.

Duncan and Wild look doubtful. “Are you sure you have enough money for such an extravaganza, Jules?” asks Duncan.

“I hope to soon be too drunk to care, so yes.”

They are placed at a large round table in the middle of the dining room underneath a crystal chandelier. Everyone tries to contain their glee as the menus are brought. They order the Savoy specialty—Pink Gin cocktails—discover they are teeth-rattlingly strong, and gasp at the prices on the menu.

“No one eat a thing,” says Duncan. “Not even a piece of bread. Or Jules won’t be able to afford the rooms he’s been promising. What would you rather have, ladies, caviar or a bath with me? It’s either steak or Duncan, girls,” he adds as a variation of the Minister of Food’s justification for the rationing at restaurants: “It’s either steak or ships, citizens of London.”

“Most definitely steak, Duncan,” Kate says.

To calm Duncan down, Julian slaps a twenty-pound note on the table. “Dunk, eat, drink, be merry, don’t worry about a thing.”

Duncan relaxes. After two Pink Gins, everyone relaxes. Plymouth gin, a dash or two of angostura bitters and a splash of soda, though for the second one, Julian asks the barman to add some tonic water, or they’ll all be under the table by the time the main course is served.

“Chaps,” Mia says, “did you know that the Savoy Hotel and Theatre, and my favorite Palace Theatre on Cambridge Circus, were all built by the same man?”

“Richard D’Oyly Carte, right?” says Julian with a twinkle. “With his profits from The Pirates of Penzance.” Julian smiles as he recalls the depth of his long ago bedazzlement high in the ancient mountains of Santa Monica when she was still Josephine, waxing poetic about a man who loved a woman so much he built her a theatre.

But tonight it is Mia who looks bedazzled. “I still don’t know how you know that,” she says, “but yes, he built the Palace as a labour of love, but my point is that it was art that made real life possible—that imaginary, make-believe things came first, and they helped build real historic places.”

“And please real women,” Julian adds.

Mia becomes flustered by his expression, and he by hers.

“We heard the Savoy rooms have steam heat and soundproof walls and windows,” Shona says, refocusing the conversation on where it needs to be.

“Do you need soundproof windows, dear Shona?” Duncan asks, grinning like a clown.

“I’m done with you, Duncan,” she says in the liquid tone of someone for whom the opposite is true.

They order grilled chicken and roast potatoes, foie gras and caviar, steak, bouillabaisse, and bangers and mash. They eat family style, a little of everything. It’s all delicious.

“Eating out is a morale booster,” Wild says.

“So is sex,” says Duncan.

“Duncan!” the girls yell.

“There’s help for people like you, Duncan,” Wild says, swallowing a tablespoon of caviar without any bread or butter. “In Piccadilly. Sure, Eros has been evacuated, but even in the blackout, the Piccadilly Commandos walk back and forth in the darkness, carrying torches so you can easily find them. Go, Dunk. They’re waiting for you. But remember, don’t ask for any extra. No use getting fancy. There’s a war on, as the council keeps telling us. Luxuries in sex are unpatriotic.”

“Everything is either unpatriotic or compulsory,” Duncan says. “What we eat. How much we eat. What we wear. What we wash our hair with. How we file our war damage claims, where we sleep. Why can’t they make sex patriotic and compulsory? Like every day, to do your part for the war effort, you must have a minimum of this. You can have more. But this must be the absolute minimum.”

“Duncan,” says Frankie, “is it possible for you to talk about anything else? Have you got anything else in that head of yours?”

“Trust me, Frankie,” Duncan says, “it’s not my head I’m thinking with. Besides, these are modern times. You girls keep saying you want to work like men, dress like men, live like men. Well, this is how men talk. Get used to it. This is what sexual equality means.”

“Sexual equality, you don’t say,” Liz intones slowly—nearly the first thing she has said all evening. “Sexual equality would be if after each act of love, both parties were uncertain as to which of them would conceive the child. Now that would be true equality. Until such time, shut up, Duncan, and act like a gentleman. Look, Julian and Wild are behaving themselves.” Her voice melts when she speaks the name Wild, though she doesn’t dare raise her eyes.

“Wild has never behaved himself in his life, Lizzie,” Duncan says. “And have you forgotten how Julian mauled another man’s girl the second he laid eyes on her?”

“Excuse me,” Julian says. “I did not maul. Right, Mia?”

“Why ever not?” Mia says, raising her glass. “To Finch!” They have another boisterous Pink Gin round.

They’ve decided that Pink Gin is supremely patriotic. Wild raises his glass and says it’s his privilege to do his small bit to hold up Hitler’s plans. He downs the cocktail in one gulp. Wild can really hold his liquor.

“Yes, it’s miserable now,” Julian says, offering words of encouragement, “but it will get better, I promise you.”

“It’s not so miserable now.” Duncan smiles, looking around the glorious room, happily smoking.

“Sure, Swedish, eventually it’ll get better,” Wild says. “Either the Germans will run out of planes, or we’ll run out of people.”

“Oh, we’ll definitely run out of people first,” Duncan says. “How can we not? No one’s shagging, no one’s bonking. Truly the world is about to come to an end.”

“The world i

s coming to an end,” Shona says. “Did you hear that Peckham was destroyed two days ago?”

“Do you know why?” says Duncan. “Because everything is worse south of the river, even the bombing.”

“Oh, I don’t wish that even on poor Peckham.”

“Let’s pray for Peckham.”

“Yes, let’s raise a glass to Peckham.”

They drink again.

“My auntie lived next to a paint factory,” Shona tells Duncan, leaning into him. The drunker those two get, the chummier they become. “You can imagine how that burned, all those chemicals, all that turpentine. Oh, it burned magnificently, in all the colors of the rainbow. If you weren’t so terrified, you had to admit it was very beautiful.”

“But then you died from the poison fumes,” says Wild.

“Yeah, but while you lived you saw beauty, not a bloody tunnel in a bloody tube station.”

“The Bank is home, Shona,” Wild says solemnly. “Don’t judge. Everything can’t be the Savoy. We need the contrast.”

“Between the ditch and the Savoy?” Shona smirks.

“Yes,” says Wild. “The ditch became Tower Street became Eastcheap became Cannon Street became Ludgate Hill became Fleet Street became the Strand became the Mall became Buckingham Palace.”

“Wild, you’re a boy after my own heart,” Julian says, raising his glass. “But speaking of Buckingham Palace, I don’t know why the King and Queen have not evacuated. They’d be so much safer in Canada.” In 1666, Charles II fled during the Black Plague, as Baroness Tilly had informed him. What’s happening now is worse than the plague.

“How would it look, the King said, if we left our people and ran for the hills?” says Mia. “What kind of an example would that set? The King’s exact words were: How can we look the East End in the face?” She shrugs. “Good old George needn’t have worried. Soon there’ll be no face left in the East End to look into.”

“At least Buckingham Palace hasn’t been hit,” Julian says.

The Summer Garden

The Summer Garden Six Days in Leningrad

Six Days in Leningrad Bellagrand

Bellagrand Tatiana and Alexander

Tatiana and Alexander Road to Paradise

Road to Paradise The Bronze Horseman

The Bronze Horseman Eleven Hours

Eleven Hours Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love

Tatiana's Table: Tatiana and Alexander's Life of Food and Love The Girl in Times Square

The Girl in Times Square The Tiger Catcher

The Tiger Catcher Lone Star

Lone Star Children of Liberty

Children of Liberty A Beggar's Kingdom

A Beggar's Kingdom Inexpressible Island

Inexpressible Island Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel

Tatiana and Alexander: A Novel Tatiana's Table

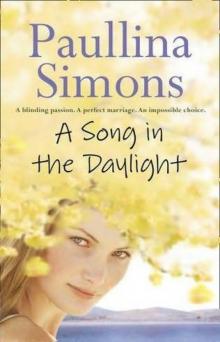

Tatiana's Table A Song in the Daylight (2009)

A Song in the Daylight (2009)